Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

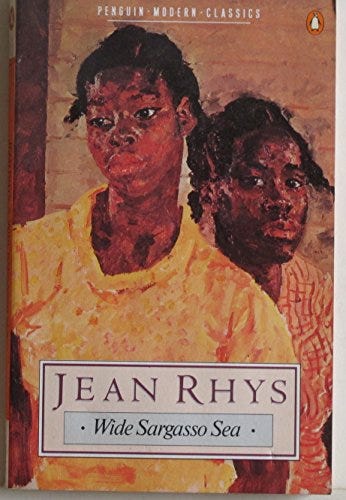

I have recently been conducting a re-reading of Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea. It has been years since I read it the first time, following a study of Jane Eyre as an undergrad in fact. To read it now as a standalone makes me want to go back to Charlotte Brontë’s classic and rediscover the attitudes to the ‘Madwoman in the Attic’, known in Brontë’s novel simply as ‘Bertha’.

Warning: Contains spoilers to both books; if you haven’t yet read either of these titles and wish to, perhaps come back to this essay later!

Brontë’s Bertha

Jane Eyre is Charlotte Brontë’s much loved classic tale of a young, impoverished, friendless girl who goes to work as a governess for the English gentleman, Mr Rochester, as a governess for his ward, a French orphan. She subsequently falls in love with Rochester, but due to her strict moral and religious beliefs, refuses to anything less than marriage.

Jane Eyre has been referred to under many guises, including social commentary, realism, Gothic, feminist and governess story. References to slavery also proliferate the text. Although references to colonial slavery are introduced, it should be noted that feminist writers in the 19th Century did consider oppressed women ‘slaves’ to marriage, something which Jane claims when refusing a proposal from another suitor later in the novel, claiming that to accompany him as a missionary to India as his assistant only would allow her to keep ‘her natural and unslaved feelings’.1

Much was also written about the situation of governesses within the 19th Century, another theme in the novel, as they were often in a delicate situation as middle-class women who had fallen on bad times and therefore had to earn a living. They were neither servants nor respected ladies, an idea alluded to in a scene of the text where Jane is discussing marriage and mistresses with Rochester. He has claimed his wish to lift Jane out of ‘governessing slavery’ and she goes on to declare ‘hiring a mistress is the next worse thing to buying a slave’. This conjures up the vision of colonial slaves for which Brontë has referenced earlier in the novel.

It wasn’t unknown for British colonialists to force Black slave women to become their concubines and Brontë’s referencing of this is perhaps deliberately pointing towards the mystery at the heart of her semi-Gothic tale: Rochester’s procuring of a wife from the colonies as well as his previous involvement with mistresses.

The scene in which Jane is finally introduced to the full horrors of the third storey of Thornfield draws the most persuasive parallels between Jane and colonial slavery in the form of Bertha Mason. This scene comes just after Jane and Rochester’s marriage ceremony is aborted due to the revelation of his existing wife, and it is no coincidence that just as Jane is about to ‘yoke’ herself to Rochester in marriage, we discover the wretched woman who has already done so. When Bertha‘s existence is first confirmed by him in the church, he reports that gossip suggests she may be ‘my cast-off mistress’. In the next chapter, Rochester will go on to suggest that Jane run away with him and take on this role, something she has already declared she despises.

Despite their apparent differences, within the attic scene we can draw many parallels between Jane and Bertha. Whilst Jane is metaphorically ‘locked in’ to her situation as a woman of no independent means, Bertha is physically locked away, held prisoner in the attic. Both women are equally powerless to change their situations. Bertha can also be seen to embody the passionate and reckless nature of Jane, something she has struggled to contain, and Brontë perhaps uses Bertha here to act as a warning.

Critics have often referred to the sense of ‘otherness’ within Jane Eyre. Bertha is continually referenced as some sort of animalistic creature, indicating an almost inhuman figure, and is ominously described as having a Creole mother, though this term in 19th Century culture was rather ambiguous and effectively referred to both white and Black people from the West Indies.

Critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak criticises Jane Eyre as not merely a feminist novel as many critics and readers have claimed, but one that recognises only the interests of ‘a minority of women at the cost of the oppression of others’.2

She goes on to make reference to Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea as a ‘partial critique of Jane Eyre’s unquestioning enmeshment in imperialist power’, claiming that Bertha becomes the ‘fictive other’ who subsequently gets destroyed ‘so that Jane Eyre can become the feminist individualist heroine of British fiction’, ultimately seeing the novel’s heroine as only reaching her full potential ‘at the cost of dehumanising her non-European counterpart, so formulating her as irredeemably ‘other’’.

