Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

The Beat Generation was a literary subculture begun by a group of authors who wrote works exploring and influencing American culture and politics, post WWII.

Some of the key names in the original Beats circle were male writers such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S Burroughs, and Neal Cassady.

Their work was seen as a rebellious rejection of the accepted societal norms, something embraced by the post-war Silent Generation known as ‘Beatniks’. Their work was regarded as bohemian, hedonistic, and a celebration of non-conformity.

But what of the Beats women?

Little interest appears to have been placed on the women of the Beat Generation at the time, with the women often fulfilling the role in the public’s consciousness as either the muse or girlfriend of the male Beats’ writers’ themselves. However, later scholars have examined some of their work further, pointing out that far from being simply the ‘hangers-on’, their presence contributed to this literary movement in a more significant way.

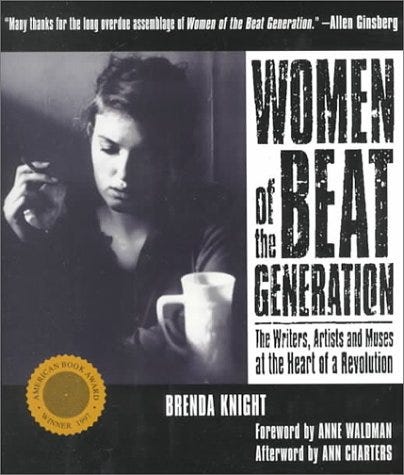

Still acknowledged as one of the foremost texts exploring the lives of the Beat Women is Brenda Knight’s Women of the Beat Generation, in which she groups together the women in named chapters such as ‘The Precursors’, ‘The Muses’, ‘The Writers’, and ‘The Artists’.1 However, this can cause confusion: many of these women would land in more than one category, often both influential on their male friends’, lovers’, or husbands’ writing, but also pursuing their own literary ambitions.

Sometimes referred to as muses for the male Beat writers, this nevertheless limits their own output and literary ambitions. In fact, many of these women were rebels themselves, fleeing their confining 1950’s homes to join the rebellious men who were forging a new genre of writing.

Women such as Joan Vollmer, who would later become the wife of William S Burroughs, and who left her comfortable home in the suburbs to attend Barnard College, and Edie Parker, leaving behind her home in Michigan to attend Columbia University and later becoming the first wife of Jack Kerouac. These two women formed a kind of literary salon within their New York apartment, where other influential members of the Beats would hang out and talk.

Joyce Johnson, meanwhile, also decided to drop out of Barnard, seeing this as living her mother’s dreams rather than her own. She made friends with Elise Cowen and Hettie Jones, both writers, and they formed a bond of female friendship and freedom away from their families. In Johnson’s own memoir Minor Characters, she describes this bold move as these women’s rejection of the status quo.

“Naturally, we fell in love with men who were rebels. We fell very quickly, believing they would take us along on their journeys and adventures. We did not expect to be rebels all by ourselves; we did not count on loneliness. Once we had found our male counterparts, we had too much blind faith to challenge the old male/female rules. We were very young and we were in over our heads. But we knew we had done something brave, practically historic. We were the first ones who had dared to leave home.” Joyce Johnson

Some of the male Beat writers claimed that they had been inspired by their women because of heartbreak or death. William S. Burroughs, for example, claimed that it was the death of Joan Vollmer which motivated much of his later writing. Allen Ginsberg also laid claim to the affecting influence of Vollmer on his writing, stating that he wrote his most famous work Howl following a dream of the dead Vollmer. His influential free verse, book-length poem features the madness of men and women and Bellevue, subjects on which Vollmer was well versed.

The novel for which Jack Kerouac is most famous, On the Road, meanwhile, opens with a passage detailing his break-up with Edie Parker Kerouac, the woman who wrote her own memoir in secret. Many of the Beat women made their way into the work of their male counterparts, though this was most often as sexual partners.

But many of these women were not interested in influencing these male writers or smoothing their ego: they wanted - and in some cases had - writing careers of their own, often after their relationships with these men ended.

Much of this literary work took the form of a memoir.

