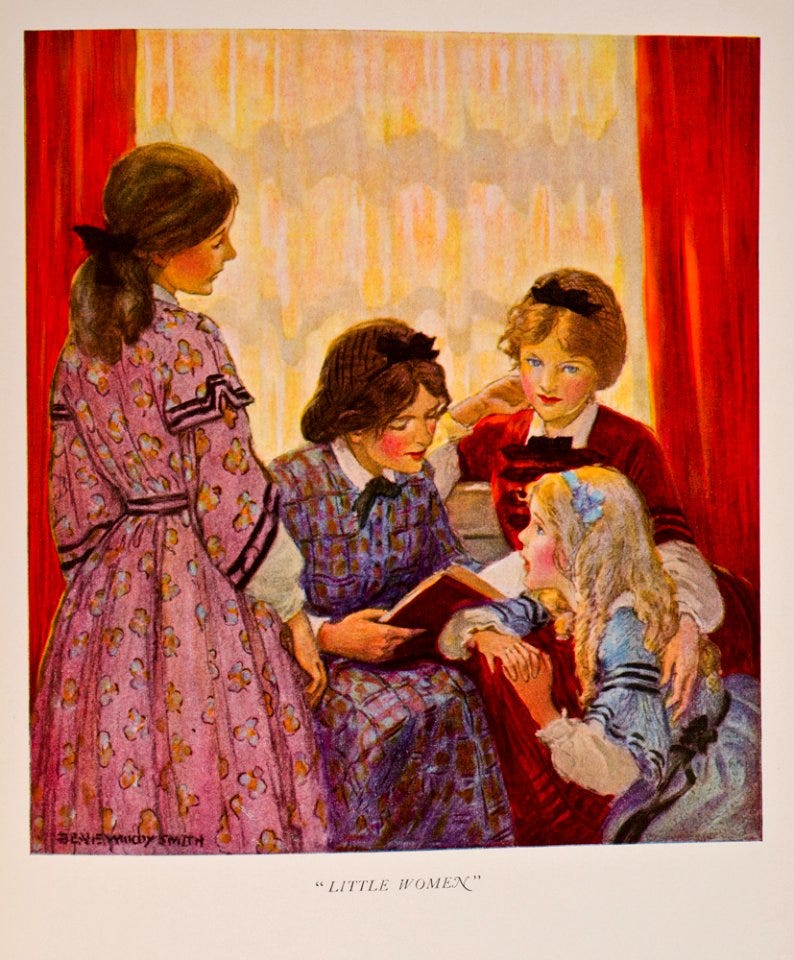

Little Women

Returning to Louisa May Alcott's Classic

Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews of great books and recommended reading, please consider a free or paid subscription.

When I was growing up, the Christmas season contained several stalwart traditions, but by far my favourite was of my mother and I watching a film version of Little Women over the festive period.

My mother’s personal favourite was the 1933 version with Katherine Hepburn as Jo March, the feisty writing sister that every young girl who wrote dreamed of becoming.

We also enjoyed the 1949 film starring June Allyson as Jo, with her winning smile, and later, the 1995 film starring Winona Ryder in the main role, which we both agreed had its merits, though Mother advised that “Ryder couldn’t quite do Jo like Hepburn did Jo…”.

I knew when not to argue.

I can’t quite recall when I first read Louisa May Alcott’s treasured classic rather than watched it - probably a children’s abridged version I owned and that my mother read to me in bed - but to be honest, the book and the films have merged somewhat in my mind over the years such that they are inseparable. All I really know is that they spell out Christmas to me.

So last year, my grown daughter and I continued the tradition and watched Greta Gerwig’s 2019 version of the book which, to be frank, left me a bit disappointed. “Saoirse Ronan couldn’t quite do Jo like Hepburn did Jo…”, I found myself saying. (Truism: we all turn into our mothers’ sooner or later…).

