Welcome to A Narrative of Their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

If you enjoy reading essays on literature as well as monthly reviews, please consider a free or paid subscription.

“The only way for a woman, as for a man, to know herself as a person, is by creative work of her own.” The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan

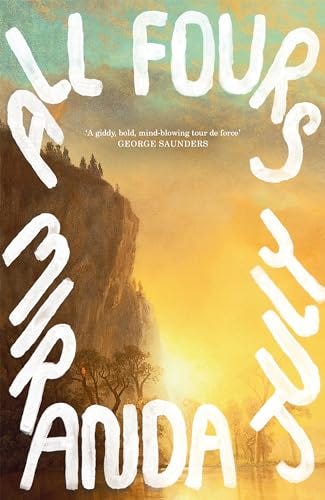

I just finished reading Miranda July’s All Fours, which has been on my radar for a while, not least since reading Petya K. Grady’s review in A Reading Life.

After reading, I felt like I needed to lay down in a cool, dark room for a while. It’s unlike anything I’ve read before. I tried to make connections in my mind (as I often do) with other feminist books, but it really sits in a space of its own. The closest I could think of was Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, or maybe even Claire Dederer’s memoir Love and Trouble: A Midlife Reckoning…but even they don’t really come close to what July has achieved through this book.

On the back of this, I have also been sifting through Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters, in which she initially set out to examine the monstrosity of creating art and female creativity.

As she asserted, quoting the infamous line from Jenny Offill’s book Dept of Speculation, ‘My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead’. Inevitably of course the so-called ‘art monster’ is known to be male and rely solely on a female (usually a wife) to complete all the mundane tasks in life whilst they set about working solely on their art. As other critics have pointed out, Elkin set out to show that female art monsters are less well observed given that this often means choosing their art over mothering, as I looked at in my essay on Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma.

What Elkin found as she explored the subject further, however, was that it was also terrifyingly easy for women to inadvertently become such monsters, and that such ‘bad’ behaviour, often seen as perfectly acceptable in a male artist, or ‘genius’ - determination, rage, ambition - is often considered an ugly and undesirable trait in a woman.

Finding however that her subject matter forced her to place women on the side of the second sex, creating art in reaction to the patriarchy and forcing them to appear ‘Other’, she somewhat changed the stance of her book. Instead, she wrote about the female artists who have placed the body at the centre of their art, utilising their practice to become a language of the body, thereby defining their own aesthetic aims.

As Miranda July’s book is very much about the progression of the woman as artist and self-expression, as well as the female body, these two books merged as I consumed them (and with other reviews I’ve read on All Fours, the word ‘consumed’ really seems to hit the spot on how to encounter this book.)

July’s unnamed female artist narrator is married to Harris and has one child whom they refuse to gender, known only as ‘Sam’. She is constantly working in her garage studio on her art, though it is unclear (both to the reader and herself) what her next project will be. We are told that she is semi-famous and known for her brave forays into the art world, for which she has won prizes.

The first part of the book I found quite strange, and I wasn’t sure where July was taking us.

Embarking on a solo road trip to New York, the narrator, somewhat bizarrely, pulls off the road in nearby Monrovia instead and ends up staying in a motel there for the whole duration of her trip. She does not tell anyone of this plan, other than her trusted best friend and fellow artist, Jordi. The narrator encounters a young man with whom she spends many days of infatuated mutual (though unconsummated) attraction.

Returning home, she struggles to assimilate back into her regular life and marriage, and wonders at why she feels at such an impasse. After a regular yearly checkup with her ob/gyn, she is informed of the term ‘perimenopause’, and discovers that many of the experiences she has been having (insomnia, despair) could be hormone related. This sends her into a further spiral as she considers that, at some point in the next few years, her libido is likely to drop off the edge of a steep metaphorical cliff (and at this point, July shares a graph showing the hormonal drop- not for the faint hearted) thus setting her on a sexual odyssey in which she renegotiates the terms of her marriage and her life as a woman approaching mid-age.

Alongside the reading of these two books, I re-watched the Netflix documentary Feminists: What Were They Thinking? I have seen this twice before, but it never fails to both inspire me and reduce me to tears.

The 2018 documentary directed by Johanna Demetrakas records interviews with women of varying ages and backgrounds anchored around the book of photography ‘Emergence’ published in 1977 and featuring the photographs of Cynthia MacAdams. These portraits capture women embracing feminism during the 1970s Women’s Movement, often posing artistically naked or semi-nude, and tackles themes of identity, the role of the female artist, abortion, race, childhood, and motherhood.

One of the photographed artists, Judy Chicago, speaks candidly about the ways in which she was disregarded in favour of the male artists she trained alongside.

Born in 1939, Chicago explains how she struggled to be taken seriously in a male dominated art scene. She finally got her first retrospective at the de Young Museum, San Francisco in her sixth decade of professional practice.

This exhibition, The Dinner Party, received tremendous reviews and finally achieved Chicago’s lifelong professional goal of revealing the range of her subject matter and technique of her journey as an artist. A month earlier, Thames and Hudson had published The Flowering, an autobiography of Chicago with Forward by feminist pioneer Gloria Steinem.

These two events culminated in a turning point for the ways in which Chicago’s art is perceived.

During the preceding years of her career, Chicago had suffered from challenging and controversial attitudes to her work. She pioneered feminist art and education through a wholly unique programme for Women artists at California State University, Fresno, which continues to develop.

