Scaffolding

Lauren Elkin's novel explores themes of desire, generational trauma & feminist politics in the heart of Paris

Welcome to a narrative of their Own, an essay newsletter discussing the lives and literature of women.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews of great books and recommended reading, please consider a free or paid subscription.

I have just finished reading Lauren Elkin’s debut novel Scaffolding and I cannot stop thinking about it.

Although Elkin has previously written several successful nonfiction books, including the phenomenal Flȃneuse and Art Monsters, both of which have featured in my own essays here on Substack, Scaffolding is her first attempt at a work of fiction. And wow, does it deliver.

I had planned a different essay for this week, but after turning over the last page of the novel last night, and then going back through the book to look at the many turned back pages and pencil annotations I had made, I just had to think about it some more. When I think, I write, and so here we are.

The novel centres around the stories of two women: Anna, a psychoanalyst working in the framework of Lacan and living in Paris in the present day (or at least up to 2020), and Florence, a student and feminist living in early 1970’s Paris. The central connection between the two women are that they both occupy the same Belleville apartment in Paris at different times, as well as their shared interest in psychoanalysis.

There is also a third woman, Clèmentine, a young feminist living in the apartment building who befriends Anna. The novel’s title comes from the scaffolding that is being erected over the Paris apartment building during its ravalement; a French word which translates to ‘facelift’ or ‘restoration’ in English. It refers to the process of improving the appearance of a building, for example cleaning or renovating the facade.

The book opens on Anna as she struggles with the grief of suffering a recent miscarriage, whilst her husband David is living in London, having taken a job working on Brexit. He returns to Paris for some weekend visits, and wants Anna to sell the apartment and come to London with him. She, however, is reluctant to leave and instead plans a renovation of the kitchen, where she wishes to remove the 1970s decor (put there by Florence). She also feels unable to return to her work as a psychoanalyst and fears that she cannot cope with her patients coming to the apartment, wishing to keep her office for herself. She attends regular sessions with her own analyst, Esther.

Meanwhile, she befriends Clèmentine, a young feminist who has moved into the building with her boyfriend. Anna and Clèmentine become friends and share many intense conversations on, amongst other things, Lacan, art, relationships and desire. Despite living with her older male partner, Clèmentine confesses to Anna that she finds women attractive, has had relationships with other women, and is occasionally still having encounters with women. She professes an open attitude to monogamy and desire but Anna cannot understand why her new friend is in her current heterosexual relationship when she clearly loves women.