But what it made me realise- as I was arguing about the ways in which Gerwig played fast and loose with both the book and Alcott’s true life story in an attempt to address the inequalities for women in Alcott’s world- was that I hadn’t actually read the book in such a long time that I didn’t remember which film would be the truest representation of the novel. Furthermore, perhaps my knowledge of the real life of its author has coloured my own experience of the story.

After my daughter gifted me a beautiful copy of the book for my birthday earlier this year, I decided it was time to return to this classic; to re-read what I always profess to be one of the most important books of my life, and to see whether it held up to time and my own tastes.

I also wanted to learn more about the writer of this classic, to see if her own life affected her portrayal of the four sisters growing up during the American Civil War.

This is what I found…

Little Women was written by Louisa May Alcott in 1868 and is what is known as a Künstlerroman, meaning an ‘artist's novel’ in English. It is a narrative about an artist's growth to maturity, that artist being Jo March, the second eldest of the four March sisters, living in Concord, Massachusetts, during the American Civil War.

The book could also be classified as a subcategory of the Künstlerroman, a Bildungsroman, which signifies a coming-of-age novel, dealing with a person’s formative years or spiritual education, and Alcott’s book runs a parallel alongside John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, which each of the sister’s receive for Christmas at the start of the story and attempt to read and follow.

Joanna Biggs in her memoir A Life of One’s Own states her belief that Little Women is a Kunslterroman nestled within a Bildungsroman: “the story of all these women growing up is also the story of them learning to write, or more than that, discovering the possibilities that writing offers.”1

Although the book tells the story of all the four March sisters, it is Jo March who stands centre-stage and with whom the enduring affection of the novel belongs.

The original publication of the book was by Roberts’ Brothers in Boston, and appeared in two volumes: the first in October 1868 and the second in April 1869. Both novels were titled: Little Women, or, Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy. The second book simply bore the subtitle: “Part Second.”

However, in 1880, the two books were combined together under the simplified title of Little Women that we now recognise. The chapters were renumbered to run along into one text, and this has remained the predominant publishing feature in the United States ever since. In England, however, the second volume of the text was renamed Good Wives. Elaine Showalter, writing the introduction to my edition, points out that this was most certainly not a decision made by Alcott herself, confirming that the author would have scorned such a demoralising title. However, it is this format which has remained to the present day, and the style in which I first encountered the book.

Showalter also points out that Alcott made some alterations to the text in 1880, grammatically changing some points as well as modifying her diction in places, to suit the publisher’s version of “ladylike prose.” Showalter chose to present the edition I now have in its initial, uncorrected form and under the single title of Little Women, which she believes most closely follows the intentions of Alcott herself.

A quote appears at the front of the book taken from Simone de Beauvior’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, expressing her love for Alcott’s story and her identification with the rebellious Jo. She claimed that this inspired her to write her own stories and shun the idea of sewing and housekeeping, switching these instead for a love of books. As Showalter points out, there are many similar testimonials to Alcott and her eponymous character of Jo March from other female writers.

However, far from being considered a classic throughout its history, Showalter asserts that many male writers considered it too sentimental and full of female piety to be considered a classic work of literature, despite doubts raised over whether such writers had actually read the book. In fact, as she points out, Alcott often writes unsentimentally of death within the text, using both humour and an air of detachment. It was not considered a text worth further literary analysis by scholars, however as Showalter determines:

“There can be few other books in American literary history which have had so enormous an impact on the imagination of half the reading population, and have been so neglected by the other half.”2

Happily, the tide has turned in the past few decades meaning that Alcott’s book, along with other female writers of the era, have been studied by leading feminist critics, such as Nina Auerbach, who interprets Alcott’s story as a novel about self-sustaining communities of women, whilst Judith Fetterley considers it as Alcott’s own personal “Civil War” between conflicting impulses of femininity and creativity. Still others have discussed it as an important feminist critique on the Transcendentalist movement.

