Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature, as well as reviews of great books and recommended reading, please consider a free or paid subscription.

*This essay contains themes that some may find triggering.*

The marriage of literary modernist Virginia Stephen and Leonard Woolf has been a relationship that has held a deep fascination for me for some time.

Ever since I discovered the love letters between Virginia and Vita Sackville-West, I have pondered the former’s marriage, which always appeared to have been a supportive and loving union, not to mention the affectionate portrayal of the couple through Michael Cunningham’s The Hours.

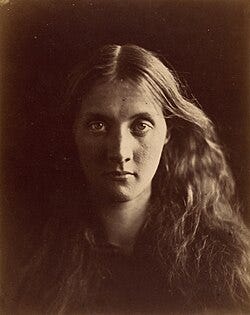

Virginia Stephen was a somewhat fragile young woman: her mother Julia died at the age of 49, when Virginia was just thirteen, sparking a lifelong battle with depression. By the age of twenty-two, Virginia had also lost her father and half-sister, Stella Duckworth, leading to Virginia’s first nervous breakdown. Stella was Julia’s daughter to her beloved first husband, whom she lost at the age of just 24, leaving her with three young children.

Virginia also reported being sexually abused by her half-brother George Duckworth over many years, up until the age of twenty two. It has been suggested that this abuse contributed to a lifelong issue of a fear of sexual relations within her marriage, as well as her first severe mental breakdown in 1904.

In her youth, Virginia was described as having a fragile, delicate beauty, which was a part of her charm. She was however, not unusually so for the era, naïve and emotionally immature, understandably afraid of men, and reportedly worried about the thought of the sexual demands of marriage.

By her late twenties, Virginia faced the same pressure as other young women of her age and class to settle down and get married.

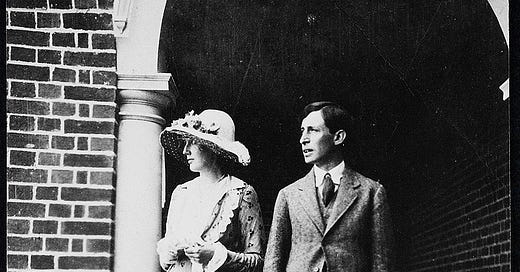

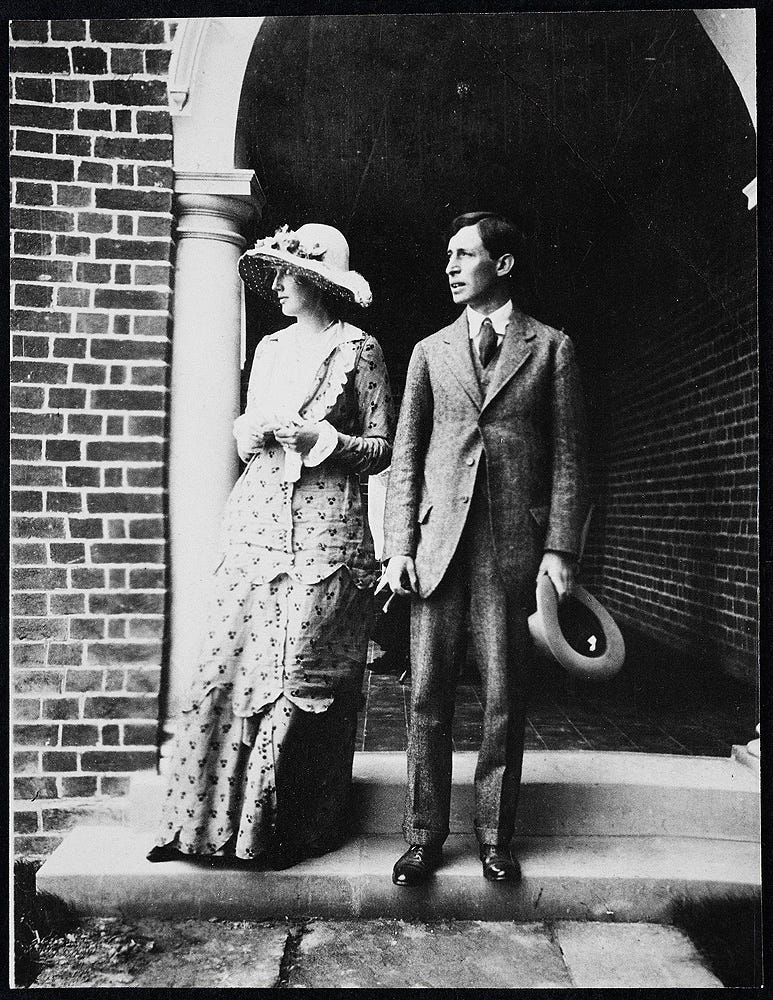

Whilst visiting her brother Thoby at Trinity College, Virginia first met Leonard Woolf, who commented that Virginia’s white dress and parasol made her resemble a Victorian young lady. Virginia had many prospective suitors, including another of the Bloomsbury Group, Lytton Strachey. In February 1909, Strachey even went so far as to propose to Virginia, despite being homosexual, withdrawing his proposal the next day, which Virginia accepted gracefully.

It was two years later when Virginia and Leonard next met, after he returned to England from Ceylon. Needing a place to stay, Leonard rented rooms on the top floor of Virginia and her brother Adrian’s house in Brunswick Square, London, and the couple began dating soon after.

