Making Waves

A Short History of Feminism

Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

Last Sunday, I sent out a newsletter discussing the term ‘Protofeminism’ and looking at the women writers who espoused this sentiment. As discussed, the proto feminists are described as anticipating feminism before the term was officially used, and often wrote about the issues affecting women within their fiction. This was seen to have anticipated the later Women’s Movement.

Over the next few weeks, I plan to look at some of the outstanding voices in feminist thought and writing, as well as some of the different issues and splinters of the Women’s Movement, such as Black feminism and Intersectionality. But I thought it might be useful first to examine what is often termed the ‘Waves’ of feminism. These can sometimes get confused, and of course, many of the issues and so-called waves cross and re-cross as women have fought (and continue to fight) for gender equality.*

First-Wave Feminism: 1840s to 1920s

The term first-wave feminism actually refers to the first political movement supporting rights for women in the West between roughly the late 1840s to the 1920s. It does not refer to the thoughts women had on feminist ideas earlier than this period, though of course many did, as we saw in my protofeminist piece. First-wave feminism was primarily involved in achieving political equality for women in the West, culminating in both the suffragette and suffragist movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.1

First-wave feminism involved marches, lectures, and protests, as women fought for equal voting rights with men. Many faced arrest for their efforts, and violent protests were carried out by members of the suffragette movement in the UK, formed and run by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, Christabel and Adela. Suffragettes often faced ridicule and imprisonment. Famously, suffragette Emily Davison was killed when she threw herself under the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913, becoming a martyr to the cause.

In the US, the first-wave is often reported to have started with the Seneca Falls convention in New York of 1848, where almost 200 women met to discuss the rights of women. Twelve resolutions were called at this meeting, demanding specific equal rights for women, including the right to vote.

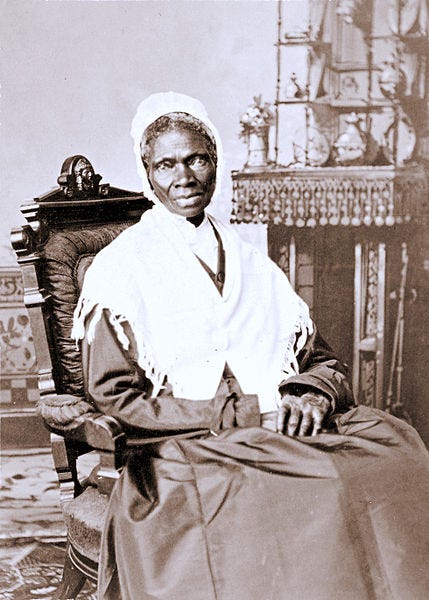

The convention had been organised by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, both abolitionists who had been barred from the floor of the 1940 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where no women were allowed. The suffrage movement in the US at this time became integrated with the abolitionist movement, with women of colour such as Sojourner Truth becoming major forces within the movement, demanding not just women’s suffrage but universal suffrage.

Despite this, the movement led by Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton established itself as a movement specifically for white women, spurred on by the fifteenth amendment to the constitution of the US in 1870 which granted the right to vote to Black men. Some of the white female members of the movement saw it as an outrage that former slaves gained the vote before white women did. Black women were barred from some demonstrations or forced to walk behind white women, showing a divide that would ripple through the women’s movement for decades to come. I shall explore the divides in the feminist movement and look at the leading voices in the Black feminist movement in future newsletters.

The women’s movement during this first wave sought not only for the vote but for equal opportunities in employment, education, and property rights. This further developed into the radical area of reproductive rights, with the opening of the first birth control clinic in the US in 1916 by Margaret Sanger, flagrantly violating the New York state law which forbade the issue of contraception. She later established the clinic Planned Parenthood. In the UK, Marie Stopes opened the first birth control clinic in London in 1921.

Women were eventually awarded the vote in 1920 in the US when the nineteenth Amendment was passed, though it remained difficult in practice for Black women to vote, particularly in the South. In Britain, meanwhile, suffrage was achieved for women over 30 who owned property in 1918, with full suffrage on the same terms as men for everyone over the age of 21 in 1928.

Second-Wave Feminism: 1960s to 1980s

It is often cited that second-wave feminism began with the issue of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, which was published in 1963, though the earlier Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir (1949), amongst other prominent feminist thinkers, would later be seen as influencing this second wave.

Friedan’s book brought up the issue of “the problem that has no name”, referencing the systemic sexism ingrained within society which told women that their place was in the home and that their unhappiness was due to their own brokenness. She argued that this wasn’t the women’s fault but the fault of a culture that did not encourage them to live up to their creative and intellectual potentials: they had a right to be unhappy as they were being ripped off by an unjust system.

Sometimes stated as not being a revolutionary text in its ideas and thinking, Friedan’s book was nonetheless revolutionary in its reach. Crucially, it made its way into the hands of the middle-class white housewives it was aimed at, who passed it around their friends. Over three million readers read Friedan’s book and realised their anger, pushing a new wave of feminism to emerge: this time, for social equality.

“The personal is the political” became the mantra of the second-wave feminists, arguing for better access to things like childcare, abortion rights, reproductive rights, and domestic labour. Landmark laws were passed by the Supreme Court in the US during this wave in areas such as the right for both married and unmarried women access to birth control, The Equal Pay Act of 1963, and the Roe-v-Wade case in 1973, which guaranteed women’s reproductive rights.

The second-wave feminists worked on women’s rights to own a credit card in their own name, apply for mortgages, outlaw marital rape, and supported the work of shelters for women leaving abusive relationships, as well as sexual harassment in the workplace.