Famously, Alcott was coerced by her publishers to end the story of the March sisters with a marriage proposal for Jo, an independent young woman who harbours ambitions to become a paid writer. Gerwig, directing her version of the novel, chooses to represent this episode of Alcott’s real-life experience by showing the character of Jo arguing with her publisher towards the end of the film, when he confirms that readers will want Jo married to a suitable man at the end of the book.

Alcott herself never married nor had any children of her own. She did however take in her niece, Louisa May Nieriker, known as Lulu, following the death of her younger sister May.

“I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe.” Louisa May Alcott

Alcott was also a fervent abolitionist, active in reform movements such as temperance and women’s suffrage. She likely inherited this socially progressive nature from her mother Abigail Alcott, who was also an activist and one of the first paid City Missionaries, or Social Workers, in the state of Massachusetts.

Disappointingly to many readers, Jo does not end up marrying long-time friend of the family Laurie (Theodore Laurence), the rich neighbour who despite being from a wealthy family, has no siblings of his own and longs to be part of the March family. Jo brings him out of his shell and he falls in love with the whole family, eventually proposing to Jo, who turns him down, preferring to love him as a brother.

“I can’t say ‘Yes’ truly, so I won’t say it at all…you’ll get over this after a while, and find some lovely, accomplished girl, who will adore you, and make a fine mistress for your fine house. I shouldn’t. I’m homely, and awkward, and odd, and old, and you’d be ashamed of me…”.3

Like the sisters of the novel, Louisa May Alcott considered herself a dutiful daughter, stating that her greatest ambition in life was to be “a good daughter” to both her parents, rather than “a great writer.” Alcott’s father was a moralising influence on her, and feminist critics have pointed out that her true creative potential could never be fully realised as long as she attempted to contend with his moralistic viewpoints, the commercialisation her publishers insisted on putting onto her writing, and the puritanism of the Concord of her home. Alcott’s father, Amos Bronson Alcott (known as Bronson), was an eccentric seer of American Transcendentalism, who, amongst other things, was a social reformer known to such contemporary luminaries as Emerson and Hawthorne. His antimaterialist beliefs meant that he was practically incapable of earning money, leading his daughter Louisa to feel obligated to help with the family’s finances.

Alcott’s mother Abigail (Abba) May Alcott, meanwhile, was an imaginative and quick-tempered woman whom the family agreed Louisa took after the most. As I re-read the book, it became evident that “Marmee” represents the real-life beloved mother Abba, and that Mrs March’s advice to Jo’s often hot-headedness, claiming a kinship with her creative daughter, is a direct translation of this.

“The mother and daughter are a part of one another and cannot be separated long at a time.” Amos Bronson Alcott

Louisa dedicated much of her work to her mother and nursed her right through her last illness, claiming that her finest deed of her life had been to make her mother’s final ones happy. Showalter claims they had a lifelong attachment and interdependence, making their mother-daughter bond unbreakable. What also appears crucially clear however is that such a bond in-arguably bound Louisa to both her mother and her family, making the puritanical ethic of self-sacrifice a difficult bond to break. As Showalter points out: “she was never able to break away from her mother to forge an independent life.”

If Abba encouraged her daughter’s creative ambitions, her father Bronson cast her as ‘difficult,’ attempting to tame her natural personality and teach her feminine decorum and self-control. This part of Alcott’s upbringing marries well with her novel; the girls are often encouraged to self-sacrifice by their mother acting as proxy on behalf of their absent father, who is away fighting in the American Civil War. Though the words are often spoken by Marmee, they are delivered on behalf of their ‘Papa’, who wishes them to remain his good and brave ‘little women’ whilst he is gone. Jo is perpetually taught to hold her tongue and keep her temper, and Marmee confides in Jo that she, too, suffers with this same affliction. It is only because of Mr March’s patience with her, she tells her daughter, in reminding her to silence herself her when she is in danger of boiling over, that she has managed to curtail this unwanted element of her personality.