Womanhouse opened in 1972 in Los Angeles as part of the first Feminist Art Program, initially begun at California State. Chicago, alongside her co-educator and artist Miriam Schapiro, worked with a group of art students and local artists to transform a rundown house in LA into the backdrop for a series of installations. During the run of its month-long exhibition, over ten thousand visitors viewed Womanhouse, which was later made into a documentary of its own. It continued to inspire later art works and enabled an expansion of the conversation around the nature of art and the materials considered suitable for artistic expression. The creation of Womanhouse is explored in the Netflix feminist documentary, where other female artists involved with the project explain in tearful and irreverent tones how important the bringing together of female artists to create this vision was.

Becoming Chicago’s most recognised work, The Dinner Party was created between 1974 and 1979 and displays women’s history created with the help of hundreds of volunteers. The multimedia project is a symbolic history of women in Western Civilization, and has received more than one million viewers during its sixteen exhibitions held at venues spanning six countries.

In the early 1980s, Chicago turned her attention to the subject of birth, identifying an absence within Western art. She designed a series of birth and creation images from needlework, completed under her supervision. It was exhibited in more than 100 venues. She also focused on her studio work during this time, completing PowerPlay, a series of drawings, paintings, weavings, cast paper and bronze reliefs to bring a critical feminist gaze to the gender construct of masculinity, looking at definitions of power in the world, particularly male, and exploring her long concern with issues of power and powerlessness. She later turned her attention to her Jewish heritage to create her 1993 Holocaust Project: From Darkness Into Light.

Throughout her career, Chicago has continued her resolute belief that art is a vehicle for intellectual transformation as well as social change. She has continued to support women’s right to make art at the highest level, and has garnered an ongoing respect as an artist, writer, teacher and feminist, showing that art can support women’s right to freedom of expression.

Something else that stood out to me in the Netflix documentary in relation to the texts I have been encountering these past weeks was a sentiment expressed by the actress Jane Fonda.

Describing how she had always enjoyed climbing trees and adventures as a young girl, Fonda explains how, as she grew up, she was constantly being told to be a ‘good girl’. She describes how this sentiment diminished her own personality, saying that if girls are told to be ‘good’, this inherently suggests that they are ‘bad’ if they exhibit behaviour that is in line with their own natural personality. She goes on to touchingly observe that, as she has grown older, she feels that she has finally returned to the young, pre-adolescent girl she once was: fearless, unashamed, and adventurous.

What was interesting was that this same sentiment was expressed in a single line in Miranda July’s All Fours.

The narrator, finally hearing from her doctor that there are many good things around reaching midlife and menopause, puts out a group text asking all the older women she knows: ‘What’s the best thing about life after bleeding?’ She is surprised to receive many fast responses from the women, with a range of positive answers. But the one that jumped out and appeared to coincide with Fonda’s remark was this:

‘I feel like my true self. I’m 9 years old and I can do whatever I want.’

This felt like a connection between all the texts I have encountered in the past couple of weeks: this sentiment of female artists, coming to the realisation that they can be fearless and practise the art - and indeed the lives - that they always dreamed of.

The narrator receives other examples of positive outcomes from the menopausal women, many reiterating the new autonomy and freedom they felt over their own bodies.

‘I’ve contributed 4 people to the world. I’ve done my part. My body is now mine because it can’t be anyone else’s,’ one of the women responds.

What is also interesting is that July refers in her ‘Acknowledgements’ at the end of the book to the series of interviews she conducted with women about the physical and emotional midlife changes they experienced. Although she states that there are no actual traces of the original conversations within the text, she nonetheless reveals that these conversations ‘made writing it more necessary’.

Much has been made of the provocative, sexually explicit sections of the novel, and this is indeed a large part of the text. However, I think to label this as simply a sexual awakening of the female midlife experience is limiting: any woman who comes to July’s book with questions around how to navigate the second half of life - how to exist in this life as a female artist, not necessarily in the limiting meaning of the word, but as an artist of their own autonomy and ambition - cannot fail to walk away from it reeling with the possibilities for the next phase of life.

It is a book that I shall not forget in a long time. It is a book I shall return to and recommend to other women wanting to know the way forward.

It is not, however, a book I shall be passing out to others, as my copy contains too many folded back corners and notes in the margins.

*In addition, if you are interested in hearing more about the book in Miranda July’s own words, I highly recommend checking out her interview with Sam Baker on her podcast The Shift.

Free subscribers receive my weekly researched essays every Sunday, as well as access to community threads.

Paid subscribers also receive my monthly reviews, where I delve into great reading, writing, and watching. A paid subscription works out at less than £2 per month for the yearly fee, helping me to research and celebrate the important words of women.

Thank you for your support 🙂

![Georgia O'Keefe - Black Iris [1926] | This monumental flower… | Flickr Georgia O'Keefe - Black Iris [1926] | This monumental flower… | Flickr](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VYLn!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe1e7c551-fe13-4468-bfe6-5bf57c8db840_813x1024.jpeg)

That phrase Art Monster always reminds me of Nightbitch!

All Fours knocked me off my feet as well. Men have been writing books with similarly “unmanageable” male characters for ages. More public discourse about the freedom in menopause highlights how women experience creativity across the lifespan and phases of partnerships. I appreciate the connections you make to 20th century feminist art movements and Judy Chicago, who explicitly decided to remain child free to focus on her art.