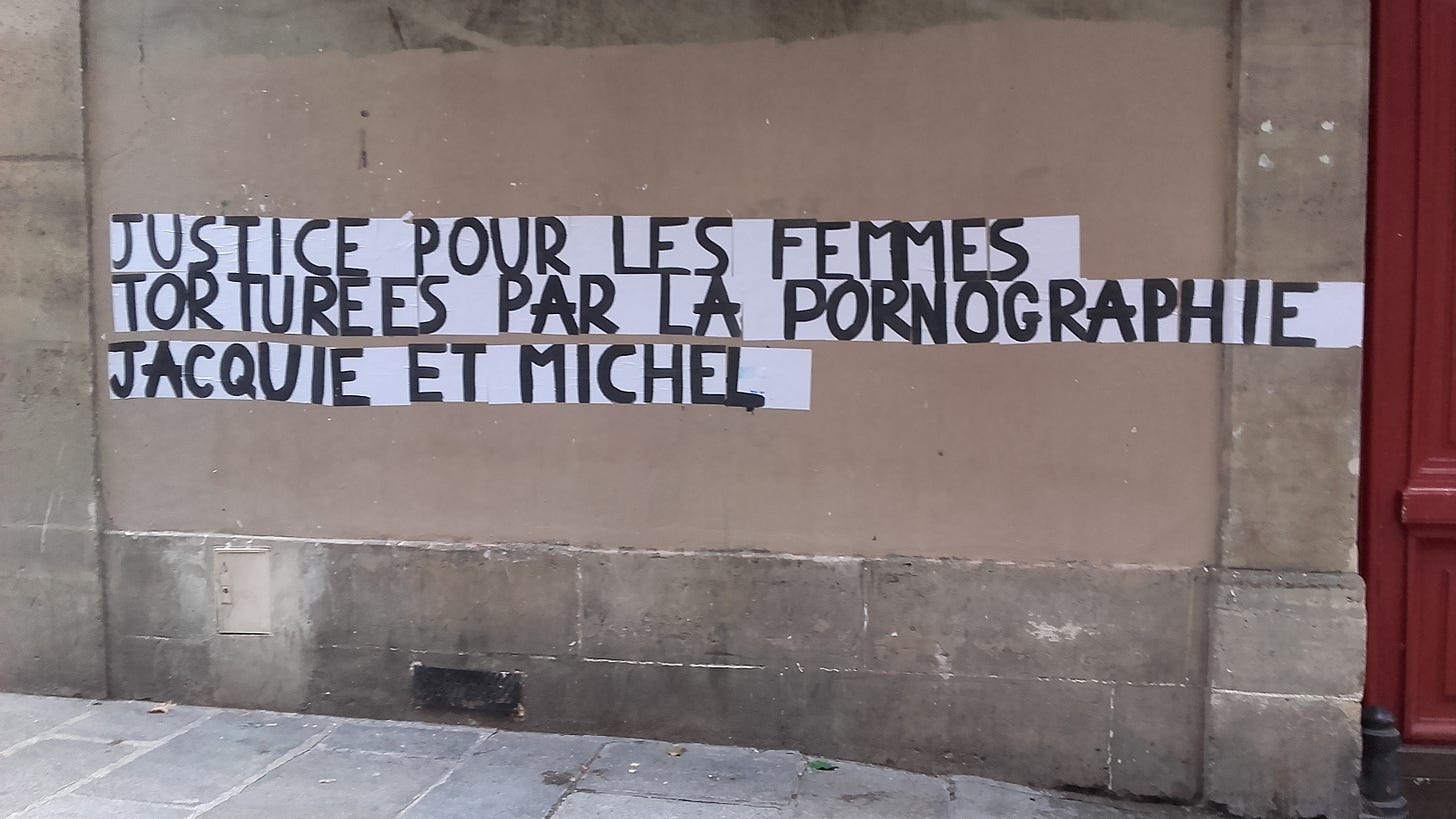

Clèmentine is also involved in what was known in Paris in the 2020’s as Les Colleuses – the Gluers – feminist activists who found a simple, cheap and effective way to make women’s voices heard. Putting up posters in the city was an illegal act, and soon drew attention around the world with slogans such as: "She's not dressed as a slut. You think like a rapist," and "Women are screaming. The state remains silent".

Started by Marguerite Stern, a 29 year old feminist, it quickly became a copycat campaign, reaching as far as China. The groups’ protested the alarming rise in the rates of violence against women, as well as the casual attitudes to catcalling and sexual assault on the streets of the city.

Stern, a former member of the feminist activist group FEMEN, came up with the idea for the street posters to highlight the increasing cases of femicide. Shocked whilst living in Marseille by the 2019 killing of Jule Douib, a 34 year old mother of two who was shot dead in her own home by her abusive ex-partner, Stern took action. It was claimed that Douib had reported her ex to police five times prior to her death but no action was taken against him.

Stern initially began putting up posters denouncing violence against women in Marseille, but moved to Paris later where she set up a collage collective, in the early days becoming known as “Collages Contre les Féminicides” (collages against femicide), initially pasting the names of women killed by current or former partners.

Their activism spread to other cities in France, which reportedly had one of the highest rates of femicide in Europe, and then to many countries around the world. Some of the women affected by violence also took part, using the posters as their platform to answer back to their abusers. Although the term femicide is often used to define the murder of women by men, it is generally used as a French term to refer to the murder of a woman by an ex-partner or family member.

Elkin cleverly weaves this campaign into her novel and it provides an interesting and provocative backdrop to the narrative, particularly in consideration to the recent Pelicot trial. But the women at the centre of the novel are not victims of violence themselves, and this is not a book about the victims of abuse but one of complex human relationships and female desire.

Anna is increasingly attracted to Clèmentine, which surprises her as she has never been attracted to women before, finding the younger woman’s magnetic aura and zest for life and for fighting for what she believes in fascinating.

Anna is also obsessed with the memory of an earlier relationship which ended abruptly. Her ex-boyfriend ended the relationship due to Anna not being Jewish like himself. Because of the generational trauma handed down through his family related to the death of family members in the Jewish death camps, and his inability to speak about the past or his difficult relationship with his father, he struggled with the idea of being ‘French’ and of dating someone who cannot relate to his family’s experience. Both the Jewish experience and the fraught relationship many felt at their treatment in France is another large theme threaded throughout the book, as is that of generational trauma.

“...as the revisiting of a trauma that is impossible to face during the daytime. And in the case of my grandmother’s, one so strong that it has perpetuated itself down the generations.”

The book is also largely about female desire and these ideas in the novel appear to stem from Anna’s interpretations of Lacan’s theories, namely that desire is a fundamental human condition driven by lack, and expressed through fantasy. It was a core part of Lacan’s psychotherapy.

