Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

In my recent essay on Penelope Mortimer, I briefly touched on the categorisation of ‘The Hampstead Novel’; a term originating in the 1950s by mostly male critics referencing female novelists who wrote novels ‘around the pine kitchen table’. Such novels were said to be ‘by women for women’, chafing under the shortcomings of men and the patriarchal society of the 1950s and 60s.

These female novelists were often labelled by the new-wave Women’s Movement as ‘feminists’, regardless of whether they openly identified with this title or not. Penelope Mortimer would have perhaps fallen into this critical assessment, regardless of the fact that neither her life nor her characters necessarily resembled a typical example of the feminist woman.

The title of the Hampstead novel was formed around the fact that many so-called ‘domestic’ novels of this era were set within the London Borough of Hampstead, North London. Seen as a plush London suburb, the genre was categorised as featuring ‘middle-class orgasms, delicatessen food and high thought’, according to critic John Sutherland.

Regardless of Sutherland and others’ diminishing attitudes towards the genre, it had a good deal of influence on British literature of the time.

Although many examples of the genre were set in the north London suburb, there were also many that were not. It was more often used as a reductionist term for a specific type of novel and novelist. The genre emerged during the more affluent 1950s and generally explored English bourgeois preoccupations, written in a realist, serio-comic style.

Stories often featured characters such as Cambridge graduates falling pregnant by BBC newsreaders, or working-class lecturers climbing the academic ladder. Their ideal readership was the homogenous, white, middle-class, conservative set living in an era before multiculturalism, feminism and the permissive society.

Though the term often came to blur with the domesticated fiction of white middle-class women, some early classics of the genre included books by male writers such as Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim. But books such as Margaret Drabble’s The Millstone and Margaret Forster’s Georgy Girl were popular examples which have gone on to enjoy a somewhat classic status. More recent authors grouped within the genre have been Ian McEwan, Fay Weldon and Zoë Heller.

Many critics have argued that the Hampstead novel dwindled in the 1980s due to British society having changed radically, with the welcome arrival of non-white authors and a more multicultural London milieu. Some however have argued that the postmodern era has boosted the Hampstead novel, manoeuvring itself into a hegemonic position that snobbishly attempts to assimilate itself within all genres, with others claiming that the genre is in fact more aligned with the mainstay of English literary fiction.

In its hey-day, the Hampstead novel was shorthand that became known by all as signifying a middle-class morality novel, usually featuring adultery and often shallow characters who masqueraded as deep and philosophical. Critics had originally chosen the title of ‘Hampstead’ to indicate a setting and type of Britishness that gave an indication of the content of the novel. The postcode itself was seen as a precursor to a certain type of person or people, though it could be argued that Hampstead may never have had much to do with reality. Sutherland argues that the title became more an idea than a ‘topographical truth’; a sneer or poking-fun-at the often high thought contained within its pages.

Margaret Drabble, one of the key proponents of the so-called Hampstead novel, has often attempted to shrug off the name, explaining to critics and readers that the reality of living and writing in Hampstead was not the reality that readers imagined. She claimed that the area was not, in fact, a wealthy suburb as many imagined, instead containing intellectual and progressive inhabitants. Neither was it exclusively middle-class, according to Drabble. She remembers her mother, visiting from her home in Yorkshire, and recoiling from the squalor of the area her daughter had chosen to make her home. Drabble states that her mother expressed “I thought Hampstead was a nice place,” clearly unimpressed by her daughter’s new situation.

But like many literary ideas, Hampstead’s fictional identity persisted, despite Drabble’s protestations. She even went so far as to suggest that the name was an invention of the ‘Thatcherite Press’ in an effort to patronise left-wing writers such as herself. The title persisted for another couple of decades however, with many big named women writers falling within its remit. Authors such as Beryl Bainbridge, Penelope Lively, and Edna O’Brien joined the ranks of the Margarets’ Drabble and Forster. What is interesting however is that on inspection of many of these novelists’ work, they often neither lived in nor wrote about the suburb of Hampstead at all.

What this led me to wonder was whether the name had, in fact, retained much of its allure for (male) critics of the era as a way to dismiss the ‘domestic fiction’ written by many successful female novelists of the time.

As I have written before, and as reported by Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own, writing by men was often seen as ‘Important’: political tracts and historical fiction; war stories and deep, insightful or philosophical probes into the world and the psyche of Man.

Domestic fiction (based in Hampstead or otherwise) came along as an anathema to such works. The analogy of the female novelist ‘writing around the pine kitchen table’, albeit sounding reductionist and with just a hint of the curled lip of the Serious Novelist, actually makes a lot of sense.

Women writers, often writing around domestic chores and the mores of their families, would likely have been writing around the kitchen table (pine or otherwise).

