Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

*Sensitivity warning: this piece contains references to miscarriage and adoption that some people may find triggering. If that’s you, maybe skip this post and read one of my others 🙂

As regular readers will no doubt know, I have an interest in ideas around motherhood and creativity. The ways writers and artists have weaved their work around their children - or conversely, their children around their work - continues to obsess a lot of my own writing and research.

This week, I want to look at a verse play written in 1962 by Sylvia Plath, a writer whose work often comes second to her tragic early death by suicide at the age of 30.

Set in a maternity ward, Three Women consists of three interwoven monologues and surrounds the whole concept of motherhood.

The first of the three women within the play gives birth and takes the baby home in what would be recognised as the usual outcome of labour, although no father is mentioned. The second features a married secretary who has suffered a miscarriage, and the third an unmarried student who gives her baby up for adoption.

To read the play in full, see this link or for a recorded version see this link. The play was also first broadcast on the BBC in August 1962 and performed by Barbara Jefford, Jill Balcon and Rosalind Shanks. Despite this, it is an often unknown piece of work by Plath, and I only came across it a couple of years ago in the back of a poetry collection.

The subject of motherhood would have been at the forefront of Plath’s mind when she wrote the play as it came just a few months after the birth of her second child, Nicholas. The play movingly captures the experiences of the three women’s voices in a way that you would expect from her visceral poetry around motherhood. The language used by the first woman’s voice is particularly resonant of many of the poems in her Ariel collection, such as labour as "A seed about to break," and the complex feelings of giving birth to an unknown entity "Who is he, this blue, furious boy . . . ?" as well as expressing her feelings of becoming "a river of milk, . . . a warm hill".

‘What did my fingers do before they held him?

What did my heart do, with its love?’

The second woman’s sadness is tempered with a sense of guilt at her miscarriage, referencing that "It is a world of snow now" and indicating that this is not her first ‘failure’ to produce a child, heartbreakingly believing that she is only able to "create corpses." When she leaves the maternity ward, she returns to her job and husband with a terrible sense of isolation, referencing herself as "a heroine of the peripheral." Some critics have indicated that as Plath also lost a child to miscarriage during the early parts of her marriage, that this voice perhaps most reflects her own experience and sense of loss and isolation.

As you would expect, the third voice in the play reflects the helplessness of unwanted pregnancy, as the woman responds to the life inside her as "the face . . . shaping itself with love, as if I was ready." Once the baby is delivered however, she refers to her as "my red, terrible girl," seeing her child only through the glass before she returns to her college life, feeling like "a wound walking out of hospital."

As a whole verse play, the three women’s voices say a lot about the experience of labour and motherhood. Not getting involved with the clinical aspects of labour, Plath uses her instinctive feel for imagistic language to provide insight into the minds of the three new mothers, and the play sits within the poetic personas she develops in her collection Ariel. The fact that Plath chose not to name any of the three voices in the play speaks volumes to her intent to portray this ordinary yet extraordinary everyday occurrence, and the often complex intricacies for women around fertility and reproduction. Plath reportedly saw the idea of ‘God’ as a symbol of patriarchy, and therefore the suffering by women during labour and childbirth as a conspiracy because they were the only sex to be able to give birth.

In her second voice, Plath expresses some of this aggression towards male dominion, later expressed in Plath’s poem ‘Lady Lazarus’ in which the narrator wishes to ‘eat men up like air’.

‘It is these men I mind:

They are so jealous of anything that is not flat!’

Similarly, she saw the connection between the ability to give birth and writing as both creative processes which were inextricably linked. This can be seen in Ariel, arguably her most prolific and accomplished poetry collection, completed after the birth of her two children.

Critics have pointed to the fact that within Plath’s marriage to fellow poet Ted Hughes, many other writers and visitors to their home were unaware that Plath also wrote poetry. She often acted as editor and secretary for his work, and made many compromises in their early marriage, deferring to his own work. Within her later poems in Ariel, however, we see a more confident and empowered version of womanhood, later identified as a unique version of female power.

Some critics have sought to exclude the third voice from their discussions as she is perhaps not conceived as a ‘mother’ in the traditional sense. She gives up her child, seen by some as abandonment, but this denies the complex experience of this voice in the play. Early references to her as ‘the girl’, for example, points to Plath’s possible intention to draw attention to the youthfulness of the woman. The play’s language also conveys to the attentive reader the sadness of this voice; she does not walk away from her daughter easily.

‘I am a wound walking out of hospital….

I leave my health behind. I leave someone

Who would adhere to me.’

Returning to her college life, meanwhile, she wonders “What is it I miss?” and expresses bitterness against both society and the male doctors in the ward. Further, the first and third voices are juxtaposed as the new mother of the first responds to her son’s birth “I am ready”, whilst the third responds bitterly “I wasn’t ready”, both in reaction to the violent act which ended in her pregnancy and the delivery of her daughter.

Plath’s play illuminates the complex ideas surrounding motherhood and childbirth, as well as the ambiguity of experience of the mother/child relationship, and the dominance of the institution of the maternity ward.

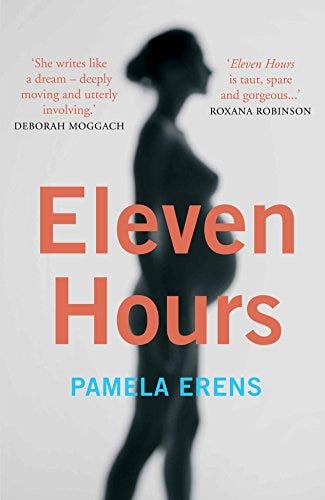

Interestingly, Plath’s play reminded me of a short contemporary novel I read a couple of years ago, Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens. Within it, a woman attends a maternity unit in labour, and is attended by her midwife, herself desperate to have a child with her husband and having suffered several miscarriages.

The book weaves these two disparate women’s narratives during the eleven hour labour of Lore, who has attended the hospital alone. It is revealed through her narration that her partner chose to be with another woman, leaving her alone and isolated in childbirth. She is not weak in this position, however, and is fiercely independent in her ideas around both birth and single motherhood. She is making the choices and is in control, as far as anyone in labour can be.

Franckline, meanwhile, tries to break through Lore’s hard exterior to the vulnerability inside, whilst relaying her own story of leaving Haiti after a terrible trauma and making a life in the US with her husband. She feels a failure at her inability to produce a healthy, living child, despite their happy marriage and her husband’s support. Both women have to face down their past traumas in order to move into the next phase of their lives.

Whilst this story reflects a more modern concept of motherhood and miscarriage, I saw similarities in the juxtaposition of the two women’s stories in Eleven Hours to Plath’s three women of her play.

Both the women in Erens’ novel - as with Plath’s three narrators - feel they are weighed down by the expectations of their sex, and therefore experience the pain and discomfort of their ideas around mothering and fertility. I think this shows that the relevance of Plath’s ideas are still prevalent within a society that both idealises, yet often disregards, the exceptional and differing experiences of women and mothering.

Wonderful piece. So sad she passed away so early, such a loss.

Thank you, Kate. I always like learning more about Plath and her work - she is laid to rest not too far from where I live. And I’m such a fan of your writing - beautiful :)