This is difficult to assimilate, especially when it is precisely Jo’s rebellious, headstrong nature which endears us to her as female readers. It occurred to me as I re-read that Alcott has put into her novel all the love she felt for her three siblings and her mother, whilst attempting to deal with the ways in which her father, even in his absence in the book, controls their feminine impulses.

On returning to the novel, what I noticed as an adult was a lot more piety than I remembered, and it occurs to me that although we remember Jo March as a feisty and independent version of Louisa May Alcott, essentially throughout the novel, Marmee and others are countenancing all four girls’ independent spirits by telling them what ‘good little women’ they should be. To want for anything extra, or to have dreams and ambitions for their lives for anything other than marrying a good man and having a family of their own, feels like anathema to their father away fighting, or their mother ceaselessly giving her time to the poor and bereft of the town.

There are repeated episodes within the book where the girls are admonished or ‘taught’ lessons by their mother on how they should think, feel and behave as appropriate young women. Although ‘Marmee’ is portrayed as a kind and loving mother who only wishes the best for her young daughters’, attempting to guide them with a loving and generous hand, she is also aware of the natural order the girls’ lives are likely to take.

I did begin at this point to resonate a little more with Gerwig’s wish in her film version to assimilate some of Alcott’s political views and personal experience.

Alcott also appears to have been deeply influenced by the men of her father’s circle, particularly Emerson, whom she referred to as “the god of my idolatry,” and attended his discussion group on occasion, when invited. In fact, she idolised many male writers, and this was perhaps to her own great cost, leading to her inhibitions of her own talent as a writer.

“I will do something by-and-by. Don’t care what, teach, sew, act, write, anything to help the family; and I’ll be rich and famous and happy before I die, see if I won’t!”

In the story of the March family, reference is given to Mr March’s loss of fortune, meaning the two eldest girls, Meg and Jo, must work to help out the family finances. They have no money for fancy ball gowns to attend nice dances given by richer friends, something which causes Meg much disquiet. Mr March meanwhile appears a distant character who is not to be blamed for his loss of fortune.

Elaine Showalter claims that Alcott’s only independence from her loving but all-consuming family was in her writing. She would engage in this “vortex” of creativity whenever she felt the need (as does Jo in Little Women, losing all track of time as she sits eating apples and penning her stories below the eaves of the attic room).

Alcott was born the second of four sisters: Anna, Elizabeth, and Abigail May (known as May). She based her four ‘little women’ on her love for her siblings. She uses many themes from their lives in her famous novel, including the death of her beloved sister Lizzie (befalling this in the March family to Beth) and the marriage of her older sister and closest confidante Anna to a neighbour (consigning Meg to Laurie’s tutor, John Brooke). Her own feelings on marriage, sexuality and love appear to have been somewhat conflicted and ambivalent. She confessed in one interview that:

“I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body…because I have fallen in love in my life with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man.”

Alcott wrote many essays contemplating the idea of a single life for a woman, as well as communities of female artists and professionals, and often criticised early marriage for young women:

“Half the misery of time comes from unmated pairs trying to live their legal lie decorously to the end at any cost.”

As Elaine Showalter suggests however, she did attempt to show the possibility of strong and loving marriages in her book, whereby both partners respected one another’s creative and intellectual lives and worked together as equals. Perhaps this can be recognised with the eventual pairing of Laurie and younger sister Amy, who works hard at her painting and is an accomplished artist, of which Laurie admires.

As Showalter further affirms, it is impossible to know whether Alcott had any sexual orientation towards women which entailed her avoidance of marriage, or whether it was simply that she felt her independence threatened by the idea of wedlock.

Alcott published many stories, poems, and essays during a ten year period of steady writing, along with other work pursuits of teaching, sewing, and as a domestic servant. She worked hard to contribute to her family as well as continuing to work on the writing that she loved. However, it was during her thirtieth year when her writing suddenly took a more lucrative turn.