It also saw it as essential to change the way society saw women, looking to extinguish the sexism endemic in society, and showing that women went far beyond domestic and decorative qualities.

Racism still proliferated the movement however; Friedan’s book was directly aimed at white, straight, middle-class women. Gaining the right to work outside the home for married women was a moot point for many Black women in the US, who already did so. Many influential voices, writers, and campaigners came out of this era of feminism which I shall examine in later newsletters, including the work of Black pioneer Dorothy Pitman Hughes, and the work of Gloria Steneim, who together fought for a unifying feminist movement.

British feminists meanwhile, influenced by their American counterparts, followed suit in their demands for reproductive and financial rights. This movement was known as Women’s Liberation, and saw many women leaving unhappy marriages and seeking sexual and financial freedom from men. Books such as The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer became popular in the movement in the 1970s, challenging women’s roles within society. Greer, an outspoken Australian in the UK, argued for liberation rather than equality, seeing the family institution as preventing women from reaching their full potential.

Third and Fourth-Wave Feminism: 1990s to Present

As conservatism spread in the 1980s with both the Reagan administration and the Thatcher government, a re-establishing of family values once again took hold and the feminist movement began to suffer from bad press. Feminists were often seen as men-hating lesbians who didn’t shave and hated anyone having any fun. Some younger women distanced themselves from the image of a feminist, seeing them portrayed as angry, bitter, lonely women. Sadly, that image took hold, as the second-wave feminism that had seemed so liberating began to lose momentum.

Many people dispute when - or if - third-wave feminism started, or if indeed it is still continuing. There is also speculation of whether we are entering a fourth wave.

Much of 1990s feminism fought workplace discrimination, looking to extinguish sexual harassment, promote women to higher positions of power, aiming to get more women Board members, and putting trans rights on the agenda, which became a fundamental part of Intersectional feminism.

1990s feminism was also influenced by the rise of the riot grrrls; girl bands whose lyrics showed their anger at a society which portrayed them as weak and stupid. Unlike the second-wave feminists, who downgraded the word ‘girl’ in favour of ‘women’, the riot grrrls embraced their girliness, encouraging the wearing of makeup and high heels, often shunned by their 1960s and 70s counterparts. This was, in part, a rejection of the 1980s views of second-wave feminists as unfeminine and unattractive, as well as the belief that rejection of their femininity was in itself a misogynistic belief: they wanted it known that being feminine was no less valuable than being masculine or androgynous. These feminists wanted to dress up and have a good time, doing things that brought them pleasure, without asking for permission.

But this area lacked something of the cultural momentum of the earlier waves of feminism, until the arrival of the #metoo movement, which many have seen as the catalyst for what some are referencing as fourth-wave feminism. Women’s marches again became centre stage as the Harvey Weinstein case and others came to the fore.

Much of the spread of messages around #metoo and feminist activism has of course been down to social media and our online lives. Feminist Jessica Valentini said in 2009 that one of the major ideas, as she sees it, of fourth-wave feminism is the online activism it has inspired, suggesting that whether campaigning for women’s rights takes place online or in marches, it is within the online sphere that the ideas are conceived and propagated.

Much of this new phase appears to be about women’s bodies and freedoms.

“SlutWalks” in the US in 2011 involved marching against the victim blaming of women’s clothing in sexual assaults, and in 2021, the UK saw the gathering of hundreds of women after the kidnap and murder of a young woman, Sarah Everard, by a police officer. This was closely followed by the murders of two more women; Sabina Nessa and Ashling Murphy, leading to a suggestion by police that women not go out alone at night, followed by a controversial suggestion by Baroness Jones of the Green Party that perhaps men should have a curfew of 6pm in order to better protect women’s safety.

This new wave of feminism is going on to hold powerful men accountable for their behaviour.

Fourth-wave feminism is an inclusive feminism: many of the Gen-Z fourth-wave feminists demand equality for all sexual identities, are sex-positive, trans-inclusive, body-positive, and driven by the digital age.

There have been suggestions of something of a war between second- and third/fourth-wave feminists, and issues have arisen in recent marches with a backlash coming from some of the women involved in the second-wave feminist movement.

High-profile second-wave feminist Germaine Greer was quoted as suggesting that some women coming forward in the Harvey Weinstein case, for example, have to be held accountable for their own actions, as well as appearing to suggest that she doesn’t believe that trans women are real women, echoing the emergence of the term ‘TERF’ (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist), first recorded in 2008.

As with any political or social movement, the history of feminism will never be without its doubters and divisive topics. Racism, LGBTQ+ issues, anti-trans views, and class divides have always been an issue.

What is important is that these debates continue to be discussed within our increasingly fraught society. Embracing the work that the original feminists did - whilst acknowledging those they left out - should enhance our understanding of what it means to be a feminist, and assist us in moving into a new era of equality for all.

If you value the work that goes into writing this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber today. Your support makes this work possible.

*I also want to acknowledge that this series will not be an exhaustive coverage of the issues facing women in many countries and groups around the world, where it is still dangerous to subvert the accepted cultural identity of identifying as female. As this piece from Amnesty International shows, the fight for gender rights is still far from over.

Thanks Kate for setting out the history of western feminism so clearly and helpfully. So much work done behind the scenes to make it a fairer society.

This is a fantastic look at the different waves of feminism since it first started. It’s fascinating to see the similarities and differences between them, with each wave having its focus - and its issues. It’s great to see people still fighting for women’s rights in modern society x