Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture. If you value the work that goes into writing this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber today. Your support makes this work possible.

Last week, we looked at the ‘waves’ of feminism, from the first-wave feminists fighting for the right to vote, through the second-wave in the 1960s and 70s who were looking for liberation and autonomy, to the third- and fourth-wave feminism of today.

This week, I want to consider the Black feminist movement.

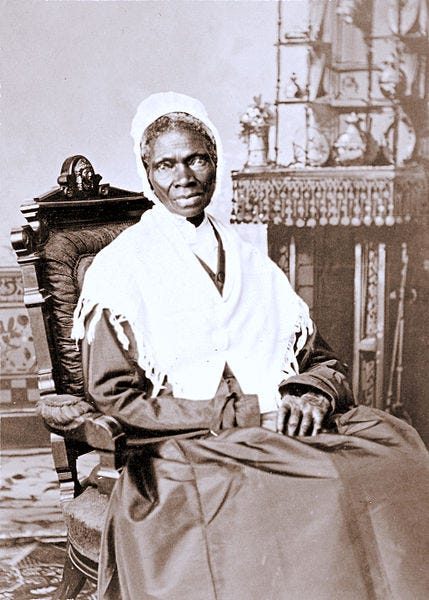

No discussion of Black feminism can exist without a consideration of Sojourner Truth, born into slavery in 1797 as Isabella Baumfree, she escaped to claim her freedom in 1826 and spent the rest of her life advocating for equality for all, changing her name to Sojourner Truth.

Truth suffered the indignities of slavery including being denied marriage to a fellow slave whom she loved and instead forced to marry another, with whom she birthed five children. In 1827, Isabella Baumfree ran away after her master refused to uphold the 1827 New York Anti-Slavery Law. As she later informed her former master: “I did not run away, I walked away by daylight….”

Isabella later experienced a religious conversion, and became an itinerant preacher in 1843, changing her name to Sojourner Truth.

Truth became involved in the growing anti-slavery movement, and by the 1850s was involved in the women’s rights movement. Her 1851 speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” specifically targeted the lack of recognition of Black women in the conversation around equal rights and a more just society.

Truth continued to fight for both the rights of women and African Americans throughout the rest of her life, until her death in 1883.

Black British feminism had its roots in postcolonial activism, and the struggles felt by migrant women from former colonies in the Caribbean, Africa, and the Indian subcontinent. These women had come across to Britain in the post-war recruitment drive of the 1940s and 50s, often known as the Windrush Generation.

Forceful voices within the Black women’s movement included Claudia Jones, whom I wrote a biography about last year, and who campaigned extensively for the rights of women and men, particularly those of a lower economic class.

Stella Dadzie, a feminist pioneer of the Black British movement, co-authored a seminal text The Heart of the Race in 1985 which quickly became a feminist classic. The text explored, amongst other concerns, racism in schools and police brutality. She documented the lives of Black women in Britain, alongside another feminist pioneer, Olive Morris, together founding the feminist and anti-racist group, Organisation for Women of Asian and African Descent, in 1978. Raised by a single mother in 1950s Britain and experiencing extreme poverty and discrimination had a direct effect on Dadzie’s ability to campaign for the dispossessed and the underdog.

In the US, no discussion on the Black feminist movement can be separated out from the civil rights movement, and one of the chief criticisms of second-wave feminism was that it often left out the needs of women of colour. It also often focused on the effects of sexism on the middle-class woman, rather than consideration of the needs of working class women. Many of the most outspoken members of the white women’s movement spoke of “unity” within the movement only once they had gained recognition for the cause. This idea meant that women of colour were expected to put their own concerns on hold whilst the movement gained traction.

The term ‘intersectionality’ was not coined until 1989, after the second-wave feminist movement, however women of colour were forming feminist political activist groups throughout the 1970s. The white feminists were often seen as ignoring the extra difficulties faced by their Black counterparts, negating the factors of race and class for such women.

The Combahee River Collective formed in Boston in 1974 and drew on the women’s experiences in Black, male-dominated organisations, where they had often felt left out and their experiences as Black women ignored. They similarly felt ignored by the feminist movement, led by predominantly white middle-class women, who they felt struggled to assimilate the reality of life for Black women, where many worked outside the home, raised children alone, and faced extreme poverty.