Volunteering in 1862 as a nurse in the Civil War army hospital in Washington, she contracted typhoid fever after only six weeks. During those six weeks however, Alcott experienced a level of independence away from her family that she had never known before, and I wondered as I read of Jo’s escape to New York to write, whether in fact this was Alcott’s way of channelling those desires in herself. Despite a tour of Europe and a couple of brief trips to New York, Alcott lived and died in Concord, the place she grew up in.

Writing a book about her experiences in 1863, Hospital Sketches, during the next few years, she finally began to make enough money from her writing that she could give up her other work. Writing under different pseudonyms, she crossed various writing modes, such as ‘Flora Fairfield’ for her more ‘feminine’ writing, and ‘Minerva Moody’ as a humorous dig at her more serious and intellectual writing.

She also at this time began secretly writing lurid thrillers under the pseudonym “A.M. Barnard.” These stories contained many imaginative plots based around forbidden topics such as incest, adultery, and violent revenge.

“I think my natural inclination is for the lurid style…I indulge in gorgeous fantasies and wish that I dared inscribe them upon my pages and set them before the public.”

In September 1867, a partner in her Boston publishing house, Thomas Niles, requested that Alcott write a “girls’ story.” Alcott didn’t immediately agree, but was further encouraged to do so the following year by her father, who had been in touch with the publishers, hoping they would take his book of transcendental essays. Alcott was reluctant, claiming that she never really liked girls, other than her sisters, and doubted that their experiences would prove interesting in book form.

The term “girls’ story” essentially meant a moralistic tale meant to encourage marriage and obedience; not exactly in line with Aclott’s tales of violence and revenge. Alcott had in fact been contemplating writing a novel about the family’s misfortunes around her father’s visions, however she instead decided to cast Mr March as a soldier in the Civil War and write about her sisters, beginning one Christmas as the girls gather together gifts for their overworked mother.

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.”

Following along the course of a year in the girls’ lives, Alcott decided to write the book as a parallel of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, attempting to revise Bunyan’s text as an exploration of women’s experience. This is made evident throughout the book, which begins with Marmee gifting a copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress to each of the girls for Christmas, and with the first chapter of Little Women entitled “Playing Pilgrims.” The story then follows each of the sisters’ through various trials and misfortunes, as they grapple with becoming impoverished and trying to learn how to be ‘good.’

Alcott ends the first book with Mr March’s return from the Civil War the following Christmas.

Niles was happy with what she had written, although asked her to write another chapter, ending with a suggestion that there may be more to come from the March sisters. This she did, alluding to the future and announcing the engagement of oldest March sister, Meg. Alcott responded to his enthusiasm, claiming that she found her work: “not a bit sensational, but simple and true, for we really lived most of it.”

Although claiming that it was not a ‘sensational’ novel, Alcott still manages to inject some of her own personality and penchant for the lurid, violent stories she loved to write. She gives Jo the pen to create such works herself, and has her act out the male roles in the sisters’ plays and performances, full of murder, rage, and witchcraft. The March sisters’ even create their own literary ‘men’s club’ in which they take on the identities of Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Club members.

On first publication in 1868, Little Women became a huge success, and at the behest of her publisher, Alcott began writing a sequel. For her part, she stated that she did not much like sequels, and felt that the book would not do as well as its predecessor. She was disappointed by the letters she received from young girls asking whom the sisters’ would grow up and marry, “as if that was the only end and aim of a woman’s life.” She thus resisted the pressure to marry off Jo as long as she could, but her publisher continued to pressure her, and whilst sticking to her initial principles of not allowing Jo to marry Laurie just to please her audience, she decided she could make a different kind of marriage plot for her heroine. She claimed in a letter to a friend that, exasperated by the clamouring of readers to marry her off to Laurie and her own feeling that Jo should remain a literary spinster, she decided on a funny match for her, allowing her to accept the proposal of the middle-aged German professor, Friedrich Bhaer. But apart from this being ‘a funny match,’ it is also true that Jo’s marriage to Bhaer is an attempt by Alcott to reconcile the idea that a marriage could be a supportive, intellectual arrangement.

