Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

There have always been various reasons that women writers have chosen to write under a pseudonym.

One reason, of course, is that it was often more difficult to achieve publication as a woman. The Brontë sisters, for example, were first published under the collective names of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. This ensured the publication of their first poetry collection, and paved the way to their later novels. They were also reportedly shy, likely due to their seclusion within the West Yorkshire village of Howarth, following the death of their mother Maria.

“We did not like to declare ourselves women, because we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.”

Charlotte Brontë

Mary Ann Evans, meanwhile, writing in the mid to late 1800’s, a time when women authors struggled to be respected as much as their male counterparts, chose a wholly male name - ‘George Eliot’ - in which to write her famous novels. In fact, so successful was this pen name that this is one pseudonym that has stuck.

Other writers arguably chose to write under a pseudonym when writing in a different genre, and this is something that some novelists still do.

In more recent times, author of the hugely successful Harry Potter series, JK Rowling, already choosing a somewhat ambiguous initialling of her name (perhaps to offer the ‘suggestion’ that she could be male or female, something which irks a little now, given her positioning in the anti-trans rights field), then chose to write under Robert Galbraith for her Cormoran Strike adult detective series, likely wishing to try out something new without the prejudice of her previous work.

Louisa May Alcott, most famously known for Little Women, wrote under the name of Flora Fairfield before her novel became a success, and Agatha Christie wrote six novels in the romance genre under the name of Mary Westmacott. The forename taken from Christie’s middle name, and the surname from some distant relatives, allowed for her to explore a different genre away from the detective fiction for which she was known. Similar to JK Rowling’s adoption of Robert Galbraith, it relieved the expectation for the novels.

Sylvia Plath, meanwhile, wrote her one and only novel The Bell Jar under the name of Victoria Lucas originally. This was likely, in part, to protect her mother as the book is semi-autobiographical, and as such, the mother of protagonist Esther Greenwood does not come across in a very good light.

In 2016, a story broke which rocked the literary world, when Italian journalist Claudio Gatti claimed to have solved the mystery of the real identity of novelist Elena Ferrante.

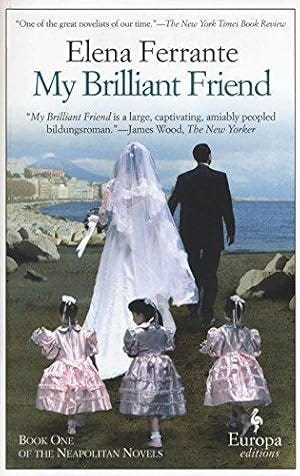

Publishing her first novel in Italy in 1992, but becoming particularly well-known in 2012 after the English translation of the first of her Neapolitan series, My Brilliant Friend, went on sale in the US, Ferrante had always shied away from any publicity of her true identity, openly using the pseudonym as a cover. Gatti’s article featured on The New York Review of Books website, as well as appearing at the same time on French, Italian, and German websites. He alleged that an obscure translator named Anita Raja, who worked in the translation of East German women’s texts into Italian, was the real Elena Ferrante.

What was interesting about Gatti’s ‘big reveal’ was that the uproar that followed the article was largely negative. Many media outlets saw Gatti’s investigation as a violation, questioning the suitability and ethical motives behind such an invasion of the author’s chosen privacy.

Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels surround the lives of two women living in Naples; a female writer, also named Elena - though known as Lenù - and her best friend Lila. Initially, Ferrante stated that she had used the pen-name because she was nervous. She later claimed that she continued to use it as she resented the publishing industry’s insistence on the ‘celebrity’ status of authors, where the publishing of books became more about the writer’s ‘platform’ than the work itself.

However, as an article in Vox suggests, use of the Ferrante name eventually became a part of her artistic statement. This means that fans of the Neapolitan novels not only developed a love for the two fictional female characters within their pages, but also with the idea of Ferrante herself, as someone who was at once familiar, and also removed. The mystery and anonymity provided by the pseudonym allowed for a richer layer and experience of the novels themselves; within their pages, readers felt that the author’s character was also revealed.

“Removing the author — as understood by the media — from the result of his writing creates a space that wasn’t there before.”

Elena Ferrante

Many critics felt strongly that as well as Gatti’s unwarranted and unwanted revelations on the ‘real’ Ferrante, he had also removed this element of her work.

Spending months investigating the accounting statements of Ferrante’s Italian publisher, he discovered that they were paying Raja as a freelance translator at a far higher than expected rate for her purported translation work. He also backed his ‘evidence’ up with the fact that Raja had been making expensive real estate investments; unlikely, he thought, given the relatively low pay of a translator. Raja’s payments apparently also lined up with the dates of the publication of each of Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels.

What was interesting in this case was that readers and critics alike questioned the need for the revealing of this information or investigation by Gatti in the first place. What was there to gain from knowing the true identity of an author they already loved?

“I do not give a stuff who Ferrante “really” is. If I have a right to know, as Gatti argues, I don’t wish to exercise it. Gatti, as far as I’m concerned, has violated my right not to know, while Ferrante protected it.”

