Woolf, Styles, and the Case for Androgyny

How Virginia Woolf can help us move away from gendered narratives

Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

As the one year anniversary of this newsletter approaches, and I have seen a real upsurge in subscriptions in recent weeks (thank you and welcome if that’s you!) I thought it might be good to share a few of my earliest posts for those who have joined us recently. This one feels as timely as it did a year ago, with the media and politics still full of stories around gender. I hope you enjoy reading!

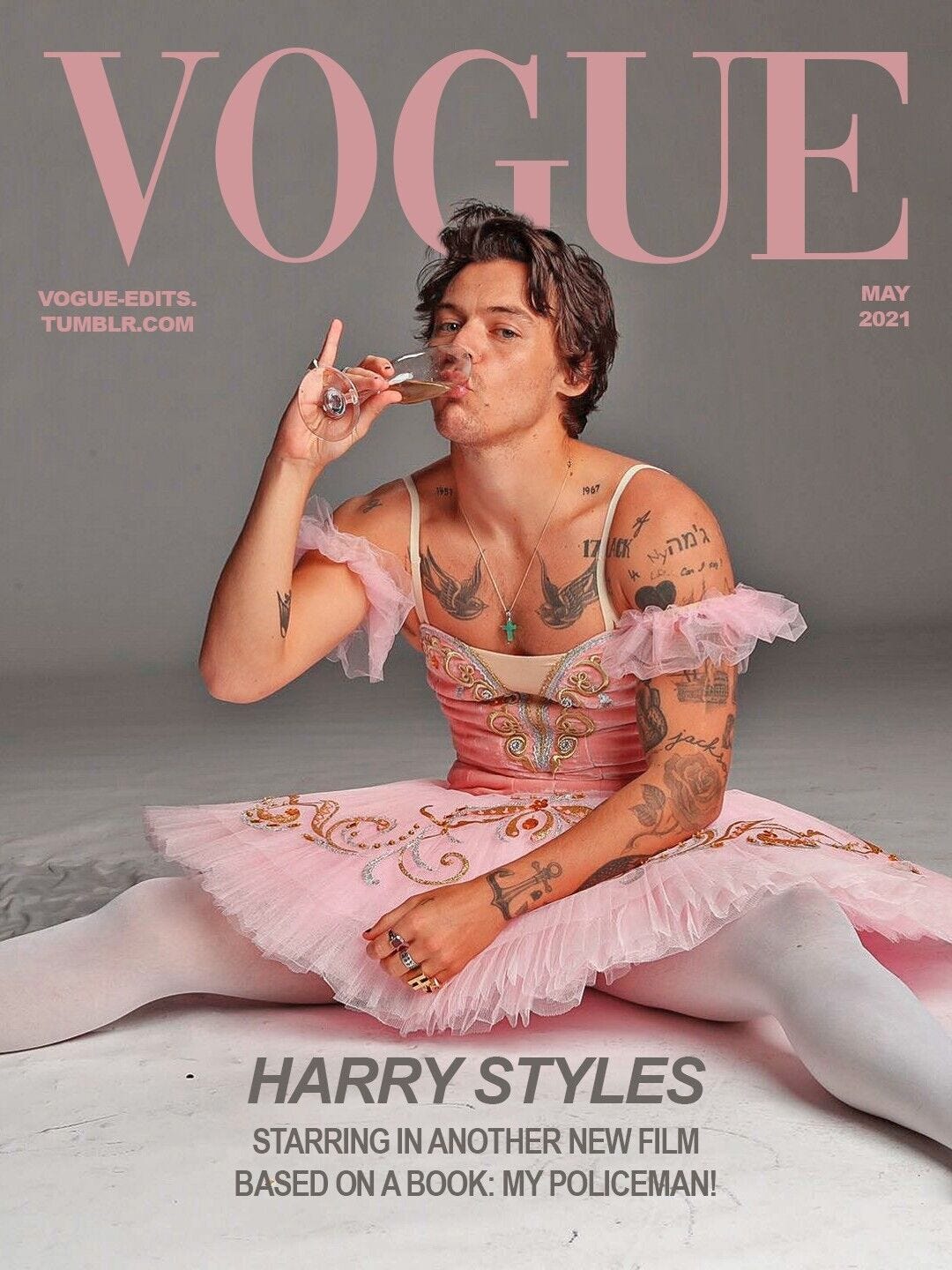

When Harry Styles appeared on the cover of Vogue in 2020 as the first cis male to grace the cover solo, he sparked recriminations from right-wing commentators on social media. Two of the most conservative voices, Ben Shapiro and Candace Owens, were later slammed for their shaming of Styles, with Owens claiming that ‘There is no society that can survive without strong men’ going on to call for a need to ‘Bring back the manly men’ whilst Ben Shapiro, in support of Owens’ views, argued that the cover shoot represented a ‘referendum on masculinity’.

It seems that for both these commentators, the narrative of ‘masculinity’ (and therefore ‘femininity’) is a set gendered binary which may be so fragile that it risks being brought down by the troublesome idea of men wearing stereotypically feminine clothing.

Within literary narratives, nobody spoke more eloquently about the problems with gendered narratives than Virginia Woolf. As a member of the Bloomsbury Group, Woolf was surrounded by a group of writers, artists and intellectuals who sought the freedom to live their lives as they chose. This included liberal ideas around sex and sexuality, with Woolf claiming that ‘No age can ever have been as stridently sex-conscious as our own.’

