The Letters of Sylvia Plath

How Plath's letters reflect the everyday domesticity of the mother/writer

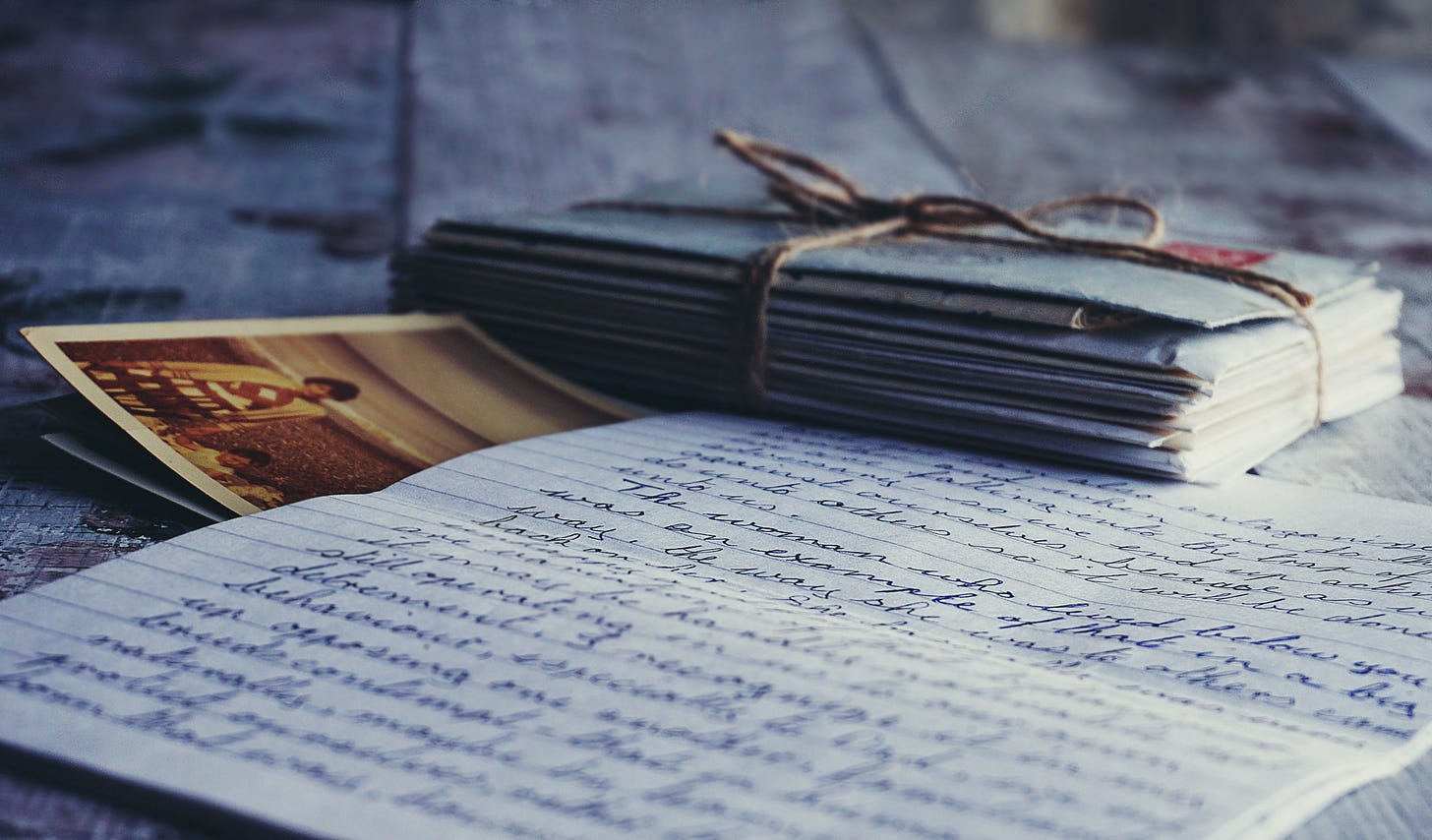

Image by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels

As it was the 60th anniversary of the death of Sylvia Plath, writer and poet, on 11th February, I thought I would re-post my earlier newsletter on a consideration of her published letters, particularly as a substantial amount of new subscribers have joined us since it was first published.