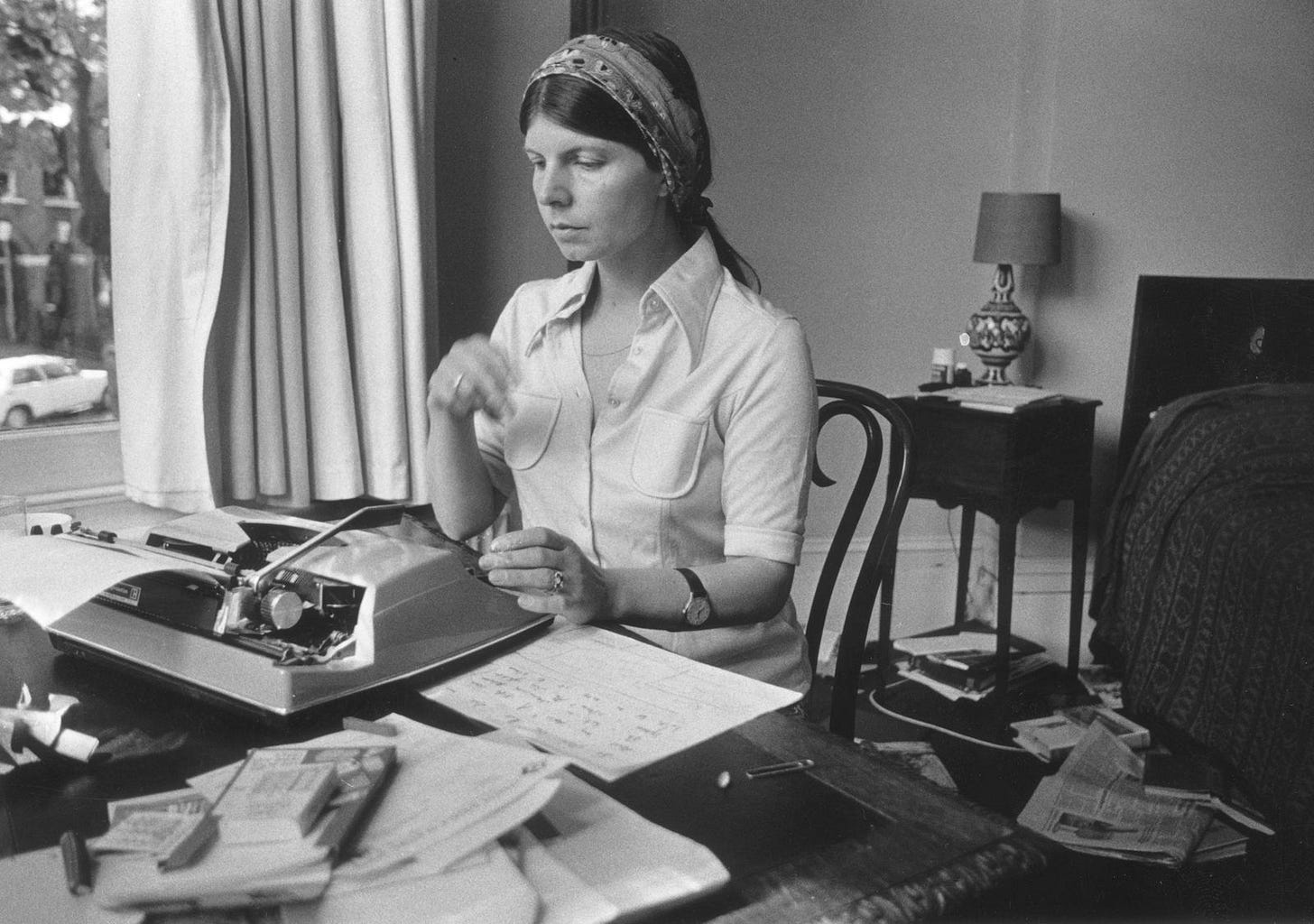

I came across the photograph of Margaret Drabble below many years ago. Drabble is a young mother at the time, seated at her table, tapping away at her typewriter. It is clear from the photograph that she is working amongst the detritus of the family home.

The interesting thing (for me) is that when I encountered this image of Drabble years ago as I discovered her work as a young mother myself, I distinctly remember thinking: How cool is this woman?! In this image of her sitting at her table amidst the family chaos, the look on her face one of complete devotion and focus on the paper in front of her, fingers poised ready for action, I saw what I wanted to emulate. I wanted to be the writer in front of the typewriter; I wanted to work out how to combine the need to write with the need to also care for a young family.

Drabble has over six decades of book writing under her belt at this point, so she wasn’t a bad role model to look to.