Although married to Leonard Woolf, another member of the Group with whom she shared a loving marriage with little intimacy, Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando was described as a love letter to her married friend and lover, the writer Vita Sackville-West. Sackville-West often dressed in masculine attire and she and her husband were both openly bisexual, and whilst Woolf’s book has both lesbian and bisexual undertones, at its crux is the exploration of sexual identity and gender.

The book’s full title of Orlando: A Biography, and which Jeanette Winterson referred to as ‘a trans triumph’, hints at Woolf’s satirical take on the traditional Victorian biography. The novel represents the tumultuous history of Sackville-West’s aristocratic family and follows the protagonist, Orlando, as he moves through the centuries meeting famous people from history, his gender changing from male to female as he does so. Woolf skirts the ideas of lesbianism and bisexuality within the novel, at a time when writer Radclyffe Hall was facing a trial for obscenity following the portrayal of openly lesbian love in The Well of Loneliness, her autobiographical novel.

This wasn’t the first time Woolf had discussed the idea of gendered narratives within her work. In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf proposes her ideas for androgyny as a writer, claiming that to be successful as an author, one must embrace an androgynous style of writing. Her suggestion was that women and men needed to transcend binaries of writing in a masculine or feminine voice, creating instead a wholly androgynous voice in which to express themselves within their work. She questioned whether the mind in fact contained two sexes, suggesting that perhaps within the male mind the masculine predominates and within the female, the opposite. In order for the creative mind to operate, she believed, the male-female within the brain must co-operate, allowing for a synergy of creativity to proliferate.

Woolf uses other writers to put credence to her claims, suggesting that Shakespeare and Jane Austen’s writing (which she considers genius) contained such synergy, whilst Charlotte Brontë’s did not, meaning she could not fully inhabit her genius. She further proposed that Charlotte’s less fortunate sister, Emily, would likely have crossed such an androgynous threshold should she have survived to write more than just the one novel, Wuthering Heights.

Woolf was not the first writer to delve into these fascinating ideas of the male-female brain. Samuel Taylor Coleridge back in 1832 had declared that the mind must be androgynous, something to which Woolf refers in her essay, building on this idea and suggesting that the mind which is entirely female – or entirely male – is unable to create effectively. Woolf interprets Coleridge’s ideas on androgyny to relate to the way a mind containing both the feminine and the masculine can utilise the full experience of emotion and to be ‘resonant and porous’.

For Woolf, androgyny allowed both men and women to write without consciousness of their gender, resulting in uninhibited creativity. Woolf also indicated that a truth of a fully developed mind suggests that it no longer needs to think separately of sex or gender.

How wonderful this sentiment is. Let us pause on it a moment: a fully developed mind suggests that it no longer needs to think separately of sex or gender.

Is this not what the publishers of Vogue and their cover story with Styles in traditionally feminine clothing is hinting at all along? That the first man to grace the covers of a usually female oriented fashion magazine gets to wear feminised clothing whilst identifying as a white cis man, and that letting go of such gender stereotyping should be regarded as society’s move towards a loosening of the ideals of masculinity and femininity. A loosening of such ideals need not take away from a cis woman wishing to assert her femininity, or the right of a cis man to engage in ‘manly’ pursuits. It simply allows for an expression of art and fashion and challenges such automatic gendered stereotyping through what we choose to wear on our bodies.

As Styles himself put it, ‘Any time you’re putting barriers up in your own life, you’re just limiting yourself’.

Many celebrities took to social media to shame Owens and Shapiro for their outdated viewpoints on the Styles/Vogue cover, but it was perhaps writer and performance artist Alok Vaid-Menon who raised a vital point that Styles’ white cis male privilege allowed him to receive praise for his stand on the non-gendering of clothing, whereas trans femmes of colour did not receive the same accolades for doing this every day. He was clear, however, that he did not hold Styles accountable for this fact, putting it instead down to ‘the fault of systems of transmisogyny and racism’.

It would be interesting to ascertain what Owens and others considered a ‘manly man’. Presumably not one wearing a dress, in this case. But the proliferation of toxic masculinity within our society points toward a bigger problem than a pop-star on the cover of a fashion magazine. Surely Woolf’s suggestion of the androgynous brain is apt in its application to the way we live now in such a blended society, with the idea that two defined gender identity tick boxes begins to feel more and more obsolete. Further, when we begin to suggest a return to ‘the manly man’, are we not harking back to the stereotyped male/female roles of work and domesticity that so many of us have moved away from?

When I was a child growing up in the 1980’s, the labour within my childhood home was typically gendered, with my mother as the primary caregiver to the children, responsible for the domestic duties, whilst my father brought home a weekly wage and went to football games on the weekend. Within my own 21st century family household, however, the lines are perpetually blurred.

Perhaps Woolf’s ideas sounded radical when she delivered them as part of her lectures at Newnham and Girton Colleges, Cambridge in 1928. Perhaps Coleridge’s suggestions even more so in the 19th century. But are we really willing to overlook in the 21st century the internalised misogyny present in the idea that a man wearing a dress threatens the masculinity of all men? Surely we need to acknowledge that forcing some outdated idea of ‘manliness’ is detrimental on so many levels.

Perhaps it is time to adopt more of Woolf’s ideas of the non-binary brain, free to represent the emotional, practical, wonderful sense of being human, whatever you identify as - in writing as in life.

It was great to re-read this. You always find gems in your pieces.

Fascinating, I love this theme and there is so much context here that I was unaware of. Austen definitely transcends gender boundaries in her writing, and it’s fascinating to unpack why and how.