Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

As an essayist who also works part time for the NHS, I operate on a patron model, to allow my writing and research to remain free for all. If you value my work, and are in a position to support this financially, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Thank you for your support.

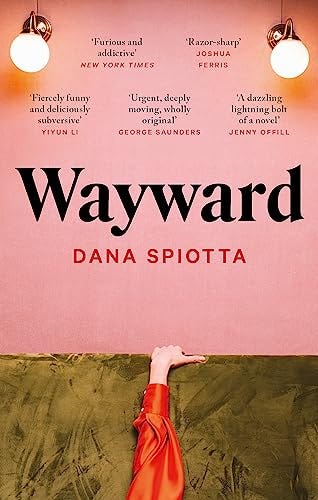

I came to Wayward after hearing the author Dana Spiotta speaking about it on the Virago podcast, OurShelves.

The book is about Sam Raymond, a fifty-two year old woman staring into what she calls ‘The Mids’: “the night-time hours of supreme wakefulness when women of a certain age contemplate their lives”.1 For Sam Raymond, this contemplation involves motherhood, mortality, and the state of the nation following Trump’s 2017 inauguration.

The book opens when an increasingly frustrated and exhausted Sam falls in love with an Arts and Crafts house on the wrong side of Syracuse and decides to buy it, subsequently fleeing her suburban life with her husband Matt and teenage daughter, Ally.

“The decision to leave her husband - the act of leaving, really - began the moment she made an offer on the house.”

Sam’s flight is interesting in that it doesn’t follow old tropes: she doesn’t fall for another man, but a house.

It’s also interesting in that she and her husband maintain some kind of convoluted relationship throughout the book; part friendship, part lovers. She doesn’t appear to have any real issues with either him or the marriage except that he cannot fathom her deep despair over the Trump administration. What appears to be happening in fact is that she is recoiling into the life she felt she had before her marriage, when she and Matt were lovers and the attraction he felt for her was, in part, her impetuous and daring nature. When he visits her in her new home, they always end up in bed together, in a re-enactment of their early relationship.

This idea, of wanting to return to an earlier version of yourself, really rang true to me, and I thought it was an interesting twist on the narrative of the ageing ‘hag’ that has featured in recent books on midlife transition. What is never really mentioned in many of these stories is that this time can bring an almost feverish anticipation of a new era in a woman’s life - one that can either be feared or embraced - and I feel that Spiotta is aiming to show this turmoil in Sam’s struggles with whom she is becoming.

This also reminded me of Love and Trouble by the brilliant essayist and social commentator Claire Dederer. In it, she refers to ‘that awful girl’ she used to be, referencing her wild and awkward youth and sexual awakening, and how, when entering the middle of her life, she begins to retreat to her garden writing shed in order to pore over old teenage diaries and see herself re-emerging into that old self. This is something she doesn’t welcome, but feels unable to control, like a second adolescence.

Various things begin to happen to Sam in Wayward when she moves into the run-down yet architecturally beautiful house.

She makes friends with two women she meets in an online forum and ends up being talked into doing stand-up comedy about her life. She muse’s over cancel culture when one of the women posts something unthinkable online. Later, she witnesses the shooting of a young Black teenager on the streets of the city during her late night wanderings.

There was a lot to unpack in this novel, and I was keen to read it for the connections I was hoping to find with Sam.

I have written before about the fate of the middle aged woman and invisibility, and it can be hard to find good representations of their stories in fiction. Often, what I have found with other books are acerbic encounters with the typified angry middle aged woman who is raging about their transition into middle-age, envying their younger daughters, and dubiously ‘humorous’ portrayals of hot flashes, moments of road rage, and women taking off into the night, leaving behind cowering partners and children in their wake.

I can see the reasons behind this. The fate of the middle aged woman, facing down countless physical ailments together with an often unsympathetic stereotype, not to mention the overwhelming anxieties of What’s next…? can leave women at this time in their lives, at the very least, frustrated.

However, I do find that these narratives are often quite limiting.

I don’t want to enrage anyone who is going through this stage of life (Hi! Right there with you!) But I do feel that, like a lot of accepted narratives at the moment, it is easy to feed into the stereotypes.

I ordered Spiotta’s book because I liked the way Sam Raymond sounded like someone who took agency for her own life, and I thought her story would resonate with me.

It’s a smart book, although I can’t help feeling it’s a bit confused as to whether it wants to be a personal journey through the pitfalls of ageing, motherhood, and the loss of a parent in a Gen-X woman - what is often known as ‘The Sandwich Generation’ (meaning both having the responsibility of children still at home whilst simultaneously caring for an ageing parent), or whether it is a political tract on the state of US politics and racism.

