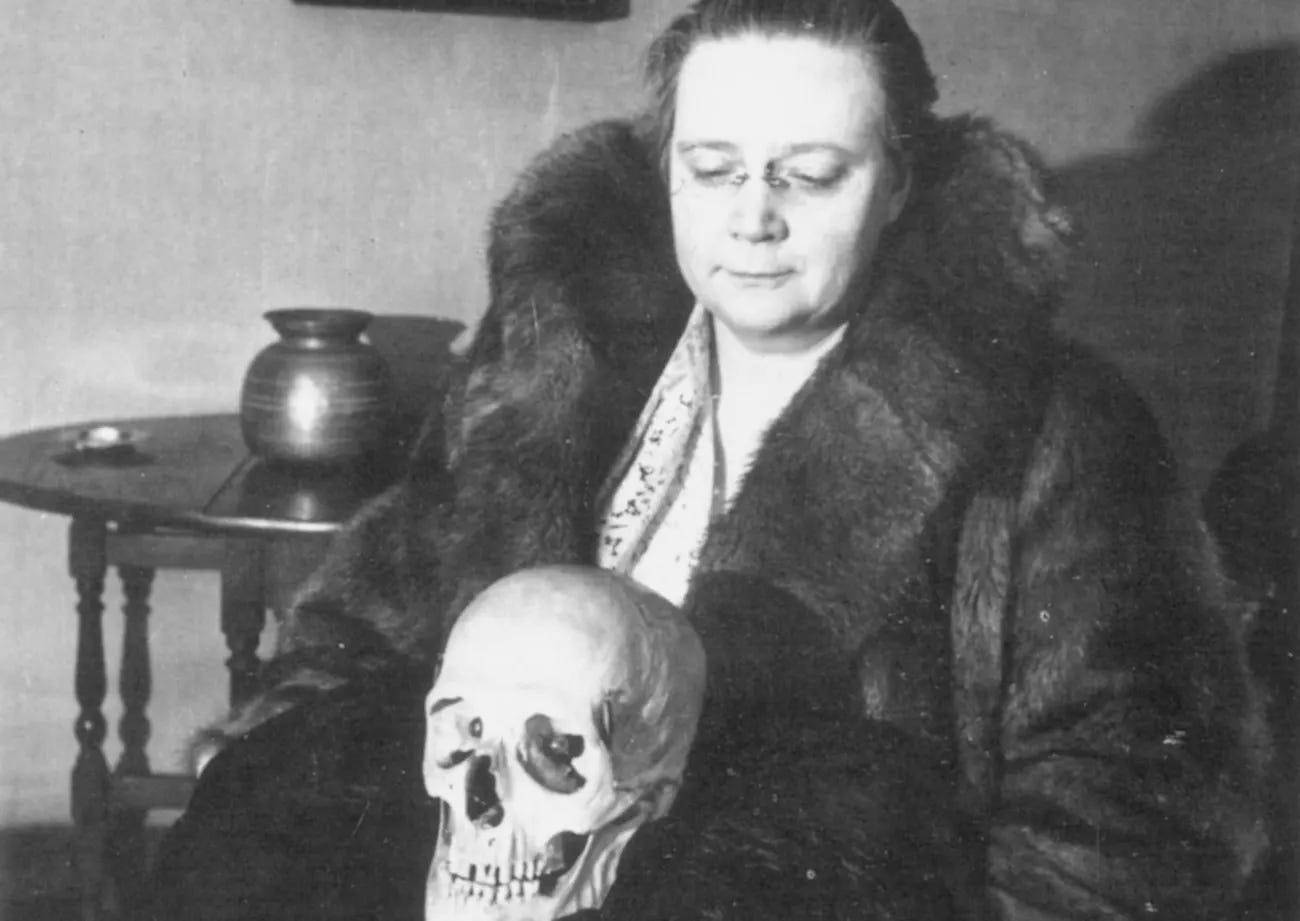

Dorothy L Sayers & the Detection Club

On the friendship & personal tragedies of an indomitable writer

‘She was not born a feminist; she became one’.

Agatha Christie is inarguably the most well-known female author of detective fiction, as well as a successful playwright and short story writer. Known for being shy and introverted, Christie nevertheless benefited from an enduring friendship with another of her contemporaries, Dorothy L Sayers (I have written before about the friendships of female writers, and this is a subject I may turn into a series, as it is something which continues to fascinate me!)

The two women, whilst sharing a love and talent for writing detective fiction, had somewhat different upbringings. Whilst both women were educated at home, Christie’s parents purportedly educated the young girl in the hope of preparing her for marriage. Sayers however, who was also educated at home, was prepared for Oxford by a rigorous education schedule instigated by her ambitious parents. The daughter of an Anglo-Irish Reverend and brought up at Bluntisham Rectory in Cambridgeshire, Sayers did indeed secure a scholarship to Somerville College, Oxford, graduating in 1915 with first class honours in modern languages.

Whilst taking various jobs following her graduation from Oxford, including many in the advertising industry, Sayers returned to academia later in life, completing a translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy, something which she considered as the pinnacle of her career.

In 1923, Sayers published her first Lord Peter Wimsey detective story, Whose Body, going on to write fourteen novels and short stories around her most famous character. It was her creation of detective fiction based around the amateur sleuth which was to make her a recognised name, as well as secure her friendship with Christie.

Both women were members of the Detection Club, a group of leading crime writers who met regularly to socialise and discuss their writing. The Club had an initiation policy, ensuring that all members abide by a strict set of literary rules which were ultimately designed to give the reader of their work a fair chance of guessing the culprit within their detective fiction.