Carolyn Cassady, for example, wrote her memoir about her time with Neal Cassady, Kerouac, and Ginsberg called Off the Road. An intelligent young woman who had been raised in a strict family environment, she had an early interest in the arts and creativity. Beginning with theatre lessons at the age of nine, she began designing costumes, winning an award for this whilst still only twelve years of age. She sold her own paintings at the age of fourteen, and headed up a make-up department at the age of sixteen.

Moving to study at the University of Denver in 1946, she soon met Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Neal Cassady, beginning a relationship with the latter, who was already married to Luanne Henderson. Later, finding the two of them in bed with Allen Ginsberg one night, she ended their relationship and fled Denver.

Heading for Los Angeles to pursue costume design, she spent a brief period in San Francisco, where Neal Cassady reappeared, having divorced Luanne. She subsequently married him, the couple going on to have three children together, whilst Neal continued to spend money on cars he drove across America with his buddies and his ex-wife.

Carolyn began a long-standing affair with Kerouac after he came to live with them for a couple of months in 1952, the Cassady’s naming one of their children after the On the Road writer. She later re-lived these years in her memoir. She also continued throughout her life to work on her painting and her theatre work.

Edie Parker Kerouac, meanwhile, detailed her relationship with Jack Kerouac by writing her version of their marriage in You’ll Be Okay, My Life With Jack Kerouac, in which she relays the unbearable living conditions of the couple’s marriage. Hettie Jones, in contrast, went her own way, choosing to write a memoir around her own personal development called How I Became Hettie Jones.

Joyce Johnson interestingly focused her book Minor Characters, documenting her time with Kerouac, around the women of the Beats; the ‘minor characters’ of the title.

Growing up in Manhattan, with a similarly strict upbringing to Carolyn Cassady, Johnson eagerly rebelled. Attending university early, she also lived around two other members of the Beats elite: Joan Vollmer and William S Burroughs. Meeting another writer Elise Cowan at Barnard, she came to meet the Beats whilst they were in their New York phase.

Ginsberg, experimenting with heterosexuality at this time, was dating Cowan and arranged a blind date for Kerouac and Johnson, whereupon the pair began dating.

“The whole Beat scene had very little to do with the participation of women as artists themselves. The real communication was going on between the men, and the women were there as onlookers…You kept your mouth shut, and if you were intelligent and interested in things you might pick up what you could. It was a very masculine aesthetic.” Joyce Johnson

Although they continued dating for a couple of years, during which time On the Road was published, Kerouac fell into depression, being on the receiving end of much unwanted attention. Johnson meanwhile published her memoir, for which she won a National Book Award. The book is often seen as one of the most important works of exploration into the women’s lives of the Beat Generation. She further published a collection of letters in Door Wide Open.

But her writing achievements, unlike Carolyn Cassady and others, was not limited to memoir. Johnson also went on to write several novels as well as articles for magazines such as The New Yorker and Harper’s. Her novel Come and Join the Dance portrays a young woman named ‘Susan’, who stands as a cipher for Joyce herself and her experience amongst the Beats. Susan is a young woman who comes to discover herself as she struggles to fit into the lifestyle of a group of misfits.

Interestingly, but perhaps unsurprisingly, given the melting pot in which they were moving, there were several poets amongst the Beat women: Elise Cowen, Joyce Johnson, Hettie Jones, Joanne Kyger, Denise Levertov, Joanna McClure, Diane Di Prima, and others created their own voices through their poetry.

Diane Di Prima wrote from an early age, encouraged by such writers as Ezra Pound. Born in Brooklyn, she spent much of the 1950s and 60s living in Greenwich Village, where she became involved in the Beat movement. Later moving to San Francisco, she took a keen interest in Buddhist and Eastern philosophy.

“Where there was a strong writer who could hold her own, like Diane Di Prima, we would certainly work with her and recognize her. She was a genius.” Allen Ginsberg

On release, Di Prima’s book Memoirs of a Beatnik was criticised for being ‘pornographic’ but has since been celebrated as breaking taboos through its portrayal of a female protagonist.

But Di Prima was essentially a poet at heart, publishing first This Kind of Bird Flies Backwards in 1958, and going on to publish over forty books.

In an era which celebrated the male rebel, a rebellious female could be dealt with harshly by their families - in some cases institutionalised for their ‘wayward’ behaviour.

