'On the morning after the sixties'

Joan Didion's 'Slouching Towards Bethlehem' & 'The White Album'

Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

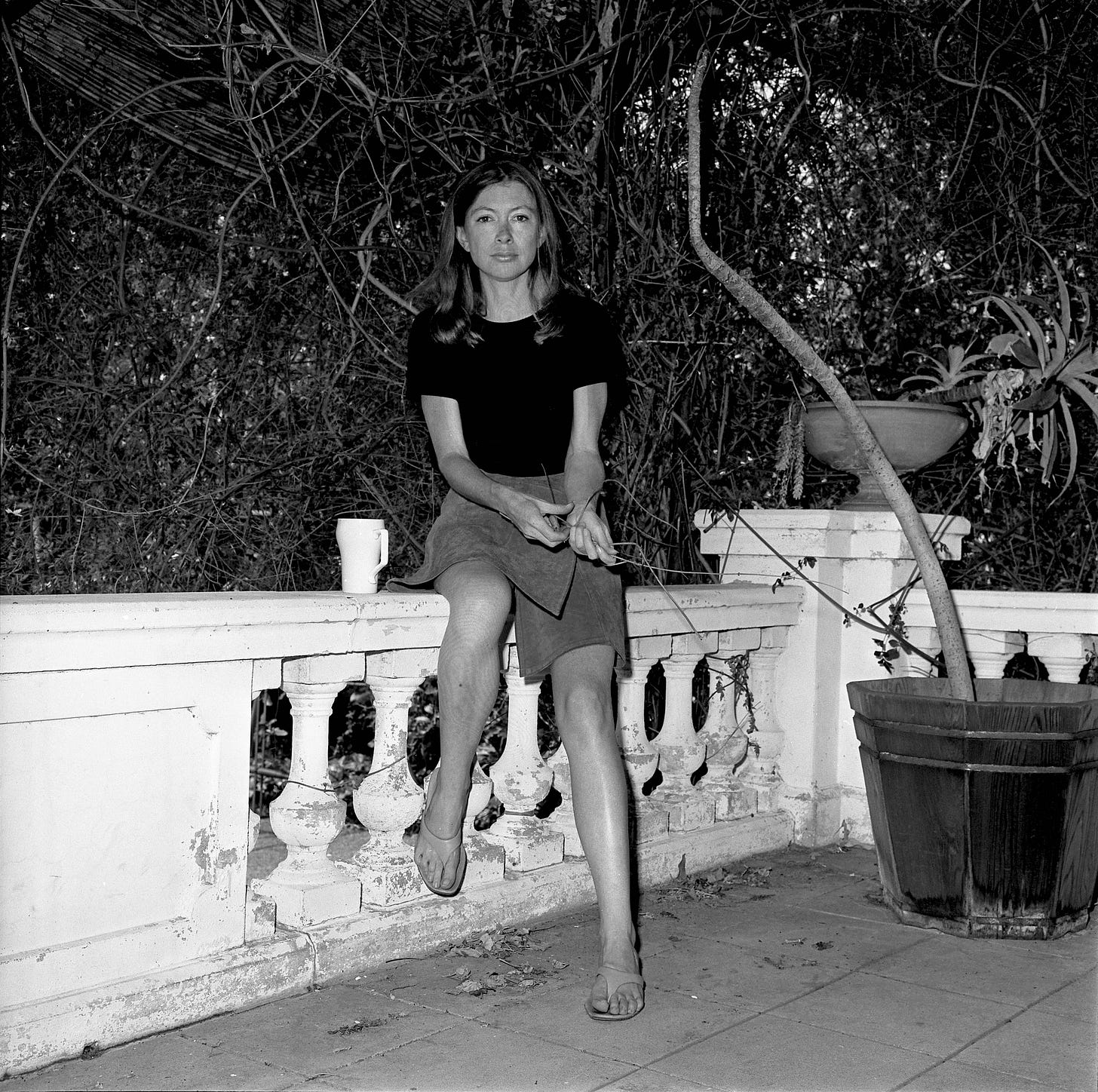

Joan Didion was the quintessential journalist and the woman behind some of the most iconic essays on the counterculture of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Although Didion also wrote successful novels, screenplays, and narrative nonfiction, she was known mostly for her journalism and longform essays, particularly those exposing the underbelly of society and culture around the period. She closely observed and reported on the depiction of social unrest and the fragmentation of society, particularly in the late sixties.

