Swift, Shelley, and the Gothic Tradition

Why it's important to celebrate all women artists

Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

A recent article on The Conversation by Matthew J.A.Green, Associate Professor in Literature and Popular Culture at the University of Nottingham, comparing Taylor Swift (favourably) to some of the Gothic greats (Mary Shelley, Ann Radcliffe and Bram Stoker) has been doing the rounds. Here it is if you missed it.

Well, it appears to have caused the inevitable consternation (including here on Substack), as was likely the intention of Professor Green. It seems that everywhere you look, someone is complaining about Taylor Swift. That a (male) professor was actually celebrating her was something of a pleasant surprise.

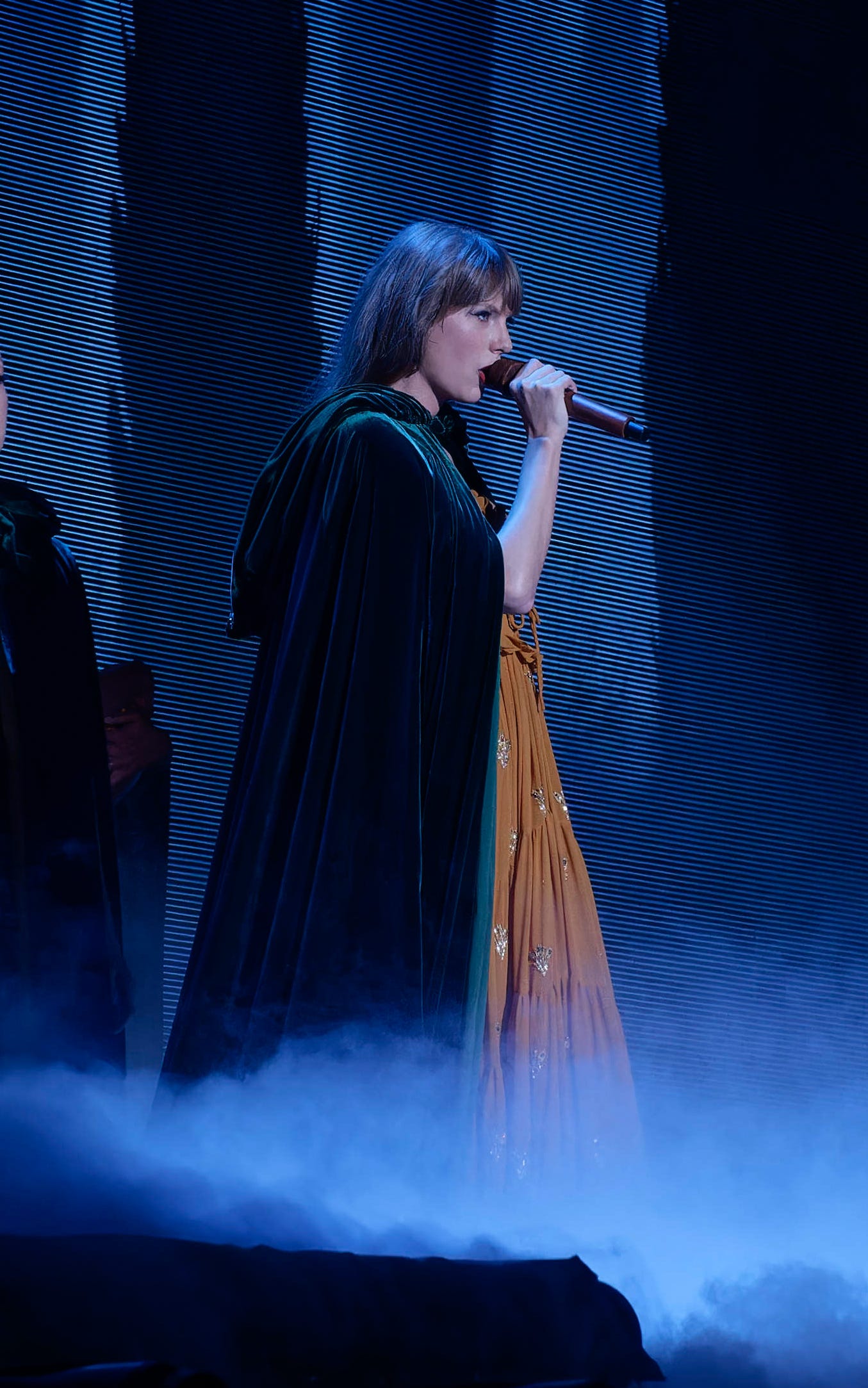

In his article, Green draws on Swift’s “extensive use of Gothic elements to engage her audience and articulate her feminist politics.” Not just evident in her lyrics, he points to the elaborate set designs containing Gothic art, and her costumes, which he claims “transform images of monstrous femininity,” including the witch, the lamia, and the madwoman, thus transforming them “into symbols of empowerment.”

