Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you value the work that goes into writing this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber today. Your support makes this work possible.

I read a while ago a phenomenal short story collection to rival that of the king of short stories, Raymond Carver.

But the writer, unlike Carver, was someone I hadn’t come across before. It had been a mere fluke that I picked up the collection at my local library, and so as I often do, I set out on a voyage of discovery into the life and work of this enigmatic writer.

Lucia Berlin wrote short stories - often more like ‘sketches’ - of people living lives very similar to her own. Her work is sometimes referred to as ‘auto-fiction’. The form of ‘auto-fiction’ (also called ‘self-fiction’) references work narrated as though straight from a writer’s own life, almost unchanged, but selected and told artfully, so as to create its own kind of fiction.

“ [to] form a body of work that is part memoir, part auto-fiction, and part single, extended story cycle”. The Guardian

Berlin was a master of this technique. She changed what she needed to in order to add colour to her stories, or to fit the chronology, but as short story writer Lydia Davis points out in her introduction to the collection, even one of her sons was no longer sure of what really happened in some of their family memories, so moulded and rewritten had they been. His mother, he says, assured him that this did not matter, claiming: “The story is the thing.”

Davis was an early adopter of Berlin’s work, acquiring her 1981 book Angels Laundromat and becoming an avid fan. Davis points out that Berlin’s rich and diverse life experiences from childhood and beyond heavily influenced her stories. From the mining camps of the west to her mother’s family in El Paso, she eventually found herself in a life of privilege in Chile. She portrays this chapter of her life through a teenage female character in Santiago, relating tales from Catholic school and politics, to yacht clubs and slums.

Her adult life was no less restless, living variously in Mexico, Arizona, New Mexico, and New York City. Her son recalls moving around every nine months as a child, with his mother ending up teaching in Boulder, Colorado in later life. Later still, she moved again, to Los Angeles this time to be closer to her sons.

Her sons’ lives are often featured in her work, relating the various jobs she took to support them, through imaginary other women’s stories. Davis claims that her writing is so enjoyable because we can relate some of it to our own lives. We have all experienced something of what she has been through; be that a rapturous love affair or struggles with addiction. Her life experiences were so wide ranging that they became universal; at least one person reading her stories will have experienced the same or similar as her narrators.

Her stories contain perfectly paced narration and she tells the story in just the right amount of words. They also contain a lot of humour, even in the darkest of times. Just as in life, Berlin used humour to defuse a difficult situation. In the story of a dying sister, for example, she proclaims:

“I’ll never see donkeys again!”

This ends up with both sisters breaking into laughter, but the poignancy of the story lingers: death is close by, there will be no more of so many things.

She was the queen of the underplay. Her endings, when they come, are often surprising yet inevitable. She uses the difficult experiences of her own life and fictionalises them until they become bearable. She claimed to believe in being truthful in her writing, “the story had to be real”, regardless of the way she dealt with it in her fiction. This is one of the reasons I think the writing is so striking; that nugget of truth shines through in each story.

“The story itself becomes the truth, not just for the writer but for the reader. In any good piece of writing it is not an identification with a situation, but this recognition of truth that is thrilling.” The New Yorker

One of Berlin’s sons claimed, following her death, that his mother wrote “true stories, not necessarily autobiographical, but close enough for horseshoes”. The New Yorker

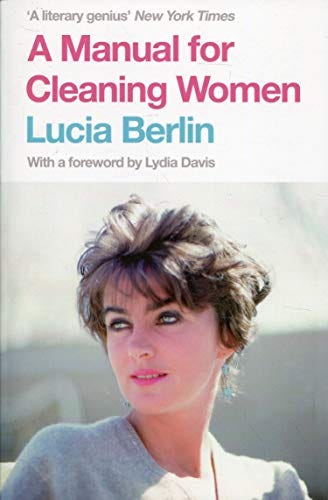

Lucia Berlin died in 2004, however it wasn’t until 2015 that A Manual for Cleaning Women was released, containing just over half of her total of 76 stories, penned between the years 1960 and the early 2000’s.

