Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

Claudia Jones was born Claudia Vera Cumberbatch on 21st February 1915 in Port of Spain, Trinidad. In this period, Trinidad and Tobago were part of the British West Indian colonies.

In 1924, Jones and her family moved to settle in Harlem, New York, where Jones witnessed the exploitation of Black women workers such as her own mother, who was a garment worker. Sadly, her mother Sybil died only a few years after arriving in the US, and during the Great Depression that followed, her father Charles lost his job, leaving the family destitute.

Despite falling ill with tuberculosis, meaning a year-long stay in a sanatorium, Claudia Jones graduated high school in 1935 and around the same time became involved in social activism. She organised rallies and demonstrations, including one defending nine young Black men accused of raping two white women, known as the Scottsboro Case.

In 1936, Jones joined the Community Party of the United States of America as well as the Young Community League, where she wrote articles for the Daily Worker, the league’s journal, and quickly gained leadership positions within other organisations, such as the National Peace Council and the Women’s Commission of the Communist Party USA. She married Abraham Scholnick in 1940, but divorced in 1947, choosing to adopt the new surname of ‘Jones’ in an effort to remain anonymous whilst freely expressing her political beliefs. Although she held a strong belief in communism, she also expressed criticism at the limits of the doctrine, stating that it could not be fully successful if it did not consider the working Black woman.

‘No peace can be obtained if any women, especially those who are oppressed and impoverished, are left out of the conversation’.

To support this, she published a radical article in Political Affairs, a Marxist magazine, entitled “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman” in 1949. She claimed within her piece that Black women were exploited on the grounds of racism, sexism and classicism. Her arguments suggested that the oppression of Black women limited the success of not only the wider Black community, but also all women and the working class.

Jones’ increasing activism and work with the Communist Party inevitably brought her to the attention of the US government, leading to various arrests under the ‘Red Scare’ (also known as McCarthyism). Despite the precarious position her political activism put her in, Jones never deviated from her beliefs, and this led to various stints in prison. Her poem ‘Morning Mists’ was written during one of these, which appears to reflect her response to her incarceration.

Despite Jones being quite a prolific writer throughout her lifetime, her writing is perhaps less well known than her activism. This is partly understandable: her political convictions took precedence for her. However, a reading of some of her works shows that her politics and her writings often intersected.

“While this I know, my heart rebels

At screens that shut off sunlight’s beams

My thoughts rise too like tinkling bells

To welcome shafts of light in seams.”

Claudia Jones, Morning Mists

After being diagnosed with a heart condition and spending time in prison in 1955, Jones suffered her first heart attack and, after never becoming a full US citizen, she was deported to the UK.

Once established in the UK, she continued her important work to fight racial and sexual inequality, campaigning against workplace discrimination, unsuitable housing, and racist immigration policies.

Initially joining the UK Communist Party, Jones found her views on the patriarchy and racism were unpopular within the Party, and this therefore led her to become involved in other organisations.

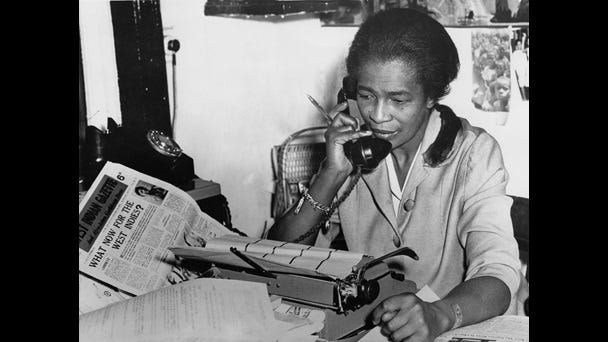

Importantly, Jones founded the first commercial Black newspaper, the West Indian Gazette, in 1958, an anti-racist newspaper designed to campaign for social equality. It featured journalism on political matters in Britain, the Caribbean, and Africa. Her aim for the newspaper was to unite West Indians and bring anti-Black violence, harassment and prejudice to the notice of the UK population. She used her journalism there to express her views on matters such as imperialism, racism, and sexism.

The same year as her radical newspaper came to print, violent riots broke out in Notting Hill, London between the white working-class inhabitants and West Indian immigrants living in both the Notting Hill and Shepherd’s Bush area of the city. The riots lasted a week and involved mostly young white individuals who violently attacked Caribbean people and their property. To try to deal with the negative feelings in the area, the following year Jones decided to set up a carnival celebrating West Indian Culture.

‘...to wash the taste of the riots from the mouths of Black people’.

The BBC network in the UK televised the first ever carnival, which featured West Indian culture and heritage, at St Pancras Town Hall. The carnival now known as the Notting Hill Carnival still continues today, grown to be the second largest street carnival in the world. It is an uproarious celebration of music and dance, with many food stalls, artists and activists celebrating West Indian culture.

Despite her exile in the UK, Jones continued to monitor the work of the American Civil Rights Movement, and in support of Martin Luther King, Jnr and the March on Washington in 1963, she organised a similar march to the US embassy in London.

Sadly, Jones died a year later at the age of just 49, having struggled with ill-health for most of her adult life. A large funeral procession was held in her honour. She left a legacy of work behind, showing her continued, life-long attempts to improve not just the lives of Black women workers, but towards a more equal society for all.

This is the free version of my newsletter for all subscribers. I have recently reduced my paid tiers to allow for all budgets who would like to support the work I do here, uncovering the narratives of women. Paid subscriptions help me to continue to write and research quality newsletters every week - and the yearly fee works out at less than £2 per month! Tap here if you’d like to consider an upgrade. Thank you for reading 😀

I've never heard of this incredible woman before, thank you for introducing her story!

Great post, thank you Kate. What an incredible woman. What else she could have achieved if her life wasn’t so tragically short.