Their courtship lasted for six months, with Leonard proposing several times. Virginia however remained fearful of marriage, responding to a proposal of Leonard’s somewhat bluntly:

“As I told you brutally the other day, I feel no physical attraction in you. There are moments—when you kissed me the other day was one—when I feel no more than a rock. And yet your caring for me as you do almost overwhelms me. It is so real, and so strange.”

Despite this, Leonard proposed again, whereupon Virginia finally accepted and the couple became engaged. Writing to her friend Violet Dickinson, she confessed:

“My Violet, I’ve got a confession to make. I’m going to marry Leonard Woolf. He’s a penniless Jew. I’m more happy than anyone ever said was possible – but I insist upon your liking him too.”

Virginia and Leonard were married on 10th August 1912 at St. Pancras Registry Office, following which they spent their wedding night at Asheham House in East Sussex, before honeymooning in France, Spain and Italy.

Despite Leonard’s discovery of Virginia’s reluctance to consummate the marriage, it appears that he was understanding around this, and the couple nonetheless considered having children together. However, due to Virginia’s previous history of mental instability, shortly after their marriage, doctors advised her to refrain from becoming a mother. She was heartbroken, having witnessed the joy children had brought to her sister Vanessa and being a devoted aunt to them.

In 1922, Virginia met the aristocratic writer and acclaimed gardener, Vita Sackville-West at a dinner party, where Vita was captivated by Virginia’s charm and wit. Throughout the next decade, the women exchanged many letters expressing their love and erotic fascination with one another, with the full awareness of both husbands. It seems that Leonard realised Vita had an enormous positive impact on his wife, including inspiring one of her most enduring novels, Orlando, published in 1928, and referred to by Vita’s own son as: “the longest and most charming love letter in literature.” It is also considered to be one of the earliest novels with a gender fluid protagonist.

Virginia and Vita shared their work with one another, helping to critique the writing that would later go on to be published.

"Dear Mrs Woolf, (That appears to be the suitable formula.) I regret that you have been in bed, though not with me – (a less suitable formula.)" (Vita to Virginia)

Evidence from Virginia’s diaries strongly suggests a profound and genuine affection towards her husband, and much has been debated around their relationship being one of mutual love and devotion without consummation. It would appear that Vita was Virginia’s first affair and for both women, their relationship was a formative experience, both physically and through their ongoing exchange of correspondence over many years. Their letters show a flirtatious, joyous, passionate love between the two women, however, it also appears true that both women were happily married to their husbands.

"Darling, there is no muddle anywhere! I have gone to bed with her (twice), but that’s all." (Vita to her husband, Harold)

Writing in her diary, Virginia referenced her love of Vita’s body: ‘as a body hers is perfection,’ whilst also referencing Vita’s capacity to control a household and her aptitude for motherhood- though appearing a little cold to her boys- she somewhat sadly references Vita as: ‘being in short (what I have never been) a real woman.’

Though Virginia appeared the more fragile, devoted of the pair, with Vita enjoying other love affairs with both men and women outside of her marriage, their passion eventually subsided to a more enduring friendship. Their last recorded meeting was on February 17th, 1941, and their last letters are dated March of that same year.

During the Woolf’s marriage, it seems that Leonard often put his wife first, recognising her creative genius and encouraging her to work on her writing. He neglected his own work as a journalist and editor, dedicating himself to the care of Virginia, meticulously organising her timetable and nursing her through her various mental instabilities.

Virginia had manic episodes which often began with terrible headaches and an inability to focus, before descending into hyper-excitement and delusions where she frequently heard voices speaking to her. This was followed by a depressive phase where she would find herself in the depths of despair, whereupon she would refuse to eat.

Despite such terrible ordeals, Virginia successfully worked on her writing for many years, with each book she wrote leaving her close to nervous exhaustion. Her dedication to her writing and the accomplishment of her wholly original, modernist novels indicate that her husband’s care must have been imperative to her at this time.

The couple later set up a printing press together, Hogarth Press, which they utilised to publish both Virginia’s works and other writers within their milieu. Part of the infamous ‘Bloomsbury Group’, Virginia and her sister, the artist Vanessa Bell, and writers and artists such as EM Forster, Lytton Strachey and Roger Fry, were influential in developing the modernist movement in art and literature. A turning away from the large realist tomes of the earlier century, their works developed new forms and structures, written with an eye to aestheticism rather than realism.

Virginia’s final letter written to her husband before taking her own life shows the depth of her affection.

‘Dearest – I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will, I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you.’

Following his wife’s death, Leonard published five volumes of his wife’s uncollected essays, as well as editing a selection of her diaries. He continued to live between Monk’s House and London, overseeing Virginia’s legacy, as well as working on his own writing and interest in politics. He published a third volume of his series After The Deluge in 1953, and a five-volume autobiography, A Calendar of Consolation in 1967. He never remarried, though did reportedly have a relationship with a woman named Trekkie Parsons.

After his death in 1969, Leonard was cremated and buried beside Virginia in their backyard at Monk’s house, beneath two elm.

If you’re new around here, I usually write about all things women literature related. Please consider a free or paid subscription - your support helps keep this newsletter afloat!

This a great post not only about Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf but about the possibility of happiness and the possibility of a deeply caring relationship (marriage or nonmarriage) and about the fulfillment that writing offers regardless on whether one is alone or with another kindred caring soul present in the immediate environment. One can always feel the possibility of being closer or nearer to the Cape of Good Hope than to Cape Fear whether regarding writing or relationships.

This was fascinating, thank you. What a poignant final letter to Leonard.