I hope you enjoy this if you missed it the first time around. If you aren’t a subscriber, I would love you to join our literary community - whether as a free or paying subscriber - for more literature discussions!

Does anybody bother to write hand-written letters anymore?

This was a question I found myself asking last weekend after I picked up a gem of a book from the local library, Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Written in History: Letters that changed the world. Montefiore’s book contains letters between everyone from Frida Kahlo to her husband Diego Rivera; Henry VIII to his future wife Anne Boleyn; and even Donald Trump to Kim Jong Un.

Considering the plethora of writers famous for their letters, which have often been put into collections as precious and in demand as their novels and poetry, I wondered if letters were a good way to practice the art of writing. Reading Kahlo’s short but revealing letter to her husband Diego, it occurred to me that they can be works of art in and of themselves, even when they relate the everyday occurrences of life.

On a personal level, I still have short, hand-written notes from my mother which contain the most mundane of missives, yet they are amongst some of my most precious keepsakes.

A good letter, particularly when written by a great writer, can reveal so much more than that which is discussed. Many can contain seemingly inconsequential nuggets of information on everyday occurrences, yet tell a larger story about not only the writer and recipient, but also the society of the day. In my mother’s notes of how long to leave the pot of stew in the oven, or where she has placed the clean laundry, I find examples of her devotion to her family and the loving care with which she attended to our needs.

Post-modernist poet and novelist Sylvia Plath wrote letters her whole life, from her adolescence living with her mother and brother in Wellesley, Massachusetts, to a week before her death in 1963. Many of these have been captured in various volumes of letters, including one published by Plath’s mother Aurelia Letters Home, (1975). Many of Plath’s letters are to her mother back home, but she also consistently wrote to her friend and former psychiatrist, Ruth Beuscher. Many of these later letters reflecting her life in the last few months before her suicide in 1963 were controversially sold in 2017, later being obtained by Smith College, Plath’s alma mater, who filed a law suit after some were posted online.

Plath’s daughter, Frieda, eventually reviewed these later letters for publication. This raises the issue of consent. Unless a writer has specifically made their wishes to have their personal letters published after their death, do their surviving family members have the right to publish these? Once a letter has been received, does this then become the property of the recipient, free to publish at will, regardless of how private or revealing the contents?

Whilst Plath’s many letters home revealed the poetic genius of her flair for composition, such as her whimsical descriptions of the “sweet gentle mousish face” of the groundhog, much of the letters to Beuscher contained in this final volume were written in a more formal, plain prose, perhaps reflecting the honest doctor/patient relationship they shared. It seems that Plath was often ‘performing’, or perhaps practising her skills as a poet when writing her letters to her mother and others, whilst her letters to Beuscher reveal the depth of the two women’s relationship.

What was controversial was the revealing nature of her letters to Beuscher regarding the treatment towards her of her husband, the poet Ted Hughes, claiming he “beat me up physically”, shortly before a miscarriage, and claiming her husband appeared to want her dead.

In the foreword to the new edition, however, Plath’s daughter Frieda defended some of the statements made by Plath against her father, insisting that such allegations had not been made in previous letters, and suggesting that as the couple’s relationship was over, Plath would likely wish to portray him in a less than favourable light. She further points to the importance of “context” of the incident referred to in Plath’s letter, claiming that her mother had ripped up papers belonging to her father, and that as writers, her mother had hit out at the one thing which was held most precious: his manuscripts. This raises questions over the reliability of words in private correspondence, and again the topic of consent. We have to question whether Plath’s personal revelations in letters to her psychiatrist/friend have any more right to be released into the public domain as Plath’s psychiatric records would be.