I think, quite possibly, this is Spiotta’s point: for women, the personal is political, as was the old feminist mantra of the 1960s and 70s.

What I found uncomfortable and difficult to align with, however, was Sam’s situation in life. She falls in love with the house at the beginning of the book, and makes an offer. She also realises the house means she will leave her husband, though it hasn’t presumably occurred to her before this point. I feel this underlines Spiotta’s character as someone many women would not be able to associate with: her financial situation and class means she can readily agree to purchase a second home.

She also tells husband Matt that she doesn’t have the bandwidth to deal with her daughter’s college applications. She is effectively wiping her hands clean of the whole ‘family-thing’ in a way that I think would feel unrealistic to most mothers.

But Spiotta also gave me such moments of recognition throughout Sam’s narrative that I found myself nodding in agreement, putting down the book to contemplate what I had just read.

For example, after Sam finds a homeless young woman sitting on her front step and gives her some soup and some money to leave, she questions herself as to why she didn’t invite her inside and help her more. She realises at this point that she just couldn’t face the responsibility of taking on anyone else’s problems:

“...that this person and her problems would become Sam’s responsibility: what had gone wrong, where she slept, what she needed. Responsibility, that’s what Sam didn’t want.”

This hit me on first reading and I had to stop and think about it for a while.

As a woman of a similar age, I have found it difficult over the past few months to describe exactly this feeling: the feeling that, as a woman and a mother, it feels like you are (metaphorically and sometimes literally) eternally mopping up around other people. I find that, in Sam’s revelation that she doesn’t want the responsibility, we see the reason for what seems like an unnecessary move across town to a random house overlooking the city, where she lies night after night on a mattress by the open fireplace, worrying about the world.

This is a clever way of Spiotta handling the feelings of a woman going through this transition: she doesn’t spell it out, leaving readers to wonder what is wrong with narrator’s perfectly comfortable home life in suburbia, instead revealing Sam’s head space through her refusal to become involved in anything other than the basics of keeping herself alive.

In Sam’s refusal to accept the political landscape of 2017, she struggles to make sense of her own inner world, and that of the other females in her life: the likely loss of her mother in the near future and the legacy passed on to her daughter, who pushes herself too hard in order to achieve. Interestingly, she chooses to insert Ally’s narrative into some sections of the book, allowing for an understanding of her head space as she wonders at the behaviour of her ‘crazed’ mother, and refuses to acknowledge her text messages.

But Ally has secrets of her own, and we see her developing an illicit relationship with an older man who is meant to be her mentor. A touching moment comes later in the book when Sam encounters them at the state fair but pretends not to see them. She realises in this moment that she must let go of the need to always control her daughter’s life, and that perhaps it is her way of smothering her child that has often led to the distance between them.

Similarly, it is Ally to whom Sam’s mother confesses her illness first, understanding that Sam cannot deal with it in her current state. In one of the most beautiful descriptions of a mother I have ever come across, Sam eventually comes to terms with the impending loss of her mother, realising that her mother, herself, and her daughter are eternally connected in a female lineage that will continue. This brings her great solace and a peace she has been unable to locate for some time.

“Sam was from her, a part of her, and Sam would feel, in a profound way, that she remained a version of her, a derivative.”

Ultimately, this was a book I took a lot from, and it stayed with me for days after reading the last page.

I think that, though Sam’s situation was undoubtedly privileged, as well as unrealistic in the way that women (especially mothers) cannot and do not often get to walk away when they feel the pressure, it also didn’t ‘idealise’ the concept of being able to walk away. When Sam finds herself alone in her house, she doesn’t suddenly experience a moment of clarity, where midlife no longer feels like a foreign land.

It reminds us that our lives as women are complex, and that we are affected by the society and landscapes around us. It reminded me that being a daughter of a daughter of a daughter…Ad infinitum is a legacy handed down through the generations, and that the ways in which we conduct and project ourselves and our needs as middle-aged women is a narrative that demands to be told.

Fascinating books, and discussion, Kate! I'm adding these to my library list. The presence of housing and real estate in our love stories is always of interest to me (hello, Pemberley 😊) ❣️

This sounds like a fascinating look at an important time in a woman’s life. I’m glad the book resonated with you, and it’s great to see a piece of fiction that doesn’t follow the typical stereotypes of this time in life. Thank you for sharing :)