Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

This essay forms part of ‘The Joan Didion Project’, set up and co-ordinated by my excellent Friend in Reading,

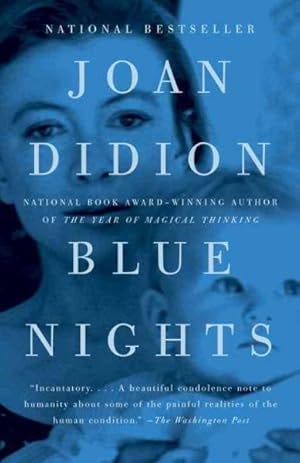

on The Reading Life. Please check out her wonderful newsletter for more on this project, as well as just because she is a pretty awesome individual 🙂In Lauren Sandler’s 2013 piece for The Atlantic, ‘The Secret to Being Both a Successful Writer and a Mother: Have Just One Kid’, she responds to Didion’s 2011 text, Blue Nights, advising that writing about the adoption of her only child Quintana Roo was a text that Didion avoided tackling during her prime writing years.

In 2005, Quintana, then aged just 39, sadly lost her life. In Didion’s earlier book of creative nonfiction, The Year of Magical Thinking, she speaks about the year following her husband John Dunne’s death and her struggle to come to terms with her grief. She tells us that, on the evening of his death, they had just returned home from the hospital after visiting a gravely sick Quintana. For Didion to then lose her daughter just a year and a half later, after a series of illnesses, was unthinkable.

But rather than write another meditation on grief and the ways in which we try to placate ourselves, in true Didion style, she makes this book about so much more than that.

The text - named for the time of year when the light begins dwindling over New York City - deals with both the life and death of her daughter; the experience of caring for an adopted child; her questioning of her own role in her daughter’s struggles; memories and their limitations; and the realisation that she is ageing into ill health whilst outliving her whole family.

But there is an overarching theme to this whole book: Fear.

“Once she was born I was never not afraid.”

Didion explores the overwhelming fear felt by not just herself, but parents in general. She refers to mortality as being the total realisation as a parent that you have the constant worry for your children; for yourself as the gatekeepers of their safety; and for your own mortality, should you leave them needing you.

“When we talk about mortality we are talking about our children…The source of the fear was obvious: it was the harm that could come to her.”

Joan and husband John adopted a newborn baby girl when Joan was 31 years old. She already had a hugely successful career established by this point, and although she puts across their absolute wish to adopt the baby girl, she confesses that the reality of doing so so soon after enquiring about adoption was still not something she fully comprehended. Speaking about her sister-in-law’s offer to take her shopping to Saks in order to purchase a bassinet before picking up the newborn, for example, she states:

“Until the bassinet it had all seemed casual, even blithe, not different in spirit from the Jax jerseys and printed cotton Lilly Pulitzer shifts we were all wearing that year.”

The year in question was 1966; the American military presence in Vietnam was to exceed 400,000 soldiers that year, and Joan and her husband were scheduled to fly out on assignment.

“It was not widely considered an ideal year to take an infant to southeast Asia”, she tells us, “yet it never occurred to me to adjust the plan. We had assignments from magazines, we had credentials, and we had everything we needed. Including, suddenly, a baby.”

The trip was eventually cancelled - though not due to the sudden arrival of their daughter, but because of a deadline for John’s next book. But if this serves to give the impression that Didion had a blasé attitude to her role in Quintana’s life, her text puts this idea to bed. In fact, it would seem, nobody could lay the blame at Didion’s door for the ways in which her daughter’s life ended so tragically as harshly as Didion did herself.

She speaks as though she herself cannot believe the juxtaposition of her thoughts, fears, and actions at the time she adopted Quintana and during her childhood. In her text, she moves seamlessly between scenes of Quintana’s wedding day, her daughter’s childhood, her daughter’s friendships. This is no linear remembrance. Didion uses repetition to great effect in the book: the questions she has for herself as she comes to terms with her grief appear throughout, as I imagine they appeared on repeat in her consciousness at this time.

“Dreaming in other words that I had failed. Been given a baby and failed to keep her safe.”

She appears to be fighting with her own memories on child-rearing within this narrative: on the one hand, she speaks of the ways in which children were brought up in her own childhood, during WWII, almost as a way in which to ‘defend’ her often seemingly ambivalent attitude to motherhood. On the other hand, she exposes the dawning realisation that her own daughter’s life, amongst celebrities and film stars, was not the accepted norm.

“It was a time of my life during which I actually believed that somewhere between frying the chicken to serve on Sara Mankiewicz’s Minton dinner plates and buying the Porthault parasol to shade the beautiful baby girl in Saigon I had covered the main “motherhood” points.”

She speaks about the often strange circumstances of her daughter’s childhood as though excavating them for the first time. She tells of Quintana accompanying her parents on location on film sets, including the time a babysitter asked Quintana to get Paul Newman’s autograph for her, causing her daughter a stress she was too young to deal with. Or the time Didion took Quaintana on a book tour with her to several cities, where she says Quintana learned to order room service for her own Shirley Temples. This, Didion is acutely aware, conjures a life of ‘privilege’, something which she finds difficult to assimilate when she considers the trajectory of her daughter’s life.

She is also preoccupied throughout the text by her fear and worries around her ‘suitability’ as a parent, particularly one entrusted with the care of an adopted child.

