"I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia"

On the love letters of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West

Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews of great books and recommended reading, please consider a free or paid subscription.

As it was Valentines Day on Friday, I thought it was an opportune time to take a closer look at one of literature’s most fascinating love affairs.

In a letter the poet, writer and esteemed gardener Vita Sackville-West wrote to her friend, the novelist Virginia Woolf in 1926, she stated: “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia…It is incredible how essential to me you have become.”1

This letter, sent during the height of their most intense love affair, went against convention; both women were already married to men, yet they continued to write love letters such as these throughout the 1920s.

In fact, Virginia’s affection for Vita would go on to inspire one of her most famous novels, Orlando, published in 1928, the story of a member of the British aristocracy who begins the novel as a young man, and ends up as a young woman, sweeping through centuries of history as it goes. Vita’s son Nigel Nicholson famously referenced the book as "the longest and most charming love letter in literature".2 It is considered one of the earliest novels with a gender fluid protagonist.

“[Orlando is] the loveliest, wisest, richest book that I have ever read…Also, you have invented a new form of Narcissism, – I confess, – I am in love with Orlando – this is a complication I had not foreseen.”

Vita to Virginia

Virginia married Leonard Woolf in 1912 after meeting him on a visit to her brother Thoby at Trinity College, Cambridge. The couple later set up a printing press together, Hogarth Press, which they utilised to publish both Virginia’s works and other writers within their milieu. Part of the infamous ‘Bloomsbury Group’, Virginia and her sister, the artist Vanessa Bell, and writers and artists such as EM Forster, Lytton Strachey and Roger Fry, were influential in developing the modernist movement in art and literature. A turning away from the large realist tomes of the earlier century, their works developed new forms and structures, written with an eye to aestheticism rather than realism.

