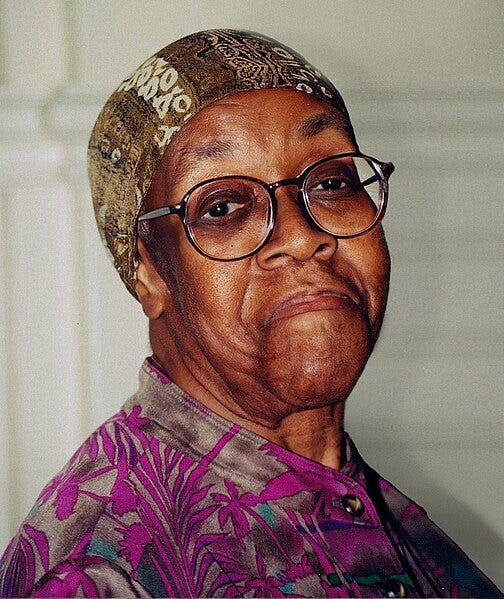

Twentieth-century poet Gwendolyn Brooks was Born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917, though grew up in Chicago. Her janitor father and school teacher mother supported her love of reading and books, and Brooks had her first poem published at the age of just 13 in American Childhood. By the age of 17, she was publishing widely, and after graduating college in 1936, worked for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), publishing her first poetry collection A Street in Bronzeville in 1945. The name of the book is taken from journalists’ slang for Chicago’s Black ghetto.

“I felt that I had to write. Even if I had never been published, I knew that I would go on writing, enjoying it and experiencing the challenge”.

More than twenty books followed, revealing her talent for representing the ordinary, urban daily lives of her neighbourhood. This led to her becoming one of the highest read poets of the twentieth century, as well as becoming the first African American poet to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1950 for her collection Annie Allen, a loosely connected series of poems relating to an African American girl growing up in Chicago. She also became the first to hold the role of Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, serving as the Illinois poet laureate for thirty-two years.

Amongst the poets from whose inspiration she drew, Brooks was said to have been influenced after meeting James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes, who encouraged her reading of modernist poetry and the need to write with disciplined regularity. As well as being a proficient poet, Brooks was committed to racial equality and identity, with many of her poems written in celebration of the Black urban poor.

“We don’t ask a flower any special reason for its existence. We just look at it and are able to accept it as being something different from ourselves.”

An influential change occurred following Brooks’ attendance in 1967 at the Fisk University Second Black Writers' Conference. There, she met new, young Black poets whose poetry and social thinking inspired her involvement in the Black Arts movement. This new adoption of ‘the black aesthetic’ led to her potential role as a Black feminist leader. Her poetry also changed to become more influenced by the improvisations of jazz and the spoken language of the Black community.

We Real Cool

The Pool Players.

Seven at the Golden Shovel.We real cool. We

Left school. WeLurk late. We

Strike straight. WeSing sin. We

Thin gin. WeJazz June. We

Die soon.

Brooks’ poetry spans the range of traditional forms including ballads and sonnets to the familiar rhythms of the blues and free verse. In this way, she remarkably utilised all the popular forms of English poetry, as well as the use of the lyric and long narrative poems.

“Poetry is life distilled”.

Brooks also wrote one novel, Maud Martha, in 1953, a novel in short vignettes whereby the title character suffers racial prejudice from both white people and lighter-skinned African Americans, something which mirrored her own experiences. Her later poetry became more politically leaning, touching on the effects of colour and justice. It was noted by critics that Brooks’ work after the age of 50 showed a new movement and energy with a leaner style of poetry, suggested to be the effect of the gathering of Black writers at Fisk University in 1967.

Brooks herself noted this change in her writing, commenting that:

“Those young black writers seemed so proud and committed to their own people. The poets among them felt that black poets should write as blacks, about blacks, and address themselves to blacks”. Poetry Foundation

She also claimed that it was this interaction with young Black writers which allowed her to know herself:

“If it hadn’t been for these young people, these young writers who influenced me, I wouldn’t know what I know about this society. By associating with them I know who I am”.

This, by her own admission, led to her thinking of herself as an African who would not compromise her identity in order to write her technically gifted poetry. In her poem ‘In the Mecca’, for example, taken from a collection of the same name, Brooks shows a mother who loses her small daughter in the middle of a ghetto tenement known as ‘the Mecca’. The poem reveals the neighbours of the tenement as the mother wanders it looking for her daughter, showing the way they are closed into their own problems. She eventually locates her child, commenting that she ‘never learned that black is not beloved’. The collection contains slices of urban life, and also has a poem written following the death of Malcolm X, showing Brooks’ commitments to her political and cultural identity.

Following the influence of the young Black writers at Fisk, Brooks left her original publishing house to join new Black publishing companies, including Broadside Press, who published several collections in the 1960s and 70s, and Third World Press. She expressed her disappointment, however, that some of these collections did not receive the same notice from critics, accusing the literary establishment of not wanting to encourage Black publishers.

Brooks wrote two volumes of autobiography, receiving a certain amount of criticism that they lacked personal insight. Brooks put this down to critics wanting ‘a list of domestic spats’. Other critics celebrated what they saw as her new orientation toward her racial heritage in combination with her role as poet.

Serving as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, Brooks saw her most important role in visiting schools, colleges, universities, prisons, hospitals, and drug rehabilitation centres, including setting up sponsorship for annual literary awards out of her own pocket. This led to several schools being named in her honour, as well as the founding of Western Illinois University’s Gwendolyn Brooks Cultural Center.

Brooks received a lifetime achievement award in 1989 from the National Endowment for the Arts, and took the position of Professor of English at Chicago State University in 1990 until her death in December 2000 at the age of 83.

This just shows how her determination has had the most amazing ripple throughout communities. Poetry is often not seen as ‘mainstream’ however the beauty of the writing is so powerful. Great piece about an incredible person. Thank you.

Kate, this is one of my favorite writers ever! Thanks for the great post. Her anthology of work - Blacks - is often off my bookshelf for research or just some fun reading. I really love the way she describes places like the hair salon as well natural images - like pigeons. She has a lot to say about the beauty of Black culture and women as well as reflections on everyday life.

I didn't know she was visiting so many places as you explain here, and it was interesting you said drug rehab centers, because there is this beautiful film from the Robert Pinsky Project with a man from Boston who talks about this kind of influence from the poem "We Real Cool" - just a few minutes, worth a watch for any of your readers. I've showed it to endless high school students. :)

GREAT CHOICE!

https://www.favoritepoem.org/poems/we-real-cool/