I listened to an interesting interview with Lauren Elkin on the London Review Bookshop Podcast on the writing of the novel, in which she discusses her own interest in Lacan’s theories as a young woman and the ways she utilised this to inform her writing. Amazingly, she also speaks about how, as she works as a translator of texts herself, (in particular on the work of Simone de Beauvoir), Elkin translated the book herself, writing both the English and the French editions. Somewhat modestly, however, she goes on to discuss how she started the book in 2007, claiming that she had many of the ideas but felt too young and inexperienced to write it fully in the early years. I really appreciated this honesty from her as an author, and would guess that the novel that she has now published contains a much richer story and ideas than that which would have emerged had she rushed to publish earlier.

Anna begins two sexually charged interactions during the course of the novel (I don’t want to give too many spoilers, because I really want you to go and read the book!!) and this opens her up to the many possibilities of desire and relationships.

Meanwhile, the second part of the book (sandwiched between parts one and three) is from the joint point of view of Florence and her husband, Henry, occupying the Belleville apartment in 1973. Many of the themes and situations for the couple mirror Anna’s: Florence wants a baby, whilst Anna has just miscarried; Florence is a psychoanalysis student, whilst Anna is a practising psychoanalyst; and both women are involved in extra-marital sexual encounters.

“I want a daughter, if I’m honest, a daughter I can talk to the way my mother never talked to me, or her mother her. Tell her things, teach her, help her be a girl in the world that hates them.”

I found this second section of the book riveting: Florence’s interest in the Women’s Movement and her blossoming feminist politics (which Henry is bemused by) was of great interest to me. Born in the early 1970s, I am always interested in this time period, when my own mother would have been a young woman and the world and attitudes to sex, relationships and women’s roles were rapidly changing.

“Morning. In the bathroom I go to take my pill, and then I don’t, I drop it in the toilet. I have the right to take it, I think, and I have the right to throw it away.”

The story interchanges between Florence and Henry, and at first, I found it jarring to switch to a male perspective in the middle of a book about three fascinating and strong women. However, I soon came to see why Elkin had chosen this narrative structure, and it ultimately worked really well to tell the couple’s evolving story.

“Sometimes this is wonderful, and I think, this, this is love, to know another person like this, and sometimes this is a problem, like I can’t get any shelter from him.”

Florence wants a baby, Henry doesn’t. Florence is becoming increasingly involved with both a feminist women’s consciousness raising group and her professor, as well as planning to become an analyst. Henry had thought his wife would simply stay at home and cook for him, whilst being content not to have children and happy with his mediocre work role and lack of ambition. He frequently tells Florence when she raises the topic of becoming a mother that she already has a child to look after, meaning himself.

“Who said we’re having a baby at all? He said. The ring was fresh on my finger, but that was the moment it began to feel like it didn’t quite fit.”

But it is clear that change is coming, and Florence is a strong and single minded young woman on the threshold of change.

The third section of the book returns to the story of Anna. After being presented with a bombshell at the climax of part one, the story continues to its eventual conclusion, and we are brought up to date on her life and marriage.

If I have any criticism of the book at all, it is that I would have liked more of the middle section set in 1970’s Paris. I felt that Florence and Henry’s story had more to offer, and I was almost expecting a return to it in part three. The book also contained a lot of referencing to Lacan and his theories, which I knew nothing about or was particularly interested in. For my part as a reader and researcher into women’s narratives, I was more interested in the ways in which Elkin utilises desire and power structures to illuminate the women in the novel.

However, I can see after researching a little more on Lacan’s work that his theories influenced the narrative, and it has made me more inclined to discover more about this. I similarly discovered that Lacan theorised that trauma could be passed down through generations and that it could be difficult to integrate the body and mind after experiencing trauma. When I read this it definitely made sense in the context of Elkin’s book as one of the largest areas of annotation I made within my copy was that of generational trauma and the difficulties in the ability to express these issues. I think I would need to read more on Lacan now to fully understand all the many threads and themes of which Elkin writes.

“It’s terrifying to accept the essential otherness of the people we care for.”

Overall, this book is one that will stay with me for a long while, as I navigate the many themes of interest contained in its pages. I love it when that happens! It is such an intellectual yet accessible book, I would say. One that made me excited to turn the pages, yet having to step away at times to think, to read up on the ideas it brought forward, and to contemplate the ways in which we inhabit the world and our own bodies and minds as women.

Just in case you were thinking of taking out a paid subscription to my newsletter and cost has been a barrier, I have put a 50% discount on a paid yearly subscription up to the 20th January as a recent birthday celebration! You have less than 24 hours left if you want to support the newsletter in this way by following this link.

Thank you, as always, for being here. 😀

This sounds like such a fascinating read! I love it when a book makes you think - and when you can’t stop thinking about it long after you’ve finished it. I bet it would be a good one to re-read at some point, too, to help you further explore the themes. I’ll have to give it a go. Thank you for sharing

If Lacan and his influence on intergenerational trauma remains of interest, I highly recommend reading The Unsayable by Annie Rogers. Her first book, A Shining Affliction, is also good but Unsayable really powerfully conveys this.