Her most famous writing appeared in magazine articles and columns, and in 1968, several of these were put together to form the collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

In the title essay, which opens: ‘The centre was not holding’, Didion famously wrote about the runaways and ‘hippies’ in the Haight-Ashbury area of San Francisco. She describes the scene in the late spring of 1967, taking herself to San Francisco to witness the worst of the ‘social haemorrhaging’ which appeared to be taking place.

Didion liked to submerge herself within the world she was reporting on. This essay was no exception, although as she states at the outset: ‘I did not even know what I wanted to find out, and so I just stayed around awhile, and made a few friends.’

Taking herself to live amongst the drug addicts and dropouts, the startling result within her essay portrays a cast of misfits, particularly young female runaways whose parents are desperate to find them. Reading it, you can intuit Didion desperately trying to make sense of the life these young people are choosing to live, often days and days filled with getting high and sleeping it off.

‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.’

Arguably, the most startling part of this essay appears when Didion ‘interviews’ a five-year-old girl who is high on LSD. (Didion’s own daughter, left safely at home whilst her mother sought the real story on the streets, was two years old at the time).

Didion is taken to the house where the five year old girl named Susan lives. Sitting on the living room floor, wearing a reefer coat and reading a comic book, Didion says the only thing appearing odd about her at first, as she licks her lips repeatedly in concentration, is the white lipstick she is wearing. The male friend accompanying Didion tells her simply: ‘Five years old. On Acid’.

Susan speaks to Didion, telling her that she is in High Kindergarten and lives with her mother and ‘some other people’. She has just got over the measles and would like a bicycle for Christmas. She engages in a lucid conversation with Didion, where the journalist discovers that her mother has been giving her both acid and peyote for the past year, which Susan describes as ‘getting stoned.’ Didion wants to ask her if any of her friends in High Kindergarten also get stoned, but she confesses that she doesn’t have the words to ask this. A friend of the girl’s mother asks her on Didion’s behalf, and Susan informs them that just two of her other friends also get stoned.

In the 2017 Netflix documentary, The Centre Will Not Hold, Didion is asked how she felt when she discovered the five-year-old drug addict. Surprisingly, Didion’s face lights up at the question: ‘It was gold’, she states. Ever the journalist, eager for the story.

The essay is written in short paragraphs of randomised incidents and conversations Didion has with the inhabitants of the Haight-Ashbury district, which becomes repetitive and hypnotic, echoing the senselessness around her.

The Slouching Towards Bethlehem collection served to establish Didion as a distinguished essayist and confirmed her interests in the disorder of society at the time, as well as explorations of counterculture. Some of her later essays in the 1980s and ‘90s also explored political and social rhetoric.

In her later essay collection, The White Album, published in 1979, Didion returns to the rich subject of the disintegration of society as she saw it at the tail-end of the sixties.

The collection opens with the long title essay which weaves her meeting in the summer of 1970 with Linda Kasabian, girlfriend of Charles Manson, on trial for the murder of five people including Sharon Tate, the pregnant wife of film director Roman Polanski.

Didion meets with Kasabian in prison, even delivering a dress, upon request, for her to wear in court. She confirms within the essay that she met at other times with Kasabian over the years, and was to write a book about her, though this was later abandoned.

The White Album centres around the unease and fear circulating in that year in which Didion and her family lived in a large rented house in Hollywood, an area an acquaintance had described to her as ‘a senseless-killing neighbourhood.’ She references another murder in Laurel Canyon, just a stone’s throw away from the home she was living in with her husband and daughter. She claims to have kept the licence plate details of various panel trucks in the local area in a dressing-table drawer: ‘where they could be found by the police when the time came. That the time would come I never doubted…’.

This follows various encounters with strangers who would either knock at her door - as they had done in the Manson murder case - or she would find them simply standing in her entrance hallway.

‘Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true.’

In 1967, Charles Manson, a young man who had been institutionalised for most of his life, was released from prison. It is reported that he asked if he could remain incarcerated, such was his level of institutionalisation.