“Those of us less inclined to compliment ourselves on our parenting skills, in other words most of us, recite rosaries of our failures, our neglects, our derelictions and delinquencies.”

She is clearly in a constant torment whilst writing this book as to her competency in raising a young and often troubled child, who grew into a young and troubled adult. She speaks of Quintana’s overwhelming abandonment issues, stating that:

“Adoption, I was to learn although not immediately, is hard to get right.”

Her comments on the accepted “narrative” at this time on how to deal with adopted children and the stories we tell them about their provenance is candid and openly questioning; looking back at the adult nature in which Quintana conducted herself as a child, she appears to be constantly questioning her own part in this.

Lauren Sandler in her article picks up on Didion’s inclusion in the book of a list her daughter pinned to the garage door, “Mom’s Sayings”, which included: “Brush your teeth, brush your hair, shush I’m working.” This, Sandler says, became ‘evidence’ of Didion’s maternal negligence in reviews of Blue Nights. But Didion must have anticipated such reviews, because the evidence of how she worried over these and other memories are laid out in painful exposition in her book. Whether accurate or not, Didion did not require the judgement of others on her perceived good or bad parenting: she was already grappling with this in her own words.

“Was I the problem? Was I always the problem?”

Sandler also queries whether John and Joan’s intensely close relationship was something which Quintana perhaps struggled with the most; that the pair were one another’s editors and first readers, sharing an office and their consuming passions, which perhaps led to their daughter’s feelings of exclusion.

“Had she no idea how much we needed her?”

Whilst this may be so, I can’t help but warm to Didion’s comments on her style of parenting: who amongst us has not felt that we could have handled a situation with our children better?

When I read the thoughts that crowded Didion’s mind as she contemplated the future without her daughter: the questioning of her mothering, the reflections on her refusal to see the problems her daughter was grappling with, her insistence on continuing with her successful career as a writer, and so on, I couldn’t help but think of all the times I have felt that I have ‘failed’ as a mother.

These are the kinds of thoughts that can crowd a cluttered mind in the early hours of the morning, wondering: if, when, how, our thoughtless comment or misunderstanding could have affected our offspring’s psyche and interactions with the world. How this might follow them into adulthood.

When it later became clear that Quintana was more fragile than anyone had realised, after John and Joan had taken her to various medical professionals, enduring suggested diagnosis after diagnosis, she was declared to be suffering with a “borderline personality disorder.” This, Didion felt, was the one diagnosis that seemed to most closely apply.

“How could I have missed what was so clearly there to be seen?”

However much questioning Didion does around the part she played in Quintana’s childhood, I think she comes to the realisation that her daughter’s fear of abandonment due to adoption and her possible personality disorder were already present, regardless of her upbringing. Whilst she confesses that she missed or refused to see the signs as her child developed, she also struggles after her daughter’s death to look at the photographs and memento’s of her life without seeing them in obvious, sharp relief.

Didion also relays the story of Quintana’s birth sister tracking her down, and her subsequent meeting with the extended members of her birth mother and family. She writes about this in the usual Didion-esque way: the scalpel-prose, the journalistic viewpoint. Like she is a bystander, examining a piece of information and assimilating it neatly for our consumption. Like the way she related the shocking discovery of a five-year-old drug addict in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. But it is clearly an occurrence that she struggles to maintain equanimity around.

I wanted to write deeply about this book based on my re-reading experience. About mothers and daughters and parenting and ageing. I fear I have not done the book justice on any of these accounts.

I jumped at the chance to revisit the book when Petya announced her project: I remembered finding it beautifully written, and felt that returning to it now, with an adult daughter and a teenager as I sit around my middle years would be an interesting experience.

But I found this book much more difficult to read this time around.

Perhaps it is as, since first reading, I now have an adult daughter myself, have lost people I loved, and have made many parenting and other mistakes along the way. It is perhaps also the new understanding, through Didion’s words and her obvious pain in this book, that when things fall apart, it is difficult not to blame ourselves.

Reading Didion’s words brought home to me how memories are fleeting. How our questioning of the ways in which we parent our children are forever close to mind. And of how the fear of our mortality, through the experiences of our children, never really goes away.

Free subscribers receive my weekly researched essays every Sunday, as well as access to community threads.

Paid subscribers also receive access to my monthly reviews and full archives. A paid subscription works out at less than £2 per month for the yearly fee, helping me to research and celebrate the important words of women.

Thank you for your support 🙂

Blue Nights was one of the first memoirs I read when contemplating writing one of my own. It has stayed with me to an almost shocking degree. I just can’t get over the sheer audacity and bravery of laying herself bare over such a shattering personal loss, and on top of that using it as an opportunity to publicly excavate her own perceived failures at parenting. Besides which, it’s a gorgeous book. Every new revelation is devastating, yet I couldn’t deny the pure pleasure of reading her beautiful sentences.

Thank you for this essay. I finished this book a couple of weeks ago and am still mulling things through, feeling I don't have much -- or rather not enough and not the right things -- to say. Motherhood either sinks under its idealized visions or is torn to shreds by criticisms of real mother's words and actions. The difficulty of writing about it without falling into either extreme is palpable. And, of course, Didion's pain leads her to the latter -- at times her self-questioning is difficult to bear. The reader wants to comfort her but it's impossible, of course.