What I find more interesting are how many of Plath’s published letters contain more mundane topics around her family and domestic life, as well as her writing life, showing the way she combined her writing ambitions with the everyday. In one of the most endearing accounts, she speaks of purchasing material to make clothes for the baby Frieda. She planned to make enough money from the publishing of her poetry to purchase a sewing machine on which to make the clothes for her child, something which brings her pride and a sense of accomplishment. In a poetic version of circularity, Plath then uses this within her poem ‘An Appearance’.

I found this idea compelling. In this example of the practicalities of a new mother in the early 1960s, longing to sustain a creative career as a working poet whilst combining the complexities and demands of new motherhood, we can sense the age-old claim of a woman’s need to create around her domestic demands. From this standpoint, we can see how Plath stood by her husband in his blossoming career as a poet, celebrating his accomplishments as the awards and publications began to roll in, whilst harbouring her own need to be recognised as a professional writer.

Plath herself, meanwhile, continued to plug away at the poetry that would eventually make her famous, whilst also attending to the everyday necessities of a wife and mother. These kinds of issues were something touched on in her only published novel, The Bell Jar, (1963), in which the young narrator Esther Greenwood struggles to think of a future in which she would wish to become a mother, and her negativity towards such a role. In Esther, Plath’s own mental breakdown and concerns are revealed, yet it is interesting to note that much has been recorded of Plath’s success at being a loving and dedicated mother and wife to Hughes.

This discrepancy is something which I have always found fascinating about Plath, as her earlier journals and concerns within her writing seem to indicate that she could not conceive of combining her writing ambitions with the traditional demands of marriage and motherhood. Adding to this complexity, is her collection of poems Ariel, which she was furiously working on for the last few months of her life. Rising early whilst her children slept and following her split from Hughes, who had left her for Assia Wevill, has often been lauded as her most accomplished work. Within what must have been the darkest and most painful period of Plath’s short life, her genius for words illuminates the page within such poems as ‘Lady Lazarus’ and ‘Daddy’. Her tragic suicide following the writing of these poems robbed the world of further work by this genius writer, and more importantly, the loving mother to her two young children.

But I wonder at the praise often heaped on Plath that she was a good mother despite her reservations, and that she produced her best work following this. If you read and study Plath’s journals and letters, her prose often exhibits an insatiable need to express herself; to be heard and to be taken seriously. But what also comes across distinctly is Plath’s perfectionism. Her need to accomplish.

A traditional high-achiever, Plath attended the prestigious Smith college, as well as later becoming a Fulbright scholar at Newnham College, Cambridge. Within her accomplishments as a mother and homemaker, therefore, it is likely that Plath also felt the need to excel in this as she had in all other areas of her life. As her letters to her mother often show, even in her letter writing she tries hard to deliver the simple facts of every day living in a shimmering prose that defies a simple letter home.

In Plath’s story of the purchased fabric for her daughter’s clothes however, and the wish to sell her writing in order to fund a sewing machine in which to make these clothes, it is easier as a mother/writer to feel closer to this genius perfectionist of a poet. I see the simplicity in her words. In her wish to sell her work in order to fund something practical for her child, I can connect to her need to see herself as a professional writer and working mother. Something which is more ‘acceptable’ in today’s society perhaps, but which nonetheless still poses difficulties in the practicalities of the domesticity of the everyday.

Postscript: If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy my review of Euphoria, the new novel about Plath’s final year.

You bring up a lot of interesting questions here about Plath's work as an artist and identity as a mother/wife. Tough questions! The way you frame the idea of letter writing is also useful...she at once becomes more human and universally relatable but also supremely unique in the way here art came from experience. It's a sad story and here we can see that while Hughes was clearly a terrible part of her life much of the time, Plath was perhaps also her own worst enemy at times. Her poetry, ironically, feels so nurturing and healing even when she talks of difficulties and even trauma. Even my high school students loved her work for this reason...I think the realness of it all is something deep within us that she's not afraid of capturing. Also - I love handwritten letters. Why does it feel so hard to find the time to write them 'these days'? Thanks for a great investigation and reflection, Kate.