He moved to Berkeley and then San Francisco, both cities - as Didion discovered - flooded with young people looking for a new way of life. He amassed a small group of mainly female followers, being a somewhat older figure in the crowd there, and in 1968 headed to Los Angeles in order to pursue a music career. He capitalised on the laxity of social codes in the 1960s, allowing for free-spirited runaways to mingle with Hollywood celebrities.

Manson grew fixated on becoming a star, and made friends with members of the music industry. His band of followers became known as the Manson Family, mostly consisting of young women and girls aged between their late teens and early twenties, inspired by the sixties hippie mantra of “turn on, tune in, and drop out”. Manson used these young women to lure in male supporters, including well-known musicians, settling on a ranch in the San Fernando Valley. Some of the women have later reported that as Manson’s control grew more domineering, he forbade his followers from wearing glasses or carrying money, and often instructed them to take LSD whilst he lectured them on the probability of a race-war. His influence grew as he gained more celebrities to fund his life at the ranch.

It is reported that once Manson realised that his music connections were not going to forward his musical ambitions, he became angry, eventually convincing his ‘Family’ of followers that they must incite violence in the up-scale neighbourhoods of LA due to a bizarre connection he formed between The Beatles The White Album and the end of the world.

In the summer of 1969, Film director Roman Polanski and his wife Sharon Tate rented a house at 10050 Cielo Drive from one of Manson’s former connections.

On the night of the 8th August, four members of the Manson Family attended Polanski and Tate’s home. Polanski was out of town working on a film, and Tate - who was eight months pregnant - along with three of her friends were hanging out there. Despite Manson having no connection with these people, merely a grudge against the previous occupant of the house, three of the members of Manson’s Family killed them all, as well as a teenage friend of the caretakers who happened to be pulling out of the driveway as they arrived. The fourth member, Linda Kasabian, watched on though didn’t take part, and later turned against Manson, securing his life-sentence.

The brutality of the Manson murders, together with the fact that celebrities were targeted, touched upon some of the deepest fears of the American psyche: that you may not be safe, even in your rich homes, and that seemingly ‘good girls’ could be convinced to commit atrocities.

They also indicated, as suggested by Didion in her late sixties essays, the idea that the popular culture of Free Love was not so free after all, and that it was effectively over. Taking both her essay and collection title from The Beatles The White Album, Didion uses the murders to argue that the sixties had effectively ended—“the paranoia,” she wrote, was fulfilled.

Whilst this last essay in my series on women’s writing of the 1960s ends on this somewhat sombre note, it shouldn’t be underestimated how influential the sixties were on popular culture, literature, film, fashion, and music. Many of the freedoms that women continued to strive for began in this era, and continued throughout the oncoming 1970’s Women’s Movement.

What I think Didion and others were increasingly driving at though was that, as with any kind of revolution, there are bound to be extreme elements that arise from such swift changes.

In the case of the Manson murders, it could be argued that the increasingly permissive culture of the sixties had engendered an aura of freedom for young people that perhaps they were not quite ready for. The availability of psychedelic drugs, which became synonymous with the open, ‘Free Love’ culture of cities like San Francisco, together with the mingling of Hollywood influence and money, further added to the crossing of boundaries that had not been seen before. The fact that young people were effectively opting to ‘drop out’ of the societal expectations that their parents had perhaps never questioned, further added to this.

As Didion, ever the journalist chasing the story, showed us: when the boundaries between freedom and over indulgence become blurred, the outcome can be explosive.

Thank you for joining me in the final essay of my series examining the lives and literature of women in the 1960s. If you missed the first two essays, they can be found here and here. You might also enjoy my longer essay on the work of Joan Didion and New Journalism.

Free subscribers receive my weekly researched essays every Sunday, as well as access to community threads.

Paid subscribers also receive my monthly reviews, where I delve into great reading, writing, and watching. A paid subscription works out at less than £2 per month for the yearly fee, helping me to research and celebrate the important words of women.

Thank you for your support 🙂

Names that still stalk our culture and imagination today although we barely remember the story

A five year old kid on LSD? I wonder how they got on it...