The second book closes on Marmee’s sixtieth birthday as the family gathers to celebrate. Jo has matured from a fifteen year old girl in the first book, to a thirty-five year old married mother, who runs a school for boys with her husband in the large estate left to her by her old Aunt March.

Despite her earlier concerns, Alcott’s second book went on to be a success, and by the end of 1869, she had made $8,500 dollars in royalties. She could finally put the family’s financial burdens behind them, and her father appeared to be proud at last, rather enjoying his celebrity status as “The Father of Little Women.” She was now a much sought-after writer and continued to write many more novels and short stories, although it is for Little Women, the book that she was reluctant to write and which she based on the lives of her own family and her sisters’ adventures in growing up, that would make her a recognisable name. It was also the novel that many young girls growing up would turn to to recognise their own rebellious nature in the form of Jo March.

Returning to Little Women with more knowledge of the life and familial circumstances of its author helped to put the sometimes pious aspects into perspective. Overall, as soon as I read the first line of the book (which I know off by heart) I remembered the way I had felt when I first encountered Jo March. She was just as winsome and wonderful as I remembered, and the whole reading experience left me with a feeling of warm nostalgia and recognition.

One of my favourite scenes sees Jo meeting ‘the Laurence boy’ at a dance, where she is hiding behind a curtain, lest anyone notice the huge scorch mark at the back of her dress, from standing too close to the fire. When she confesses that she would like to dance, she and Laurie make merry along the hallway behind the curtains, enjoying themselves immensely. I remember wanting to have that much fun and embodying that carefree spirit of Jo March. As a child who was always tripping, spilling, or otherwise ruining my clothes, I also resonated with Jo’s clumsy nature.

In the end though, what I realised most through my reread this December, is that what makes a book special is not necessarily that we agree with every word on every page, or that it is the best story in the world, or that it stands up to the test of time.

What remains with us of our very favourite books are the feelings we have when we think of them. Of the emotions they spark. They are tied up in the memories of our first encounter with a book and everything that has followed; the people we have become.

In my case with this book, it is the sense of safety of my mother tucking me into bed at night, sitting and reading from the book. It is sharing the films, every single Christmas of my childhood and beyond. It is debating which actor plays the best Jo March (she was right: it is totally Hepburn). And it is sharing that now with my own grown up daughter.

It is the warmth, the safety, the whole idea of childhood and growing up and becoming a writer and having a community of women to show us the way.

How remarkable that a book could engender all that and more.

Do you have a book that does this for you? A story you come back to again and again? I’d love to hear about it in the comments 🙂

Thank you if you’ve read this essay all the way to the end- it was a bit of a long one, but there was so much more I could have written about this book and the author! If you’ve found yourself here and like what you see, please consider subscribing, so you don’t miss another literary discussion.

Joanna Biggs, A Life of One’s Own, (2023), W&N:London.

Elaine Showalter, (ed.), ‘Introduction,’ Louisa May Alcott, Little Women, (1989, [1868]), Penguin:London. (All further quotations from this Introduction).

Louisa May Alcott, Little Women, (1989, [1868]), Penguin:London. (All further quotations from this edition).

Lovely! (I have to admit that I loved the Gerwig adaptation. Though I haven't seen the one with Hepburn.)

I loved this. Thank you. I remember reading an abridged version when I was quite small - it had line drawings in it, and I remember colouring the pictures in! I loved the 'Americanism ' of it, and how it seemed so far removed from growing up in the UK. All the snow, and skating on the ice, house parties and 'boys next door', Daddy away at war, and their make do and mend attitudes. I do remember the piety - I remember vividly even now their gifts of The Pilgrim's Progress and the descriptions of the different coloured covers. Gosh, you sent me back in time!