These women, as well as facing down the patriarchal system, had to contend with a racist society. They saw the unjust assumption that white women were encouraged to prioritise their families, whereas Black women who relied on welfare to take care of their children were seen as freeloaders. Whilst many white women of the feminist movement were focused on raising awareness around abortion rights, the Collective argued that women of colour were fighting against the forced sterilisation of women of colour.

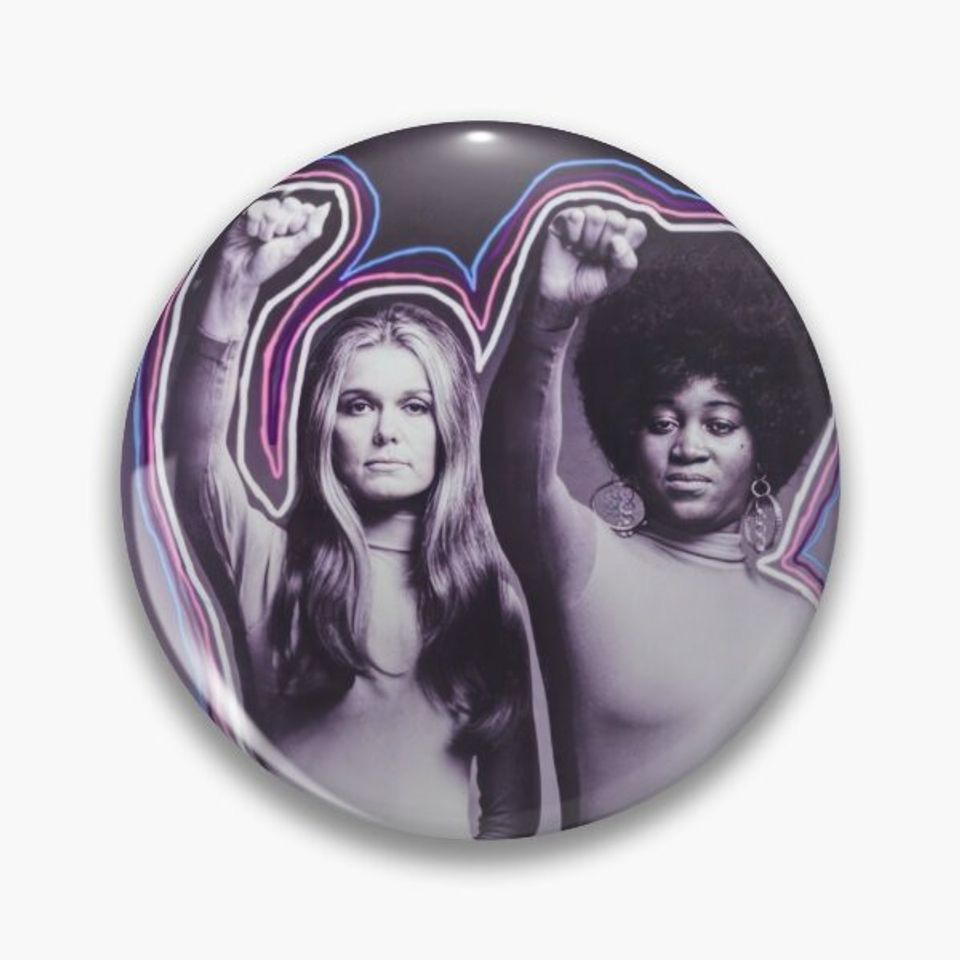

One of the most recognisable Black US feminists of second-wave feminism came in the form of Dorothy Pitman-Hughes, a community activist who co-founded Ms magazine with Gloria Steinem and who appeared alongside one another in perhaps one of the most iconic photographs of second-wave feminism. Both women show their raised right arms in the Black Power salute. The original, taken in 1971, now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC.

Hughes and Steinem became powerful spokeswomen for the cause in the early 1970s, touring the country and challenging the belief that feminism was for white, middle-class women. Despite Steinem being perhaps the more famously recognisable feminist speaker, she credited Hughes with giving her the confidence to speak publicly.

Hughes was born Dorothy Jean Ridley in Georgia in 1938. At ten years old, her father was beaten to death and left on the doorstep of their family home; the murder was believed to have been carried out by white supremacists with the Ku Klux Klan.

Moving to New York in the late 1950s, Hughes worked several jobs, including in retail, as a nightclub singer, and as a house cleaner. But by the 1960s, she had begun working alongside Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X as part of the civil rights movement.

