Joan Didion & New Journalism

A new book of interviews reveals the woman behind the legend

‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live’.

Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

This week, in a change from my regular programming, I am sharing one of my favourite newsletters from the archives. The reason for this is two-fold: firstly, it has been a difficult week personally, and so my head has not been in the right writing space to deliver the kind of quality, researched essay that you - my readers - deserve.

Secondly, I am proud of some of the essays I have written over the past year and a bit, and as my subscriber numbers have increased significantly in the past few months, it’s nice to share something from the archives that I think newer readers might enjoy.

Joan Didion is my absolute favourite non-fiction writer, and her book on grief - The Year of Magical Thinking - has been in my mind a lot this week. I intend to return to more of her work on future newsletters, but for now, please enjoy this look at a remarkable woman’s life in writing.

Writing and journalism lost one of its finest proponents last year with the sad death of Joan Didion. A new book featuring Didion’s last interview for Time in 2021, together with eight others ranging from 1972, helps to reveal the woman behind some of the most iconic essays on the counterculture of the 1960s and ‘70s.

For anyone unfamiliar with Didion’s oeuvre, she broke onto the literary scene in the late 1950s. Following her graduation from the University of California, Berkeley in 1956, she initially started out at Vogue magazine where she won an essay writing contest and where she worked from 1956 to 1963 as a copywriter and then editor.

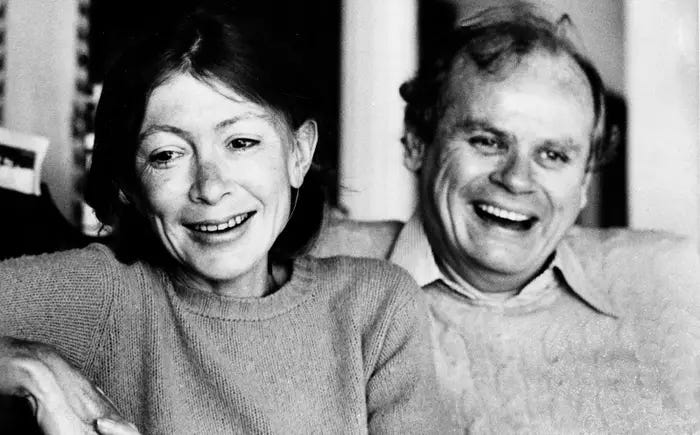

Born and raised in Sacramento, California – a place which featured heavily in her writing - Didion moved to New York to take up her position at Vogue. She met and married her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, whilst in New York and in 1964, they moved to Los Angeles, California, where they remained following the adoption of their daughter, Quintana Roo, for the next 20 years.

Didion was known mostly for her lucid prose, in which she observed and reported on the depiction of social unrest and the fragmentation of society, particularly in the 1960s. But as well as an esteemed essayist, she also wrote fiction. In 1963, whilst still at Vogue, she wrote and published her first novel Run River, which deals with the disintegration of a California family.

Arguably Didion’s most famous writing however appeared in magazine articles and columns, and in 1968, several of these were put together to form the collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem. This collection served to establish Didion as a distinguished essayist and confirmed her interests in the disorder of society at the time, as well as explorations of counterculture. Some of her later essays in the 1980s and ‘90s also explored political and social rhetoric.

Didion’s 1991 essay ‘Sentimental Journeys’, was thought to be the first published to suggest that the Central Park Five, a case where five Black youths were incarcerated for the rape of a white woman, had been wrongfully convicted, and her reporting on the racial profiling and class injustice within New York was brought to the attention of a divided public. The five were later exonerated, suing the state in 2014 for a reported $41 million. In true Didion style, when asked in her last interview for Time in 2021 how she felt when they were exonerated, Didion stated simply: ‘However I felt didn’t get me or them anywhere’.

Her second collection, The White Album, appeared in 1979, continuing her exploration of the turbulent 1960’s, with her later After Henry collection published in 1992, which discussed the decay of the Establishment.

