Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews of great books and recommended reading, please consider a free or paid subscription.

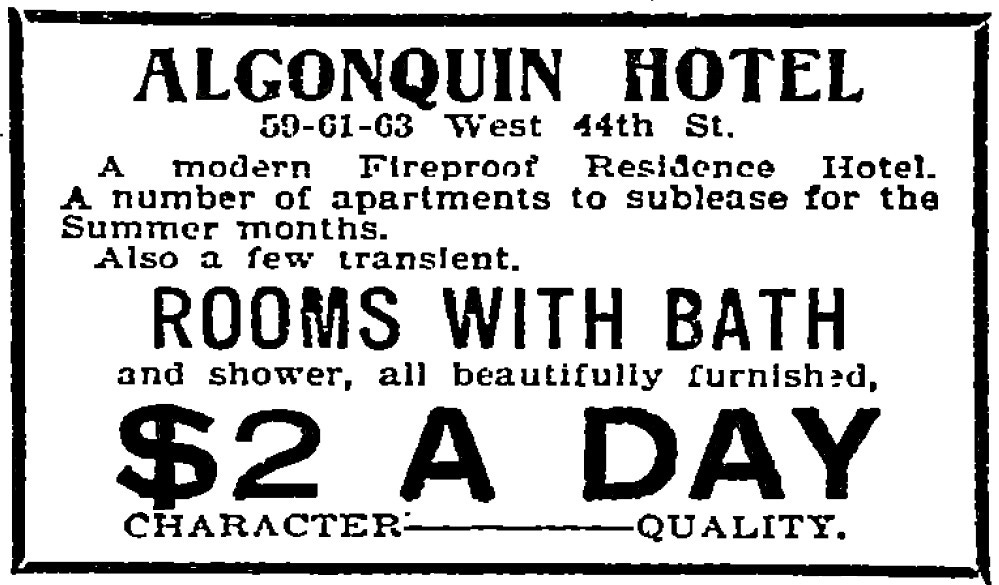

In 1919, an informal group of writers, artists, journalists and playwrights began meeting at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City, where, seated at a large round table, they would enjoy lunch and conversation every weekday throughout the 1920’s and 30’s.

It began when a number of writers met up at the Hotel on 44th Street and, enjoying themselves immensely, simply continued to repeat their experience the following day, continuing until the lunches became a weekday ritual.

This group, becoming known forever after as the Algonquin Round Table, were made up of some of the most successful literary minds of the day.

They included Dorothy Parker, Harold Ross (Founder of the New Yorker), Harpo Marx, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Robert Benchley, Robert Sherwood, George S Kaufman, Franklin P Adams, and Marc Connelly, amongst others. They became celebrated throughout the 1920s for their lively, witty conversation and urbane sophistication. Although the members of the Algonquin Round Table eventually went their separate ways, the last meeting actually took place as late as 1943.

The period these members began their daily meetings came on the heels of the First World War, a time of gaiety and optimism for many, which sparked a new era of creativity in US culture. The dozen or so who lunched at the Algonquin became known as legendary taste makers within this newly emerging culture, recognised as much for their outrageous comments as they were for their artistic work.

The original, regular core of writers were occasionally joined by others, such as the playwright Noel Coward and actress Tallulah Bankhead, but it remained essentially the original core group of friends, who held a shared admiration for one another’s work. The friends’ outspoken and often outrageous comments often made it into one another’s daily columns in the press.

Edna Ferber, an attendee at the meetings, once referred to them as“The Poison Squad,” stating that:

“They were actually merciless if they disapproved. I have never encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done, they did say so publicly and whole-heartedly.”

The group’s standards were incredibly high: intelligent, with an excellent vocabulary and quick witted, they also had to be tough to endure the same wit reflected back at them. Some of the members became close enough to collaborate on joint projects, such as George Kaufman, who teamed up with Edna Ferber and Marc Connelly on some of his stage comedies, and Harold Ross, who infamously hired both members Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley as book reviewer and drama critic respectively.

The fame of the Algonquin Round Table grew, and by 1925, what had begun as a small, private clique was now a public amusement, with many becoming attuned to the members’ opinions. People attended the Algonquin simply to watch them during their lunchtime meetings, with some of the original members becoming strained by the constant attention of the public. Subsequently, Roberts’ Benchley and Sherwood left the group in order to focus on their work, and in 1927, a controversial execution of two Italian immigrants, Sacco and Vanzetti, divided the group members.

Dorothy Parker, one of the group’s key female members, had believed strongly in Sacco and Vanzetti’s innocence, stating following their execution:

“I had heard someone say and so I said too, that ridicule is the most effective weapon. Well, now I know that there are things that never have been funny and never will be. And I know that ridicule may be a shield but it is not a weapon.”