I wasn’t surprised to discover that I wasn’t the only one to have found a new voice: for many readers, the substantial work of Berlin was something which appeared out of nowhere. Even though much of her work had been published in the 1980s and 90s, she appears to have gone fairly unnoticed, despite one of her books winning the American Book Award.

Her work in A Manual for Cleaning Women contains the typically humorous-tinged-with-sadness conversational type of stories you might expect from writer Charles Bukowski, with its cast of addicts living somewhat chaotic lives.

“It’s not that I’m worried about the future that much…It’s my past that I can’t get rid of, that hits me like a big wave when I least expect it.” ‘A New Life’

Berlin was married three times, birthing four sons, and becoming an alcoholic like her mother before her, as well as several other family members.

Her list of employment roles is considerable, and includes a high-school teacher, emergency room nurse, and cleaning woman. Her work roles are often present in her stories, as are scenes in the laundromat.

“I like working in Emergency, you meet men there, anyway.” ‘My Jockey’

When asked about her similarities to the work of short story writer Raymond Carver, Berlin says she wrote like him before she ever read his work, saying he also liked her work, both writers recognising their similarities immediately.

I was drawn to her work because of my on-going interest in the writing of Grace Paley, another writer to which connections were made. Both Berlin and Paley write of the characters who populated their lives, living in their domestic milieu. They wrote of work and mothering, and of merely getting by. Often lives of ‘quiet desperation’ to quote Thoreau.

She has also been connected to the work of Anton Chekhov and Proust, even acknowledging these writers in a couple of her stories.

“Maybe I’m morbid. I am fascinated by two fingers in a baggie, a glittering switchblade all the way out of a lean pimp’s back. I like the fact that, in Emergency, everything is reparable, or not.” ‘Emergency Room Notebook, 1977’

What makes her stories so rich are the ways in which she reacts to the characters in a wholly humane way. She does not distinguish good from bad; these are real, flawed people, in all their humanity. Her writing style is of a realist nature and even when a character appears beyond redemption, she will give them something; a witty characteristic, or a charming and thoughtful demeanour towards others.

She was also, apparently, not keen on the word ‘love’, moving away from any type of sentimentality in her work. She was quoted as saying that she had loved Carver’s work:

“Before he sobered up and sweetened his endings.”

She does however allow for the bittersweet in some of her stories, allowing for the juxtaposition of horror and hope, lightness and shade, and more shade. She tackles big issues such as suicide, alcoholism, and sexual abuse, and yet her stories emerge as refreshing, rather than depressing.

“I don’t mean the hard things, like love, but the awkward ones, like how funerals are fun sometimes or how it’s exciting to watch buildings burning.” ‘Dust to Dust’

Characters often reappear in the stories, making it relate even more to memoir rather than fiction. These characters feel all too real. When she returns to their stories, she often relates their lives from a different angle, allowing us to see, as in real life, the ways in which stories are not always what they seem. Like the ultimate unreliable narrator.

In Berlin’s final story, ‘BF and Me’, her character is an old woman living in a trailer park, attached to an oxygen tank, attempting to procure the services of a tiler to work on her bathroom. This story in particular has been suggested as resonant of the work of Proust.

Born in Juneau, Alaska, in 1936, Berlin died in 2004 at the age of 68. As with many women’s narratives, her work has left a legacy behind that she likely couldn’t have imagined.

If you have just found this newsletter and love discussions on all things literature, as well as connections to both contemporary culture and the art of writing, please consider a free or paid subscription. Paid subscriptions help me to continue to write and research quality newsletters every week - and the yearly fee works out at less than £2 per month! Thank you for reading 😀

Kate, your articles are always refreshing and enlightening. Thank you for introducing me to a new author and making me excited to explore their work.

Some of the best short stories I've ever read, love Berlin.