Didion also went on to publish more fiction, including the short novels Play it as it Lays (1970), and A Book of Common Prayer (1977). Didion’s character of Maria in Play it as it Lays is a particularly Didion-esque California type resonant in her work, who is trying to come to terms with the meaninglessness of her experiences in Los Angeles. When asked by The New York Times Book Review about her tendency to write women who are seen as ‘passive drifters who lead purposeless lives’, Didion claims she does not agree, stating: ‘I don’t see that about any women I’ve written about.’ Interestingly, she confirms her unsociability in the interview, claiming to like a lot of people, but not always giving the impression of ‘being there’ with them. She puts this down to being ‘terribly inarticulate’, only being comfortable when she is putting sentences down in writing rather than in speaking. This comes across in most of the interviews featured in the book.

In her 1967 essay ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’, Didion famously wrote about the runaways and ‘hippies’ in the Haight-Ashbury area of San Francisco in the 1960s. Taking herself to live amongst them for an extended period in order to try to understand, a startling part of this essay appears when Didion ‘interviews’ a 5-year-old high on LSD (Didion’s own daughter was 2 years old at the time). In the 2017 Netflix documentary, The Centre Will Not Hold*, when asked about her feelings when discovering the 5-year-old drug addict, Didion’s face surprisingly lights up: ‘It was gold’, she states, ever the journalist, eager for the story.

(*Didion’s nephew, Griffin Dunne, made the documentary about Didion’s life; if you haven’t seen this, I would highly recommend it as a fascinating portrait of Didion’s life and writing, with up close and personal interviews with the writer and others).

Didion wrote iconic essays on the Patty Hearst trial and the Manson murders (which took place close to her own home) and tells of her meeting with Linda Kasabian and how she went out to buy her a dress for the Manson trial. She started work on a book about Kasabian, but this was later abandoned.

Didion was also involved in writing screenplays with her husband, John Dunne, something which she claimed was ‘…fun…It’s not like writing, it’s like doing something else’. These included Panic in Needle Park in 1971, and A Star is Born in 1976. Didion and Dunne both worked on their writing at home, and were one another’s editors. This worked for both of them, Didion says, with a mutual understanding that they would not always agree.

‘I did not always think he was right nor did he always think I was right but we were each the person the other trusted.’

Following the sudden and untimely death of her husband in 2003 whilst their daughter Quintana was recovering in hospital, Didion turned to a book of narrative non-fiction, publishing The Year of Magical Thinking. The book is a mediation on grief and the stories we tell ourselves in dealing with it, as well as a reflection of the couple’s marriage. The book was poignant in the way it deals with loss and grief, written in Didion’s precise, scalpel-like prose. It went on to win a National Book Award and was made into a one-woman stage play, with Didion played by Vanessa Redgrave.

‘Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.’

Further tragedy struck just two years later when, in 2005, Didion and Dunne’s daughter Quintana sadly died at the age of 39. Didion again turned to writing to try to understand her loss and the fact that she had to go on living without either her husband or daughter. The result was Blue Nights in 2011, another startlingly honest examination of love, loss and grief. What is remarkable about both these meditations on loss, however, is that one doesn’t come away from either of them feeling depressed. Didion’s writing style is so structured and precise that she manages to examine the deepest of human experience in a measured way.

‘Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it.’

New Journalism

Didion was a proponent of ‘New Journalism’, a style of news writing and prose journalism developed in the 1960s and ‘70s. It utilised literary techniques which were considered unconventional at the time. Characterised by a subjective viewpoint, it contained literary devices more known in long-form non-fiction, with the extensive use of imagery blended with the facts of news reporting. Whereas in traditional news journalism, the reporter is an invisible presence who merely reports on the facts. In New Journalism, the writer is immersed within the world of the story. Early proponents of this style of journalism were Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, and Hunter S Thompson, as well as Didion herself.