Deborah Orr, The Guardian

Gatti counter-argued that the publisher and Ferrante were almost asking for the identity to be revealed by someone, thus creating the mystery around the author, feeding the public’s interest in her persona. But his claim appeared to miss the point: the publisher and Ferrante herself had carefully guarded her identity, and moreover, based on the reaction and outrage displayed by her readership, her fans definitely did not wish for this information.

Gatti, meanwhile, offered the idea that knowing more about Ferrante’s true identity might help for a clearer insight into the author’s work. But his assumptions didn’t appear to provide much backing to this.

“As literary criticism goes, Gatti’s move is not a radical one. It’s regressive.”

Constance Grady, Vox

Writing in The Guardian, Deborah Orr cites the long tradition of women who choose to write under pseudonyms. This, she claims, is a hangover from the expectations placed on women within the domestic sphere, binding them to homes and families and traditional roles. She suggests that although we may be under the impression that such subterfuge is no longer necessary in order to secure a publishing deal as a female writer, in fact, many successful women are often judged on their abilities to balance the demands of both their work and home life.

I have written and discussed before, for example, the ways in which successful working women/mothers (in all fields, from writers, to athletes, to politicians) are often questioned about their parenting abilities (or even why they have chosen not to parent) in ways which evade working men/fathers.

Orr suggests that Gatti, in his insistent investigation and reveal, wished to subject Ferrante to such scrutiny. He wished, she asserted, to ‘see if her creative life is a suitable match to her domestic life’.

Could it be that Gatti, recognising a woman writer who has eclipsed all other Italian authors of her generation in terms of sales and popularity, wanted to put her back in her place? Expose her as some kind of trickster?

Orr seems to suggest so based on his further revelations in a second published piece. Within it, Gatti writes about the translator Anita Raja’s real-life mother, a holocaust survivor. In this, he appears to suggest that the author Ferrante was disrespectful in her invention of a new name and suggestion of a Neapolitan background, rather than writing about the uniqueness of her real mother, the holocaust survivor. He moreover appears to suggest that this was somehow underhand; that she was tricking her readers by denying her past (let’s not forget: there has not been a confirmation of who Ferrante actually is here; these are all his assumptions, based on the ‘evidence’ of Raja’s earnings from translation).

What this suggestion of Gatti appears to do is likely exactly why Ferrante chose to remain silent about her true identity in the first place: that there are still some men out there who take it upon themselves to put women back in their place. To tell them what and who they ‘should’ be writing about; what is ‘suitable’ material for their work.

Emily and Anne Brontë likely knew this, over 200 years ago. Both of them wrote characters and stories which would have seemed unseemly for a young lady at the time. Emily, in her only published novel Wuthering Heights, gives us a violent and wholly unsuitable character in Heathcliff, only for her central female protagonist Catherine to fall in love with him. A truly toxic romance, if ever there was one.

Anne, meanwhile, in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, shows a female protagonist who avails herself of marriage to an abusive alcoholic and begins a new relationship with a young farmer as a single parent. Even their own sister, Charlotte, tried to edit and apologise for what was considered her siblings’ subversiveness.

What appears to have happened following Gatti’s revelations is very little: the claim that the author was in fact the translator Anita Raja has never been verified. Ferrante’s novels are still as popular as ever (My Brilliant Friend recently placed number one on the New York Times ‘Best Books of the 21st Century’), and her reader’s don’t appear to care about her true identity.

In fact, as evidenced by the outcry against the revelations in 2016, they are staunchly in favour of her mystery identity remaining just that.

In an era which views popularity in the sharing of increasingly personal information on the internet, as well as the status gleaned from how many likes, shares, or followers a person gains, I find Ferrante’s choice to continue to write her novels, eschewing fame and celebrity, somewhat refreshing.

Free subscribers receive my weekly researched essays every Sunday, as well as access to community threads.

Paid subscribers also receive access to my monthly reviews and full archives. A paid subscription works out at less than £2 per month for the yearly fee, helping me to research and celebrate the important words of women.

Thank you for your support 🙂

I haven't read her books yet although they are on my short list for next year. I think the use of a pseudonym is perfectly fine and adds to the mystique. It is a personal choice of the author and is a tool that has been used for centuries for various reasons, artistic or otherwise. More power to her, whoever she might be!

I love Elena Ferrante’s work - mostly through the Neapolitan series, but I have read some of her other books, too. I think it’s actually quite wonderful and freeing to be able to read them without having to reference the author’s background. I like being able to enjoy and appreciate art in and of itself and not needing to dig deeper. There is enough deep mess in the words for a lifetime of digging.

I also agree that there would definitely be a tendency to look at whether her life gave her the ‘validity’ to write what she wrote. Could she write about leaving her children if she never had children? Could she only write about abuse and violence if she had experienced it? And so on.

And the power of not having to buy into building a platform, and performing outside of the words she writes? Wonderful! Would that we all had that.