Whilst Drabble herself may have found the Hampstead title reductionist, there are certainly hallmarks in a typical Drabble story. Much of her writing focuses on different aspects of women’s lives and the men who populate them. But comforting family sagas they are not: they contain a provocative intelligence and a shrewd eye for character. They span the years that she has been writing; in The Millstone, for example, which she wrote as a young mother herself (probably at her kitchen table in Hampstead, no less!) we see a young woman grappling with the enormity of becoming a mother whilst attempting to assert herself as an independent woman, an academic, and writer.

In her later novel, The Pure Gold Baby, published in 2013 but set in the 1960s, her protagonist Jess is a single-mother, similar to her earlier Rosamund in The Millstone. The child Anna has special needs, however the specifics of this are deliberately absent from the narrative. The book covers a lot of ground; from Jess’s own affairs, academic success (she is an anthropologist); to the cost of urban redevelopment and the absurdity of modern life. It ultimately asks the reader to consider what constitutes a worthwhile life.

The short stories in Drabble’s A Day in the Life of a Smiling Woman are (in my opinion) some of her best work. When I encountered an ex-library copy of the book, reading straight through the collection from beginning to end, I found myself thinking that she had touched on all facets of the reality of women’s lives in the modern era.

Though it would be incorrect to say that she had utilised just one typically ‘Drabbleian’ woman throughout the stories, I feel that her trademark was fully present.

The stories could in fact be grouped together in their subject matter. In the title story, for example, we see a successful but not confident female TV presenter whose husband is unhappy at his wife’s success, and she, in turn, is exasperated and exhausted by the continuing demands of other people. Finding herself unable to say ‘No’, or to let anyone down, she performs various tasks on behalf of others throughout the day, leading to a discovery at the end of the story that leaves her future uncertain.

In another story, we see a similarly exhausted mother who is taken advantage of by a needy ‘friend’. The friend narrates the story, and Drabble cleverly shows the selfishness of the friend whilst allowing a glimpse of the stretched patience of the mother. In yet another, we have a successful woman who is accosted by a well-known television personality at a party.

Whilst in the later stories, we see older female characters who are striking out, either travelling alone or with partners, but intent on making the best of their later years. Presumably, these may be the younger mothers who have come full circle, as Drabble herself had done.

What is clear from Drabble’s career and that of the other female novelists mentioned here is that, like the title or not, there has remained throughout the decades a readership for the kinds of domestic fiction they represented.

What perhaps critics of this type of fiction may have dismissed as mere ‘novels written around the pine kitchen table’ is the fact that many of them represented the lives of real women.

Yes, some of them are painfully middle-class, white, British lives. But nevertheless, for women emerging into a new era of combining work and the domestic drudgery of family life, they perhaps provided a blueprint for how to negotiate these boundaries.

I operate on a patron model to allow all my writing and research to remain here for free. If you value the work that I do in uncovering the stories of women, and are in a position to support this financially from as little as £2 per month, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you for your support.

Hey, I think this is fascinating. Hampstead plays a large part (huge) in my life. My mother grew up there, her own mother having grown up there too. I went to school there in my turn. Emigré Hampstead was an astonishingly vital and vivid place bringing with it a complexity of mittel Europa and Jewish life, experience and politics, and that vibe and history mixed with a wide range of folk, lingered then and lingers still in its houses and roads and alleys and routes even now though so many of those past generations are gone. In my turn I went to school there. Its streets are like veins of my body. That white middle class British aura is more complex and made up ofvery different strands than it may first appear.

So, I do think there is a spirit that kind of hovers over the novels and novelists under its aegis. For my money, Penelope Lively and Gillian Freeman (seek her out…your efforts will be oh so wonderfully rewarded) are my go tos, just ahead of Drabble (I would never say Byatt was a Hampstead novelist…too Tory, too intellectualised so, to me, tipping over into cleverness for cleverness sake). I think I find it difficult to get over my awe of Drabble…

And…I dig that photo. @Arnie Bernstein had posted it on one of his typewriter Notes recently and I replied saying how wonderful a photo of a writer at her typewriter it is, how cool she is, how concentrated, how you can almost see the words and story leaving her brain and passing down her arms into her fingers and onto the keys of that stylish typewriter. And, all in the domestic context of her house. It could be a votive.

Lovely piece, Kate, lovely.

Wow. "It is clear from the photograph that she is working amongst the detritus of the family home."

This hit hard! :D Always surrounded by the aftermath of daily chores and trying to get some reading and writing done. That photograph is Drabble is exactly how I picture women writing despite everything. I just read your Byatt piece. Also, what is wrong with ‘middle-class orgasms, delicatessen food and high thought’? It sounds to me like an anti-criticism. I'd love to know more on this because am not well-versed in this topic.