Members of the group also worked jointly on writing projects, and Sayers took an instrumental role in such activities. Christie, meanwhile, merely fitted in, and it was reported that when she was made president of the Club following Sayers’ departure of the role, she agreed to the position only on the condition that someone else chaired the meetings and gave speeches.

In fact, it was Sayers who was also the power-house between the pair when recording their various collaborations and radio plays, with herself being the one constantly having to track Christie down. Whilst being a fan of Christie’s writing, BBC producer J.R. Ackerley was said to have referred to Christie as being a ‘little on the feeble side’ when it came to broadcasting, whilst he conceded that ‘anyone in that series would have seemed feeble against the terrific vitality, bullying and bounce of that dreadful woman Dorothy L Sayers’, underlining the chasm in the two writers’ personalities.

Christie must have felt some affection towards working with Sayers however, as being the more successful of the two novelists, Christie earned far more from other writing work. In return, it was Sayers who involved herself in the search for Christie in 1926 during her well-documented ‘disappearance’. She further defended her friend when other members of the Detective Club tried to expel her, citing Christie’s ‘unfair’ plot within her novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

Due to Christie’s shyness and introvert tendencies, she reportedly had few female confidantes. Her friendship with the indomitable Sayers however endured, providing an important working relationship throughout the two women’s successful writing careers.

Sayers meanwhile had an interesting and secretive personal life, which some have said fed into the intensity of her writing.

In 1920, Sayers embarked on a passionate but unconsummated relationship with imagist poet John Cournos. The couple broke up after two years, however, as Cournos insisted on consummating their relationship using birth control, as he was against marriage and children. Sayers however would not agree due to her religious beliefs. Cournos also claimed to see detective writing as low brow, a double blow to Sayers when upon his return to New York, he quickly met and married a female detective fiction writer whom already had two children.

This left Sayers embittered, claiming in heated letters that he had tested her own moral principles whilst disregarding his own. Cournos in return claimed that he would have married Sayers, had she committed to a sexual relationship with him. The pair eventually responded in more amicable terms following Sayers’ own marriage to Atherton (“Mac”) Fleming, a Scottish journalist.

Strangely, given her upholding of strong religious beliefs, Sayers quickly embarked on a rebound relationship with William (“Bill”) White, a car salesman. On discovering herself pregnant, however, William bolted, leaving Sayers to consider her limited options as an unmarried, pregnant woman in the 1920s.

Remarkably, help came from the most unlikely of sources. On discovering her husband’s actions, White’s wife arranged for Sayers to give birth secretly in a nursing home in Southbourne. A few days before the birth, Sayers finally broke silence, writing to her cousin Ivy who was at that time a foster parent. Sayer’s son, John Anthony White, was left in the care of Ivy, who kept Sayers’ secret.

It was suggested that Sayers had hoped that she and Fleming could have John come and live with them following their marriage, but despite visits to cousin Ivy’s to see the boy, Fleming was not keen on the idea, and she reluctantly agreed it was impractical given both their careers as writers and their small flat.

Though continuing to visit her son and keeping in contact with him, as well as sending financial support over the years, her true connection to John was only revealed following her death in 1957. John was the sole beneficiary of her will and inherited her estate.

Though Sayers’ novel Gaudy Night has been described as the first feminist mystery novel, she distanced herself from feminist political labels, preferring to be considered ‘simply human’. She has been referred to as preferring to practice women’s rights rather than preaching them, and academics have gone on to identify her as a feminist, with scholar Susan Haack claiming that she ‘was not born a feminist; she became one’.

Though Sayers’ experience of motherhood and the personal difficulties this brought her in regard to her Christian faith were troubling throughout her life, her writing career was a satisfying success to her.

Finally completing her last Wimsey novel, Gaudy Night, she was persuaded by a friend to collaborate in a stage play featuring the detective called Busman’s Honeymoon. First appearing in 1936, this was a success, ensuring that Sayers could give up crime writing, other than a book version of the play and three short stories. Now gaining financial security, she turned to the work of playwriting, for which she had a fond fascination, and to putting to use her training in classical and modern languages.

Sayers began with a play for the Canterbury Festival, The Zeal of Thy House, and went on to write six further plays, with the most prestigious being The Man Born to be King, commissioned for appearing in the BBC’s Children’s Hour. Within it, she features the voice of Christ speaking modern English which raised outraged protests and subsequently went on to revolutionise religious play-writing.

Sayers appeared to thrive on such opposition to her work and did not allow her art to be compromised by dissenting voices. She also thrived on using her traditionally Anglican theology instruction, spending all her time working on her writing, which included essays, literary criticism and letters. Her immense wit and formidable presence, as well as her enjoyment of debate, led to her becoming in great demand as a lecturer, and eventually to her becoming churchwarden of her London parish of St Thomas-cum-St Annes in 1952.

Teaching herself old Italian following the war, she began work on her magnum opus: the translation of The Divine Comedy, receiving praise for its unmatched clarity.

Sadly, Sayers died of heart failure in 1957 before completing Dante’s third volume, Paradiso, and her friend Dr Barbara Reynolds completed her work on this. She had worked to the end on her true passion, and had managed to forge a successful career as a writer, despite her own personal struggles.

Her death bestowed on her shy old friend Agatha Christie the Detective Club’s presidency, further cementing the friendship and respect the two women held for one another, and which both had drawn on for support throughout their writing careers.

Whew! I love Sayers’ work but I had no idea what a complicated and compassionate life she had. I love learning from your writing!!

This is a really well written piece. I love crime fiction, especially if this era, and the insights and quality research really make me want to read more by Sayers.