Interestingly, Green points to Swift’s use of such imagery within her work and Eras tour as demonstrating both the pervasiveness and renewed cultural relevance of the Gothic tradition.

I think this is a key argument within Green’s claims of the relevance of Swift in connection to the earlier icons of the Gothic tradition: if we want to encourage younger women to pick up the works of such trail blazers as Mary Shelley, is it not a positive thing for her traditions to transcend into the popular medium of music such as Swift displays?

As Green is keen to point out, these earlier Gothic writers used their writing to probe deeper questions around gender, power, and personal freedom. Similarly, and although Swift has a level of popularity unthinkable to such women as Shelley during her own lifetime, she nonetheless continues throughout her work to pursue questions of female identity, acceptance, recognition, and gender politics.

I can think of no other current musician who faces such scrutiny of her personal and professional life. Recent articles have even included the questioning of her ‘suitability’ as a role model for young women as she is a “childless cat lady.” (Unsure why this is even seen as an insult, tbh…).

On her 2024 album The Tortured Poets, Swift ventures towards the Gothic within her song lyrics. She has also in the past based songs around other literary figures and genres, including the poet Sylvia Plath.

Swift’s career started at the age of ten when she performed at local events, invited to sing the Star-Spangled Banner at a Philadelphia 76ers basketball game at the age of 11, and picked up a guitar to begin writing her own songs at the age of 12.

At the age of 34, she has more than earned her credibility as a songwriter, musician and performer. Yet, she continues to face criticism from all quarters, particularly the misogynist element she receives on a daily basis, including deriding her for her clever marketing and branding.

Whether this makes her as ‘important’ as the likes of the Gothic traditionalists such as Shelley is another question, of course. But what I think is interesting in the arguments vehemently against the comparison is that many reference the difficulties faced by Shelley of acceptance within the literary canon as well as her ahead-of-her-time ideas around science.

What I think is lost in this debate is the fact that both have suffered as women artists from the age-old patriarchal view of their ideas and art. Just because Swift is a hugely wealthy and popular example of her craft doesn’t negate the talent and hard graft she has had to put in to be there. Not just in her work ethic throughout her two decades of making music, but in overcoming the negative press she has received to go with it.

Admittedly, Swift is not discovering new ideas around science or being the first to encapsulate a new genre within her work.

However, what she does do very well is utilise earlier traditions and blend genres in order to create her own sound. She represents the difficulties of love, friendship, identity, and the struggle to maintain a place in the world as a woman. She also famously took control of her own back catalogue and has not been afraid to speak up and criticise the gatekeepers of the music business. Criticism that she is merely ‘popular’ misses the point: Swift is popular for her views and lyrics on misogyny now because we live in a more accepting culture, in which social media and streaming platforms allow for women’s words to transcend the gatekeepers. Mary Shelley, alas, did not.

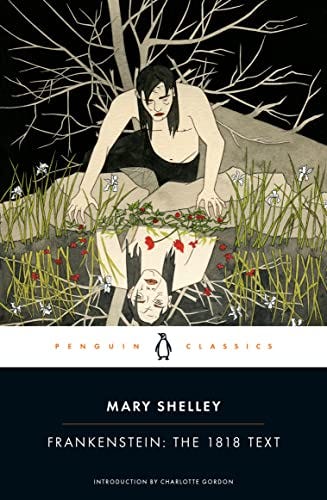

Shelley’s seminal work Frankenstein, often credited as the first science fiction novel, was assumed to be the work of her paramour, Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her writing has often been seen as a feminist critique of science. Like Swift, she too was young when she penned her most famous work at just eighteen years of age.

In her personal life, she reportedly lost her virginity on her mother’s grave, as well as eloping to France with the married poet Shelley at the age of 16.

In fact, it could be argued that if Shelley was alive in the 21st century, she may have reached a more ‘popular’ level of notoriety through her work, but, like Swift, her personal life would most certainly have made the front pages.