“The most neglected person in America is the Black woman.”

Hughes saw priorities in the provision of affordable childcare for Black women who needed to work, leading to her setting up the West 80th Community Childcare Centre in 1968, which was where she met Steinem, who was already working as a journalist and writing a story for New York Magazine. The two became firm friends and spoke across the United States on gender and race issues between 1969 and 1973. They co-founded Ms Magazine in 1972, a magazine centred around women’s empowerment, featuring Wonder Woman on their first front cover.

One of Hughes’ greatest contributions to the feminist movement was to help entire families who attended the community centre. She often helped families out of homelessness, giving them jobs, and assisted them in improving their lives. Unlike some of the central figures of the white women’s movement, Hughes recognised that the challenges of affordable childcare were deeply enmeshed in issues around racial discrimination and poverty.

Hughes’ biographer Laura L Lovett wrote in Ms that Hughes “defined herself as a feminist, but rooted her feminism in her experience and in more fundamental needs for safety, food, shelter and child care”. She wasn’t afraid to call out the racism she saw in the white women’s feminist movement and often spoke out about the way the white women’s privilege oppressed Black women, whilst displaying that this could be overcome through her enduring friendship with Steinem.

So where are we now with the issue of Black feminism and are there still echoes of separation within the movement?

There are many current examples of Black women who are leading the way in the fight for equality. Tarana Burke founded the “Me Too” movement in 2006, in an effort to support survivors of sexual abuse, particularly young women of colour. The perhaps more well-known “#MeToo” movement of 2017 was inspired by Burke’s 2006 movement, and has gone on to become an unprecedented force in the fight against sexual violence and abuse.

Other inspiring women of colour working within the movement include Vanessa Nakate, who works to amplify African voices within climate justice, and Jaha Dukureh, who speaks out about FGM practises after being victim to the procedure, as well as a forced marriage at the age of 15. Whilst Emanuela Paul, a feminist activist from Haiti, works with Beyond Borders, working to prevent violence against women and girls, in particular those with disabilities.

Unity Dow, after becoming Botswana’s first female High Court judge, has been successful in, amongst other women’s and human rights issues, challenging the Botswanan law preventing Botswanan women conferring their nationality to their children where their chosen partner is a non-citizen. And in Brazil, Valdecir Nascimento mobilised more than 10,000 Black women in a march calling an end to violence and racism and raising their demands for gender equality.

These women are continuing the work of the Black feminist movement and are embodying the unifying culture of Intersectional feminism.

The term ‘Intersectional Feminism’ has been the buzz-word for an increasingly inclusive feminist movement in the past few years. The term emerged in 1989 and came from lawyer, civil rights advocate, and intersectional feminist Kimberlé Crenshaw, who claims it is “a prism for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other.” She goes on to explain that “All inequality is not created equal”, and that an intersectional approach shows the ways in which people’s social identities overlap, which creates a compounding experience of discrimination.

Some people are therefore more susceptible to discrimination and unequal treatment due to various facets: they may be discriminated against due to their race, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, class, socio-economic status, and so on. Many people will fall into more than one of these overlapping categories, meaning they experience concurrent forms of oppression. Intersectional feminism recognises this and puts the voices of those experiencing such overlaps at the centre.

Intersectional feminism matters as many people feel they are ignored on the margins within global issues. Many communities face interconnected issues, as did the pioneering voices of the Black feminist movement such as Hughes, who recognised that Black women’s needs were often practical ones of affordable childcare whilst they tried to support their families. Their interconnected issues were ones of not only gender, but race, poverty, and often homelessness, amongst many others.

Adopting the principles of Intersectional feminism allows for a culture of equality for all women and self-identifying women, regardless of race, colour, class, gender, disability, or sexual identity. In an increasingly fraught society, and considering the work of the pioneering Black feminists who did so much to put Black women’s rights on the agenda, it is unsurprising that some of the leading voices of the Intersectional feminist movement come from a new generation of Black voices.

If you have just found this newsletter and love discussions on all things literature, as well as connections to both contemporary culture and the art of writing, please consider a free or paid subscription. Paid subscriptions help me to continue to write and research quality newsletters every week - and the yearly fee works out at less than £2 per month! Thank you for reading 😀

Another quality piece that really shines a light on all areas of feminism. Brilliantly written and insightful.

Another great piece! I continue to learn from you.