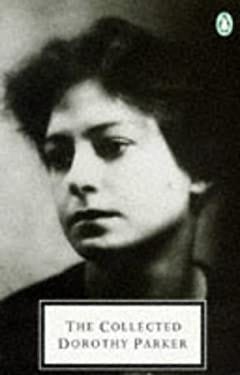

Dorothy Parker (nee Rothschild) - also known as ‘Dot’, or ‘Dottie’ - was born in 1893 in West End, near Long Beach, New Jersey, and was a talented short story writer, as well as poet, screenwriter and, perhaps most famously, critic. Known for her witty and often acerbic comments, she was a key member and one of the original founders of the Algonquin Round Table.

“If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style. The first greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they're happy.”

Parker was initially employed as a member of the editorial staff at Vogue from 1916, though left for Vanity Fair a year later, working for them as a drama critic. The same year she married Edwin Pond Parker II, later divorcing him in 1928 but keeping his name.

“I require three things in a man: he must be handsome, ruthless, and stupid.”

Unfortunately, Vanity Fair didn’t favour her acerbic wit and she was summarily discharged from her role there in 1920, leading her to make her way as a freelance writer.

Turning her hand to poetry, Parker’s first book of verse Enough Rope was released in 1926. It is a light and witty collection, with some cynical undertones thrown in. She published two later collections, Sunset Gun (1928) and Death and Taxes (1931), which were collected with Enough Rope in Collected Poems: Not So Deep As a Well (1936).

Parker began reviewing books for The New Yorker in 1927 under the moniker “Constant Reader,” and she became known as an associate of the magazine as a staff writer and contributor for most of her career.

Because of her position at The New Yorker coupled with her time at the Algonquin, Parker was recognised as a great conversationalist with many famous writers and journalists who followed, such as Nora Ephron. In fact, her reputation was so well established, that famous quotations and quips were often attributed to her regardless, simply due to her reputation. For young writers starting out such as Ephron, she came to epitomise the image of the 1920’s liberated woman.

But her work wasn’t just a matter of acerbic snipes: in 1929, she proved her writing capabilities and talent by winning the O. Henry Award for her short story ‘Big Blonde,’ a tale about an ageing party girl. Her short story collections, Laments for the Living (1930) and After Such Pleasures (1933), were combined in 1939 as Here Lies. All of Parker’s poetry, reviews, and short stories were then collected together in one volume, which I wrote about in this essay.

Through both her stories and poems, Parker uses a tragicomic voice to express the frailties of the human condition.

“I don’t care what is written about me so long as it isn’t true.”

A new artistic endeavour opened up for Parker in 1933 when, with her second husband Alan Campbell, the couple of newlyweds went to Hollywood to collaborate on film scripts. They went on to receive screen credits for over 15 films, including the Academy Award winning A Star is Born. She also became involved in left-wing politics, going on to report from the Spanish Civil War, as well as adding Esquire book reviews and play scripts to her name.

Parker made her home in Hollywood until the death of her husband in 1963, when she returned to New York City, living until her death in a residential hotel. In later life, she appeared somewhat critical of the Algonquin literary group that had garnered her such a reputation, suggesting that:

“The Round Table was just a lot of people telling jokes and telling each other how good they were. Just a bunch of loudmouths showing off, saving their gags for days, waiting for a chance to spring them...There was no truth in anything they said. It was the terrible day of the wisecrack, so there didn't have to be any truth…”

Dorothy Parker died in 1967 at the age of 73, bequeathing her estate to Martin Luther King and the NAACP.

Sadly, her ashes apparently remained unclaimed until 1988, languishing in her retired lawyer’s filing cabinet. After 17 years, her lawyer’s colleague, aided by the celebrity columnist Liz Smith, finally brought this to public attention, whereupon the NAACP claimed them and created a memorial plaque stating Parker’s own words:

“Excuse my dust.”

The meetings of the Algonquin Round Table had begun to lose their lustre as the 1930’s Great Depression era loomed, but the legacy of the wisecracking writers, artists and intellectuals it garnered remains to this day, with the hotel still receiving guests and tourists, eager for a tour of its famed round table.

If you’re new around here, I usually write about all things women literature related. My paid subscribers also receive a monthly review of great books and recommended reading. Please consider a free or paid subscription - your support helps keep this newsletter afloat!

On my way to Trinity College of Music on Mandeville Place as a student in the late 70s, I remember coming across Dorothy Parker's words graffitied on a wall: Razors pain you/Rivers are damp/Acids stain you and drugs cause cramp. Guns aren't lawful/Nooses give/Gas smells awful/You might as well live.

I may not have remembered it accurately - I went past the same wall every week for a month or so - but it made a powerful impression on me.

As Renee commented, her later life view of her younger self is interesting. And how sad that her ashes remained unclaimed for such a long time. Thanks, as always, Kate.