Wide Sargasso Sea

Jean Rhys was born under the name Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams in Dominica, the daughter of Minna Williams (nee Lockhart), a third generation Dominican Creole, and William Rees Williams, a Welsh doctor. Though she was sent to England at the age of sixteen, she lived an often transient existence and often longed to return to her homeland.

However life had not been particularly easy for Rhys in Dominica either; the daughter of a somewhat ambivalent mother, she often felt isolated due to her whiteness amongst a predominantly Black community. She even went so far as to claim her wish that she could be Black, so as to feel more acceptable.

In her novel Wide Sargasso Sea, Rhys draws on memories of her distant childhood to return to the character of Bertha Mason, exploring her origin as a white Creole like her own mother, and creating a prehistory for Brontë’s character. In her book, she names Bertha ‘Antoinette’, a white Creole straddling the European world of her ancestors and the Caribbean culture into which she is born. Like Rhys, Antoinette is often left to her own devices, and feels closest to her old Black servant, Christophine.

At the opening of the novel, Antoinette’s mother, Annette, is widowed and has sunk into debt. She is preoccupied with Antoinette’s baby brother, who is mentally disabled. She eventually remarries a rich man named Mr Mason, hoping that he is the saviour her family need in the wake of Emancipation.

In Wide Sargasso Sea, it is Jamaica, a once lush, tropical paradise, which has become diseased and marred by death. The formerly rich Coulibri Estate on which Antoinette’s parents lived appears run-down and isolated, and the violent anger with which the Black residents of the village attack the estate reflects the immense suffering that has occurred in the region prior to Emancipation. Mr Mason constantly laughs at Annette’s repeated warnings to avoid showing his wealth, begging him to leave the Estate and move the family away.

“All Coulibri Estate had gone wild like the garden, gone to bush. No more slavery - why should anybody work? This never saddened me. I did not remember the place when it was prosperous.”3

Following the attack on her home and family which results in the death of Antoinette’s brother, Annette goes mad from grief at the death of her young son, whereupon Antoinette is sent to a school run by nuns, in which she finds refuge and safety.

Antoinette is later removed from the convent by Mr Mason, who has arranged a marriage for her to an unnamed man, but who is clearly Mr Rochester, an English gentleman. The marriage is a clear mismatch of cultures, and neither Antoinette or Rochester relate to one another.

In Part 2 of the book, Rhys cleverly writes from Rochester’s point of view, showing that he, too, has been forced into this marriage and does not understand the woman he is marrying anymore than she can relate to him.

Antoinette is now more isolated than ever: seen as white to her servants, strange in the eyes of her new husband, Rhys invites the reader to sympathise with Antoinette through her terror and anguish at her situation.

Rochester goes on to receive a letter from Antoinette’s stepbrother warning of his new wife’s depravity, stating that she comes from a family of derelicts and has madness in her blood. He begins to believe he sees such signs in her behaviour.

Then believing Antoinette has poisoned him after she actually slips him an ill-advised love potion supplied by Christophine, he takes refuge with a servant girl in the next room. Following this, Antoinette argues with her husband, begging him to stop using the name ‘Bertha’ which he has bestowed upon her without any explanation. She appears drunk and hysterical, and bites her husband’s arm during the altercation, leading Rochester to decide to leave his wife behind and return to England.

Part three of the novel returns to the narration of Antoinette, who is now locked in the attic at Thornfield under the watchful gaze of servant Grace Poole. She has no sense of time or place and does not even realise she is in England until Grace informs her. She becomes increasingly violent and frenzied, drawing a knife on her stepbrother when he visits her, but later has no memory of the incident. She recurrently dreams of burning down the house, and decides, in her insanity, that she must act on this.

The novel ends with Antoinette walking downstairs with a lighted candle from her imprisonment in the attic, foreshadowing Bertha’s fateful ending in Brontë’s own novel.

In Wide Sargasso Sea, Rhys shows a nuanced look at the forces which may have driven a woman such as Antoinette/Bertha to a state of madness. She recalls the harmful impacts of colonialism and patriarchal values, showing Antoinette’s struggle to maintain agency in a world which refuses to allow her any. She gives voice to Brontë’s madwoman, humanising her and allowing her to challenge the oppression faced by women of her race and position.

