The Price of Salt

Exploring Patricia Highsmith's celebrated lesbian novel

Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

This week, as we are officially in Pride month in the UK, I wanted to explore what is often credited as the first lesbian novel with a happy ending: Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (later re-published as Carol).

Patricia Highsmith was a celebrated writer who wrote some of the most iconic 20th century suspense thrillers such as Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr Ripley, which went on to be recognised as iconic films.

But perhaps her most fascinating novel for the purposes of today’s post is her 1952 lesbian romance novel The Price of Salt (later renamed Carol).

Highsmith published some 22 novels and short stories, and despite enjoying relationships with women, Salt/Carol is her only specifically lesbian fiction.

In the 2010 edition of Carol, Highsmith’s afterword is illuminating. She states that she got the inspiration for A Price of Salt in 1948 whilst working as a salesgirl in a big department store in Manhattan during the Christmas rush. She had just finished Strangers on a Train but was strapped for cash whist waiting for it to be published. The job working in the toy section (as central character Therese does in the novel) lasted a mere two and a half weeks, but it was enough time for a woman to catch her eye and inspire her imagination.

Highsmith refers to spotting a:

‘blondish woman in a fur coat’ whom caused the young Patricia to feel ‘odd and swimmy in the head, near to fainting, yet at the same time uplifted, as if I had seen a vision’.1

Highsmith wrote out the plot for A Price of Salt that evening in her apartment where she lived alone, taking less than two hours to complete the first short draft.

She never returned to the store on Monday morning, as she discovered she had caught chickenpox (possibly from one of the children who visited the toy store over the weekend), and shortly afterwards, the publisher of Strangers on a Train informed her that Alfred Hitchcock wished to make the book into a film. They encouraged her to write another novel of the same type to strengthen her reputation.

But Highsmith states that she was confused by this idea. Harper & Bros had published the novel under the title of ‘A Harper Novel of Suspense’, pushing her into the mould of suspense writer, though she did not see the book in any such category.

She wondered whether her newly forming novel A Price of Salt would therefore push her towards becoming a lesbian-book writer.

Deciding that she may never be inspired to write another book in the vein of A Price of Salt, she decided to pursue publication under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, completing this in 1951 and refusing to commit to another suspense novel during this time, stating that she could not write a different novel simply for commercial reasons whilst she worked on this.

Her publishers at Harper & Bros rejected Salt, however, forcing her to find an alternative US publisher. She was unhappy about this, but managed to secure an independent publisher, Coward McCann, which garnered a few respectable and serious reviews to the hardcover in 1952, whilst going on to sell almost a million copies of the paperback a year later.

Highsmith says she recalls receiving envelopes via her publisher with ten to fifteen letters a couple of times a week for months, many of which she answered.

As Highsmith points out, at the time, gay bars in Manhattan were often hidden behind dark doors where people got off the subway a stop before or after to avoid suspicion of being homosexual. She claims that the success and appeal of her novel was down to the fact that her two main characters have a happy ending at the end of the book. This was an unusual trait for gay or lesbian fiction, whereby homosexual characters, according to Highsmith, often had to:

‘pay for their deviation by cutting their wrists, drowning themselves in a swimming pool, or by switching to heterosexuality (so it was stated), or by collapsing – alone and miserable and shunned – into a depression equal to hell’.

On this note, Val McDermid, in her introduction to the 2010 edition, states that the novel:

‘didn’t so much fill a niche as a gaping void’.2

She points out, as did Highsmith, that the popularly presented image of lesbians in literature were as:

‘miserable inverts or scandalous denizens of titillating pulp fiction’.

Highsmith’s novel, in comparison, presented the relationship between two women with a serious, erotic, and classy prose, breaking the mould for such fiction.

Whilst the book was a departure from Highsmith’s classic suspense fiction, McDermid makes the point that it remains typically representative of the author. The novel contains a tight psychodrama within its storyline, forcing its characters into moral dilemmas and a tense, suspenseful pitch which reads like a thriller.

The plot involves the protagonist Therese Belivet, an aspiring stage designer who is engaged to be married. The ‘blondish’ woman she encounters in the toy department is Carol Aird, a woman going through a difficult divorce who visits the store to purchase a toy for her daughter.