Professor Green also makes connections to Ann Radcliffe, author of The Mysteries of Udolpho, suggesting that her work contains reference to medieval Europe in her explorations of female subjectivity during a time of political, economic, and intellectual upheaval. Radcliffe utilised these ideas to question gender and humanity within her work.

Swift, meanwhile, Green claims, utilises the Gothic tradition in her work to explore gender and subjectivity, having the one advantage over her predecessors: “the power of her music to enhance the emotions and sense of self through audience participation.” He draws on the experience of the recent phenomenal success of the Eras tour, which creates “an almost unprecedented feeling of community and acceptance.”

As Professor Green asserts, apart from Swift’s development of the Gothic literary tradition, her critique and use of feminist biography coupled with her success and loyal fans allows her to directly address her audience to question their ideas around selfhood and culture. This, he claims, allows for a consideration of the significance and profundity of her work as being as ‘important’ as that of the earlier proponents of the Gothic tradition.

This may cause debate amongst ardent supporters of the genius of earlier writers such as Mary Shelley and Ann Radcliffe. But what I think is inherently important from Green’s piece is that young female fans respond to Swift’s words and imagery in a way they may not connect with a writer of the nineteenth century. Moreover, I think the more important point from this is that a new generation of women can come to the ideas, literature, and art of earlier traditions through the lyrics of musicians like Swift, hopefully then going on to seek out these examples of great literature for themselves.

Many British schools now have Frankenstein on their GCSE syllabus. When I was studying for my own exams a million years ago, only texts by male writers were offered. I couldn’t recognise myself in much of the literature I studied, and would have loved to connect with texts like Shelley’s, Radcliffe’s, and Plath’s. But I still might have felt more attuned to pick them up as a teenager if I heard my favourite musicians referencing them first.

I looked up to the iconic pop star Madonna in the 1980s. If she had been singing about ideas from Ariel, for example, I’m sure I would have been devouring Plath’s work earlier than I eventually did as an adult. I might have found more to reflect my own developing identity as a young woman through the words of Plath’s The Bell Jar than I ever found in Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

A few years ago, a friend approached me to help with her teenage daughter’s struggles at reading Frankenstein. She claimed that, as a non-enthusiastic reader, she just couldn’t relate to the text, which was required reading for her upcoming English literature exam. If I could have pointed her towards a medium she did relate to - music and video - I might have been able to persuade her of the relevance of Shelley’s ideas in a modern context.

Similarly, I remember hearing Kate Bush’s Wuthering Heights for the first time and wanting to find out more about the Brontë sisters. I avidly read the novel, and it has remained one of my favourite texts ever since, leading me to a deep fascination with the sisters’ lives and writing.

I am not a teacher, but surely, such cultural comparisons can aid in the teaching of literature to students who may not have the natural inclination towards the study of texts that feel irrelevant or remote from their experience of the world.

Popular music has often borrowed from earlier literary traditions, whether through the retelling of stories or songs which reference specific literary works. The 1970’s song ‘The Wizard’ by rock band Black Sabbath, for example, is based on the character of Gandalf from The Lord of the Rings, whilst three of heavyweights Led Zeppelin’s songs, including the hugely successful Stairway to Heaven, reference Middle Earth.

What I would be willing to bet is that their introduction to their fans of such works led directly to some of their number picking up the texts that they otherwise might not have encountered.

Whichever side of the fence you sit on with such comparisons on the work of artists, I think the key here is that we need to celebrate the enormous achievements of all female artists, particularly ones of the past who often went without the praise and acknowledgement they deserved.

That their ideas and words are still influencing art and culture now is a true testament to their value. And that someone as prolific and successful as Taylor Swift can utilise her platform to expand on the universal messages contained within such works, bringing them to a wider audience as a way to keep these former paragons of literature alive, is no bad thing.

Free subscribers receive my weekly researched essays every Sunday, as well as access to community threads.

Paid subscribers also receive my monthly reviews, where I delve into great reading, writing, and watching. A paid subscription works out at less than £2 per month for the yearly fee, helping me to research and celebrate the important words of women.

Thank you for your support 🙂

A wonderful balanced piece that really shows the cultural impact and reach of Taylor Swift.

This is a brilliant comparison! I personally don't like pop/country music so I wouldn't exactly call myself a Swiftie.. BUT I'll always celebrate and defend Taylor's work. She's tapped into such core elements of the female experience and writes about them in a way that resonates with millions of young girls and women worldwide.. she's so successful and so deserving!