Much of this style of journalism was not found within traditional newspapers, but in magazines such as Harpers, The New Yorker, and Rolling Stone. Some criticism was levelled at this new style, as well as the writers of it themselves, including suggestions that the writers engaged more as sociologists or psychoanalysts. Some suggested that Didion wrote with a kind of existential ‘angst’, but she disputed this, claiming: ‘I’m really tired of this angst business. It seems to me I’m as lively and cheerful as the next person. I laugh, I smile…but I write down what I see’.

In a notorious 1980 essay ‘Joan Didion: Only Disconnect’, critic Barbara Grizzuti Harrison suggested that Didion’s writing was ‘a bag of tricks’ whose ‘subject is always herself’. Didion stated in a 2011 interview with New York magazine that Harrison’s criticism still raised her hackles even decades later.

As a writer, I am always interested in the way the writers I most admire work. In Didion’s essay entitled ‘Why I Write’ (1976), she points out that the structure of the sentence is essential to her work, advising: ‘To shift the structure of a sentence alters the meaning of that sentence, as definitely and inflexibly as the position of a camera alters the meaning of the object photographed’.

‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.’

She claimed amongst her writing inspirations Ernest Hemingway, whose writing taught her the importance of how sentences work in a text, and Henry James, who wrote ‘perfect, indirect, complicated sentences.’ She also stated, interestingly, that she believed we are most influenced by authors we read before the age of 20, as well as stating that she could not read much when she was working on a book. She surrounded herself instead with the facts and details of the place she was writing about, such as Central America whilst writing A Book of Common Prayer, and often returned to her family childhood home in Sacramento to finish a book, finding the peace and lack of belongings in her old bedroom a comfort and non-distraction.

Didion also indulged, as I know many writers do, in rituals to aid her creative process. On ending her day’s work, she would take a break from writing to remove herself from the ‘pages’, saying that without the distance, she could not make proper edits. She also did not review what she had written until the following day, sleeping in the same room as her work, citing this as one reason she liked to return to Sacramento to complete a book: ‘Somehow the book doesn't leave you when you're right next to it.’

In her essay ‘On Keeping a Notebook’ (1961), she reflects on the memories everyone holds; the things that remind them of special parts of their life. She amplifies writing down the things that happen directly to her or to a person around her, believing that writing down what is happening is a way to reconnect to a memory.

‘See enough and write it down.’

Didion’s last collection of essays was published in 2021, as Let Me Tell You What I Mean (BBC Sounds have an archive of this on audio that is well worth a listen, though sadly, not read by Didion herself).

Didion died from complications of Parkinson’s Disease at her home in Manhattan on December 23, 2021, at age 87, leaving a legacy of social commentary, enlightening fiction, and some of the clearest meditations on grief. This new collection of interviews with the writer gives an insight into her psyche, as well as just being an entertaining read. Her voice, as with the documentary, rings out strong and tenacious.

As a parting quote in her final interview, when asked what it meant to her to be defined as the voice of her generation, Didion responded: ‘I don’t have the slightest idea’.

After reading, I felt closer to understanding the way she lived and wrote, and the kind of person she was, making me want to return to her work and read every single thing she wrote, again and again.

Postscript: This is not an exhaustive list of ‘every single thing she wrote’, but is merely my recommendation on where to start if you haven’t read any Didion, or a reminder of some of her greatest work, and is based purely on my own choices!

Essay Collections:

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

The White Album

After Henry

(I was lucky enough to find this edition, Live and Learn, which features all three collections in one)*.

Fiction:

Play it as it Lays – the quintessential Didion-esque novel

Memoir/Narrative Non-fiction:

The Year of Magical Thinking - the best book on grief and marriage I have ever read

Joan Didion: The Last Interview and Other Conversations**

*All essay quotations refer to this edition

**All interview references relate to this edition

If you value the work that goes into writing this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber today. Your support makes this work possible.

I’m sorry to hear you are going through a difficult time, Kate. Sending you lots of very best wishes. And thank you for sharing one of your always excellent essays.

Kate, I am sorry to hear this wasn't a great week for you. However, Iam glad you pulled this out of the archives. Didion has been on my radar for awhile and this essay got me very intrigued. So well researched and written, your admiration of her is obvious!