The two women are drawn to one another but neither knows what to do with this attraction and they initially attempt to form a friendship, though their deeper attraction prevails. Missing her daughter, Carol persuades Therese to take a road trip with her, where their relationship develops. Their happiness is threatened – and the thriller-esque tension therefore heightened – when they are pursued by a private investigator hired by Carol’s husband.

The story’s pace and intensity makes for an addictive read. What is also interesting, as McDermid points out in her introduction, is the comment it makes on American middle-class society of the 1950s, particularly regarding the cynicism around middle class respectability. She also implores the reader not to class this novel as gay genre fiction, instead claiming its place within significant literature having a universal application.

Despite this, the novel remained neglected for many years (as is often the case with some of the later discovered works of women). McDermid states this was initially due to the subject matter, claiming that later lesbians were unaware of the book. As she points out, if it had originally been published in Highsmith’s name, as an author of note, it may have been more widely read. This didn’t happen in the US until 1991, however, when it was republished by Naiad Press, when it became lost in the proliferation of more edgy, emerging lesbian fiction of the 80s and 90s.

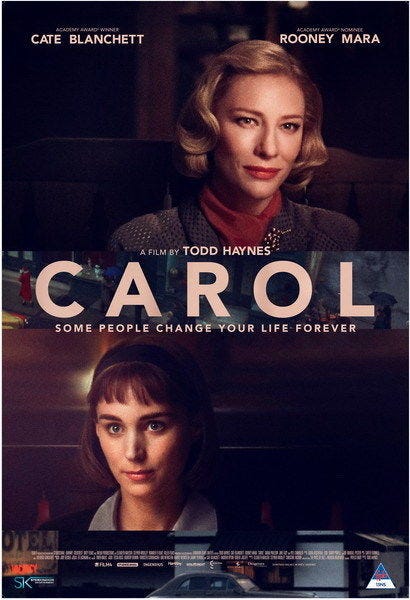

Thankfully, Carol has gone on to flourish in a newer crop of more literary lesbian fiction, fitting amongst writers such as Jeanette Winterson, Ali Smith, and Sarah Waters. The 2015 movie of the same name starring Cate Blanchet as Carol perhaps helped to secure the success of this thrilling novel.

Highsmith states that many of the letters she received had messages celebrating the fact of her happy ending in Salt, letting her know that: ‘We don’t all commit suicide and lots of us are doing fine’. Others simply stated: ‘Thank you for writing such a story. It is a little like my own story…’ As well as some heart-breaking ones informing Highsmith that, because of their location in small town America, they felt they had nobody to talk to about their own situations. Highsmith says she sometimes wrote back to those readers advising them to try moving to a larger city where they may meet more people.

McDermid calls into question the idea of a ‘happy ending’ to the novel, however, as Carol pays a high price for following her heart. The future for Carol and Therese will remain complex, though she acknowledges that the very fact of the ending not requiring either woman to be ‘saved’ by the love of a good man significant.

‘Some books change lives. This is one of them.’ Val McDermid

Despite the novel’s central female characters, Highsmith says she received as many letters from men as women. She saw this as a good omen for the book, and as of writing the afterword for this edition (1989), she claimed the letters continued to trickle in over the years, still receiving a couple every now and then.

Interestingly (and rather ironically) Highsmith ends her afterword stating that she never wrote another novel like A Price of Salt. Her next book was The Blunderer, another one of the thriller novels for which she will be most remembered. However, as she put it:

‘I like to avoid labels. It is American publishers who love them’.

Postscript: If you enjoyed this post, you might like my discussion on Rubyfruit Jungle by Rita Mae Brown. Also, sign up for a free or paid subscription to my newsletter for more recommended reading for Pride month at the end of June!

Patricia Highsmith, ‘Afterword’, Carol, [1952], (2010). *All further references to this edition.

Val McDermid, ‘Introduction’, Carol, [1952], (2010). *All further references to this edition.

Having both seen the film and read the book I found your piece an interesting read, thank you.

Thanks, Kate. I haven’t read Carol or seen the film, but definitely want to now. And I agree with the other comments about the original title. It was interesting to read about her relationship with her publishers too. Thanks for a great read!