By cleverly utilising Rochester’s views in the novel, she also allows for a consideration of the discrepancies in the two world-views: he represents both the coloniser and the patriarchal forces which hold the power. Rhys shows, by interchanging their narratives, how the people in power can silence other narratives, those which may seek to question their authority.

It is a novel of oppression and oppressors, acted out through first the character of Annette, and later, Antoinette.

Neither of these women’s voices are listened to; neither of these women are free.

Although Rochester confesses that his own family have tricked him into marrying Antoinette, he is clear that he has done so for his own economic gain, caring little for his wife or who she is.

“It was all very brightly coloured, very strange, but it meant nothing to me. Nor did she, the girl I was to marry.”

In this way, Rhys aligns him with the historical repercussions of colonialism, hinting at the dominating character he will become. Like Mr Mason and Antoinette’s mother, Rochester struggles to understand the unfamiliar culture and dismisses his wife’s fears, showing his superiority and domination in the relationship.

The downward spiral into which Antoinette falls mirrors her mothers, revealing the inherent dangers in the curtailing of freedom. When Rochester receives the letter suggesting that Antoinette comes from a family of madness, it doesn’t take much to convince himself that this is his wife’s true nature. Antoinette in turn begins to act in a more erratic way.

When Antoinette realises Rochester’s infidelity with the servant girl and that he is not going to love her, she begins to spiral. When Rochester witnesses his wife’s state of mind on confronting his infidelity, he responds to her behaviour with hatred and distrust. In taking her to England and locking her away- presumably convinced that he has married a ‘madwoman’- he further adds to this perceived madness. Antoinette- or ‘Bertha’ as she has been renamed- becomes the madwoman that has been suggested is her fate all along.

In Rochester’s arrival and subsequent marriage and return to England, Rhys is clearly at pains to emphasise the dark history of colonialism in her novel, something which she has experience of. Having found England a cold and unwelcoming place, and living in various European cities including Paris, Rhys had a fondness and deep longing to return to the island of her birth. Sent out into the world at just sixteen, her sense of isolation never really went away. This is a palpable theme throughout her work.

In his novel A View of the Empire at Sunset, Caryl Phillips attempts to fictionalise Rhys’ eventual return to Dominica in 1936 with her second husband.

He opens his novel creating an image of the young Rhys as a naughty, watchful child hiding in the heavy foliage of a mango tree. Returning to the island at the end of the novel, he shows her much anticipated return as an adult. Almost as a mirroring of a true Rhys novel itself, she finds herself once again perceived as an outsider, and the trip is ultimately a heartbreaking disappointment.

In Wide Sargasso Sea, Rhys manages to flesh out the character of Antoinette throughout her development in childhood and adolescence in Jamaica, to the frighteningly desperate character of Bertha, locked in the attic and presided over by her carer, Grace Pooley, allowing for a sympathetic consideration of the mental and emotional decline of her character.

Whilst it is arguable whether Brontë was speaking out against the unfairness of imperialism and colonial slavery, particularly as Jane ultimately benefits financially from the downfall of Bertha, such intention is clear in Rhys’ narrative.

We can read Brontë’s strong sense of injustice in the lives of 19th Century women through her earlier text, but it is within Rhys’ portrayal of the impact of colonial structures, as well as the dominating factors of patriarchy, that we see the bigger picture.

Free subscribers receive my weekly researched essays every Sunday, as well as access to community threads.

Paid subscribers also receive access to my monthly reviews and full archives. A paid subscription works out at less than £2 per month for the yearly fee, helping me to research and celebrate the important words of women.

Thank you for your support 🙂

You may also enjoy my other essays on Jean Rhys:

‘The Late Revival of Jean Rhys’

‘Jean Rhys and the Mother-Daughter Complex’

‘Just Good Friends: Jean Rhys and Diana Athill’

Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, [1847] 2000, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

G.C. Spivak, Jane Eyre: A Critique of Imperialism, (1985), The Nineteenth-Century Novel: A Critical Reader, Milton Keynes: Routledge.

Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, [1966] 1968), Penguin.

Loved reading this, Kate - so well-researched and thoughtful on these fascinating themes. Reminds me of reading both at uni too and getting stuck into The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. It was one of the first books of feminist literary criticism I'd ever read and shaped so much of what - and how - I've read since.

This is an example of a novel from an earlier era which is successfully critiqued by a later writer working from a slightly more informed and "enlightened" perspective. (More recently, Percival Everett's "James" has reworked Mark Twain"s "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" in a similar fashion).