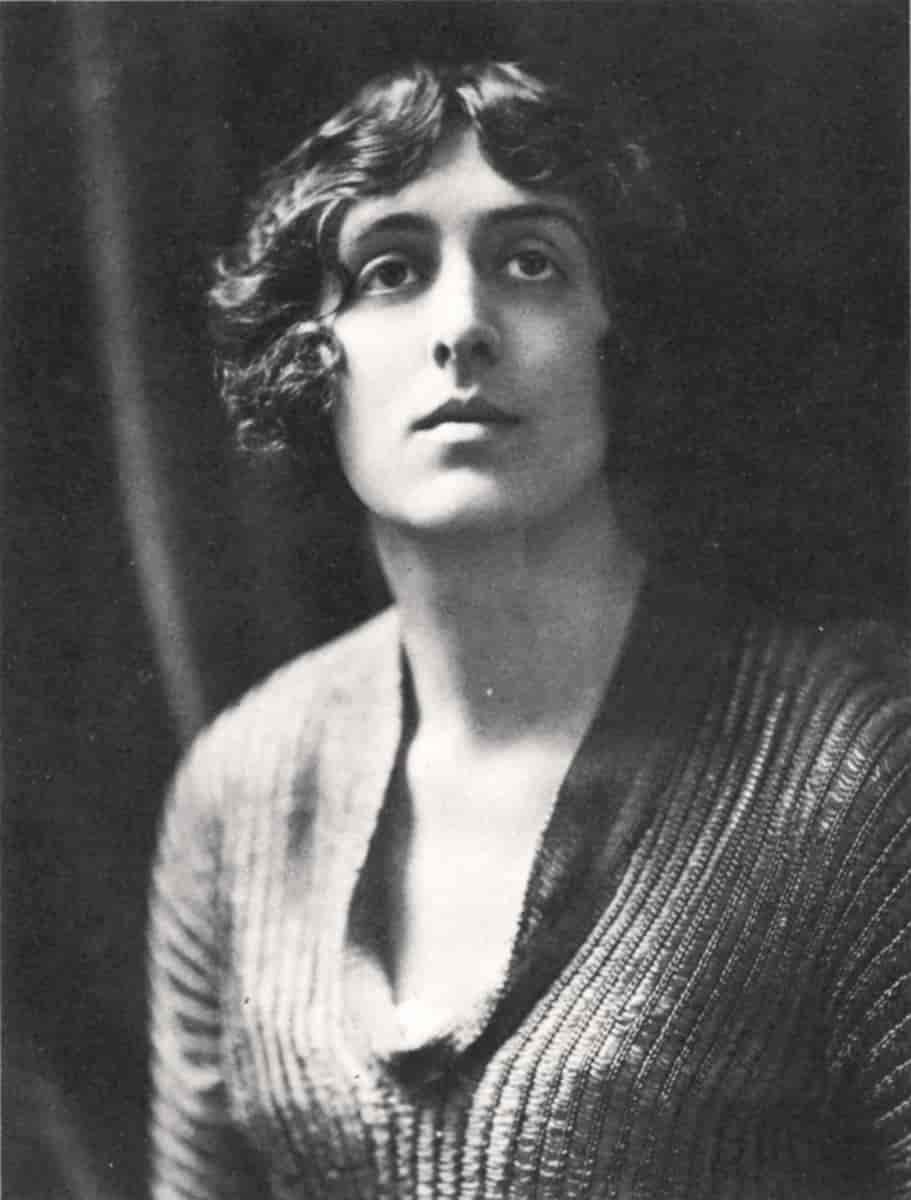

Vita, meanwhile, was also a writer, particularly of the short story genre, and was ten years Virginia’s junior. Hailing from an aristocratic family, she had grown up in the large stately home of Knole, a large estate in Sevenoaks, Kent. Vita was sadly unable to inherit the home due to the laws of primogeniture, something Virginia quite likely had in mind when she wrote Orlando, as we see the title character’s change in circumstances along with his gender throughout the book.

“You made me cry with your passages about Knole, you wretch.”

Vita to Virginia

It also influenced Virginia’s lecture given to Girton College, Cambridge, later published as A Room of One’s Own, whereby she rallied women to become financially independent in order to have the time and ‘room’ in which to write.

Vita was also married, to a diplomat named Harold Nicholson in 1913, himself also enjoying same-sex affairs during their marriage.

Vita’s son Nigel wrote a book about his parents’ open relationship in 1973, Portrait of a Marriage, where he relates their many affairs, but also their devotion to one another and to their family. He includes his mother’s own story of her obsessive love affair with Violet Trefusis, with whom she eloped to Europe in 1920, and where she strolled around the streets of Paris with her love, dressed with a bandage around her head to pass as a man.

Eventually, Harold and Violet’s husband joined forces to pursue the two women and return them to England, whereupon Vita and Harold continued their family life. However, Nigel states that when Vita met Virginia, it was the older woman that his father appeared to wish to protect, warning Vita to be wary of Virginia’s fragility.

Following their meeting at a dinner party, Vita wrote a letter to her husband Harold, mentioning her meeting with Virginia: “I simply adore Virginia Woolf, and so would you. You would fall quite flat before her charm and personality.”

Love Letters: Vita and Virginia, published in 2021, contains both letters and diary entries exchanged between the two women, showing the depth of feeling and passion they shared over almost two decades, as they tried to work out what they meant to one another.

“Mrs Woolf is so simple: she does give the impression of something big. She is utterly unaffected: there is no outward adornment – she dresses quite atrociously. At first you think she is plain; then a sort of spiritual beauty imposes itself on you, and you find a fascination in watching her… Darling, I have quite lost my heart.”

Vita sent missives to Virginia from her travels, and in her turn, Virginia would plead “Honey dearest, don’t go to Egypt please. Stay in England. Love Virginia. Take her in your arms.”

“This letter gets interrupted all the time, but I love you, Virginia – so there – and your letters make it worse – Are you pleased? I want to get home to you. Please, when you are in the south, think of me, and of the fun we should have, shall have, if you stick to your plan of going abroad with me in October.”

Vita to Virginia

But Virginia was not Vita’s only love interest: she later began an affair with another woman, Mary Campbell, leaving Virginia crushed.