As precursors to the 1960s and 70s oncoming Women’s Movement of second wave feminism, many of the women who became involved with the men of the Beat Generation did so as a rebellion against their expected female societal roles of the 1950s. Following the Beat writers was surely a more enticing prospect than accepting their own mother’s lives as inevitably their own.

But as Alix Kates Shulman found when conducting research for her 1978 novel Burning Questions, a book about the rise of the Women’s Liberation Movement:

“It’s true that the Beat movement was libratory—but not really for women. As one of the many young women who had fled to Greenwich Village in 1953 at the age of twenty seeking adventure, significance, and escape from a set of materialistic, conformist values, I knew first-hand that the popular view was mistaken. In fact, however stimulating and exciting it was to be in the midst of the new jazz, art, and poetry, it was every bit as oppressive to women and as dominated by the feminine mystique and outright misogyny as square culture—and in some ways worse, since you weren’t allowed to complain.”2

Such women often left the security of their parents’ suburban homes thinking they could become the rebels themselves, but as some critics have pointed out, in the 1950s, rebelliousness was very much a male prerogative.

Even within the Beat community, they often became wives and mothers, but in a more chaotically driven situation than the reliable suburban comforts their mothers enjoyed. As with artists throughout time, the ‘great writers’ needed somebody to look after the children and keep home; that somebody, inevitably, ended up being the wives and girlfriends. Even as rebels in the eyes of their families and society, the 1950’s values were difficult to override, and the legacy of a woman’s place in the home prevailed, even in the most rebellious of frameworks.

The women of the Beat movement often conformed to the wants and needs of their male partners, assuming the accepted role of the fifties woman.

As Shulman goes on to assert, the ‘Housewife’ was often demonised by the Beats as typically ‘a devouring subverter of the freedom of men and the life-force of artists.’

Although the bourgeois idea of family was seen as something of a prison against which the bohemian artist must rebel, as Shulman points out, the Beats saw the women as the guards of such prisons, often viewing them as the embodiments of the family values, thus wishing to entrap them into the very domesticity they were attempting to evade.

Sadly, many of these women were still shackled to the misogynistic culture of their time, destined to be recognised - if they were remembered at all - as simply muses for the creation of work by their male friends and lovers. Even when they did create their own art, this was often dismissed and seen as worthless.

I embarked on this research in order to discover who the Beat women were, what they wrote, and why more isn’t written about their contributions to literature. What I found was a much larger undertaking! There were far more women Beats than I had imagined; many of whom were married or girlfriends of the same members of the bohemian group of writers, and many of which had also written books themselves.

This is such a large and rich vein of literary enquiry, and there are many more books by and about women of the Beat Generation that I haven’t covered in this essay, as well as the personal stories of the many individual women themselves. For this reason, this is a topic I may return to in future newsletters in order to examine their lives and works in more detail.

Free subscribers receive my weekly researched essays every Sunday, as well as access to community threads.

Paid subscribers also receive access to my monthly reviews and full archives. A paid subscription works out at less than £2 per month for the yearly fee, helping me to research and celebrate the important words of women.

Thank you for your support 🙂

Brenda Knight, Women of the Beat Generation: The Writers, Artists and Muses at the Heart of a Revolution (Berkeley, CA: Conari Press, 1996).

Alix Kates Shulman, ‘Women Writers in the Beat Generation, in Liber.

One of my undergraduate seminars was basically about US culture in the 20th century and we had a very large unit dedicated to the Beat generation. Needless to say, we didn't read any women--nor did we even read *about* them. I remember having a love/hate relationship with On the Road, which I read several times over that semester to write my final paper on Kerouac and the novel...but I remember very little about the book, except for its final paragraph!

I'm now going to look for Johnson's memoir, which I feel I have come across at some point before but let go for some reason...

There are SO MANY cool women in this circle and the more I learn about them, the more I get pissed that those interesting, intelligenet, sensitive men simply allowed for the women to be left out of the stories of the movement. Someone else I recently learned about was Anne Waldman - I watched the history of feminism documentary on Netflix after you mentioned it and loved getting to learn about her and her role in basically running the Jack Kerouac School.