“But how right I was, all the same; and to force myself on you at Richmond, and so lay the train for the explosion which happened on the sofa in my room here when you behaved so disgracefully and acquired me for ever.” Vita to Virginia

Much has been debated around Virginia and Leonard’s relationship being one of mutual love and devotion without consummation, and it would appear that Vita was Virginia’s first affair. Vita however had had several affairs with both men and women, including before, during, and after Virginia. She confessed to husband Harold that whilst she did love Virginia, she was not in love with her.

"Darling, there is no muddle anywhere! I have gone to bed with her (twice), but that’s all."

Vita to Harold

For both women, however, their relationship was a formative experience. Their letters show a flirtatious, joyous, passionate love between them, however, it also appears true that both women were happily married to their husbands.

Virginia and Vita described their relationship as "Sapphist" within their letters, taken from Sappho, the ancient poet of sensual verse about women who resided on the Greek island of Lesbos, which inspired the word ‘lesbian’.

“[Vita is] a pronounced Sapphist, and may […] have an eye on me, old though I am."

Virginia’s diary entry

Virginia appears to have been trying to make sense of her feelings towards Vita later, writing: "These Sapphists love women; friendship is never untinged with amorosity […] What is the effect of all this on me? Very mixed."

She may have been a little reticent in her diary entries, but the letters exchanged between the two women are certainly more open in discussing the more physical side of their relationship.

"Dear Mrs Woolf, (That appears to be the suitable formula.) I regret that you have been in bed, though not with me – (a less suitable formula.)"

Vita to Virginia

They also had playful codes and jokes the two of them shared, such as Virginia expressing her jealousy towards Vita’s flirtations with other women, referring to her as a "dolphin" eating "a whole bedfull of oysters.”

Both women wrote in various formats; sometimes traditionally handwritten letters, at others, a typewritten note was sent, as well as different coloured inks (Virginia favoured purple) and on different kinds of paper. They also became quite competitive in writing in the most poetic, flirtatious language possible.

"Your letters are always a shock to me, for you typewrite the envelope, and they look like a bill, and then I see your writing. A system I rather like, for the various stabs it affords me."

Vita to Virginia

When Virginia and Leonard’s joint venture, Hogarth Press, published Vita, it caused her to issue multiple letters within one parcel: one to her editor, one to her lover.

At one point, Virginia sent a portrait of herself to Vita, which remained on Vita’s writing desk; when she died, her home remained as she had left it, with two photographs: one of her husband and the one of Virginia.

They also shared their work with one another, helping to critique the writing that would later go on to be published. Though Virginia appeared the more fragile, devoted of the pair, their passion eventually subsided somewhat to a more enduring friendship.

Their last recorded meeting was on February 17th, 1941, and their last letters are dated March of that same year. It was on 28th March that Virginia left her home at Monks House for the last time. Filling her pockets with stones, she threw herself into the River Ouse. The all-consuming depression that had struck her in her youth had returned, and she could not envisage a continuation of her life with it.

Vita, writing to her husband Harold confessed: “I think I might have saved her if only I had been there.”

At the end, however, it was husband Leonard to whom Virginia wrote the last letter, a suicide note she left at their country home in Richmond.

“You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that - everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness.”

Although the story of Vita and Virginia’s passionate affair is often celebrated for its intensity and for the ways in which the two women defied the conventions of their time, I do think it’s also worth admiring the relationship Virginia and Leonard shared together, which appears to have been a genuinely loving and generous affection for one another.

If you’re new around here, I usually write about all things women literature related. My paid subscribers also receive a monthly review of great books and recommended reading. Please consider a free or paid subscription - your support helps keep this newsletter afloat!

Not into commitment? Why not contribute to my book fund instead?

Love Letters: Vita and Virginia (Penguin Random House, 2021).

Nigel Nicholson, Portrait of a Marriage, (W&N, 2024 [1973]).

This was just the kind of literary relationship gossip that I just DIE to read!!! Thank you so much for this piece, Kate! Also - I don't know where to file the reference to Virginia's preference for purple ink but I feel like I need to make sure more people know about it!

Thanks for this fine essay Kate! 👏 I love the way you embrace the breadth and depth of these people with such respect for all their complexity.