Welcome to A Narrative of their Own, where I discuss the work of 20th century women writers and their relevance to contemporary culture.

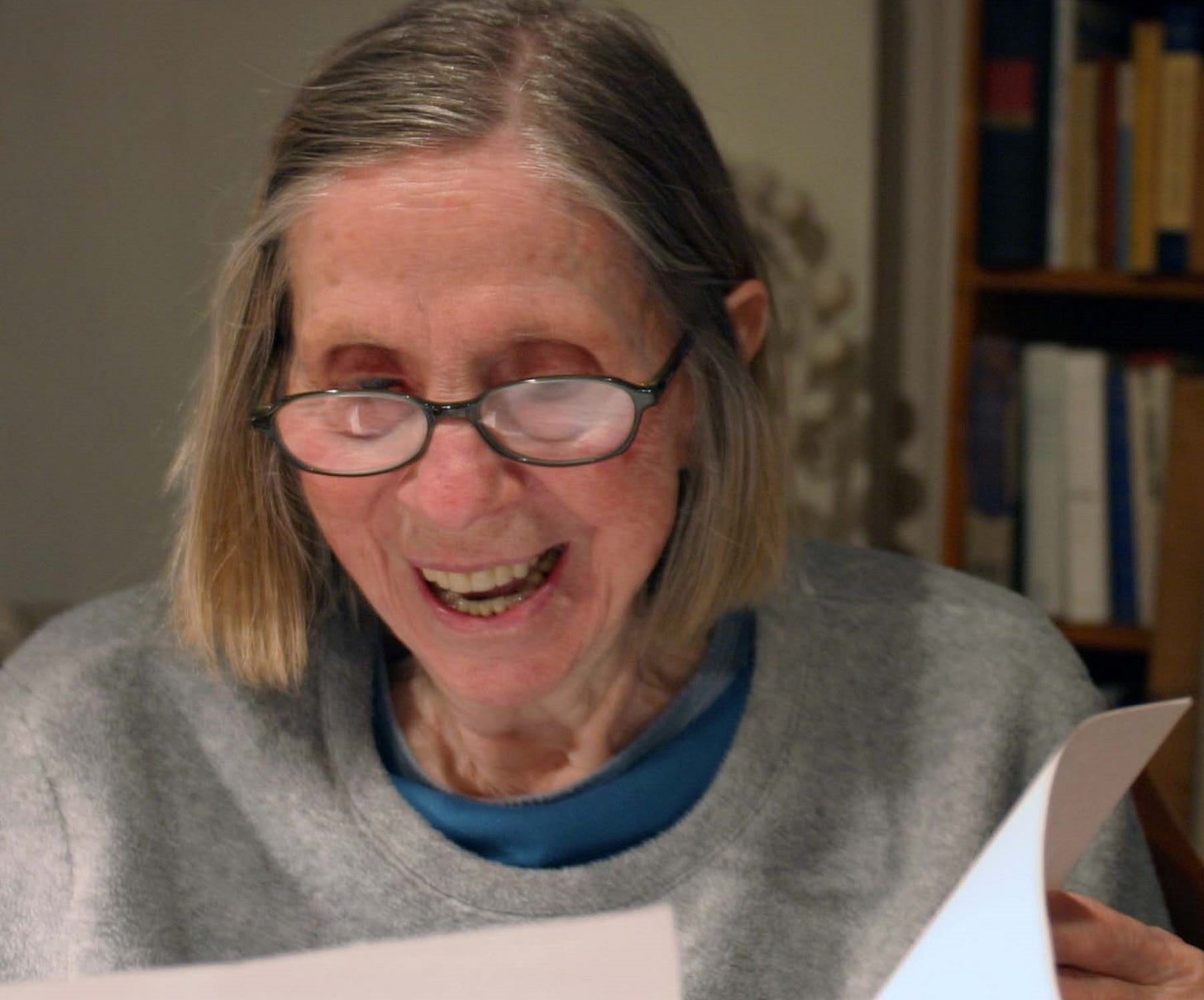

Last week, I looked at two poems by the 20th century modernist Barbara Guest: ‘The Location of Things’ and ‘The Brown Studio’. I had several comments from readers that they hadn’t come across her work before – which is why it’s such a privilege to research some of the wonderful 20th century women writers and to get the chance to introduce them to a new audience.

This week, I wanted to give a bit of background and context to Guest and her work.

Originally hailing from Wilmington, North Carolina, and born Barbara Pinson in September 1920, Barbara Guest grew up in California and attended both UCLA and the University of California, Berkeley. An early marriage in 1943 to English writer and translator Stephen Haden-Guest, in which the couple had one daughter, ended in divorce in 1954. Following this, it was writer friend Henry Miller who suggested to Guest that she try living in New York.

Guest had been interested in poetry in college, but this flourished when she moved to New York. Encountering the thriving art scene there, she later became a member of the prominent, informal group of writers known as the New York school of poets in the 1950s. Other members of the group included the poets Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and James Schuyler. Notably, Guest was the only female member of the original group.

‘I began to believe in my poetry, in its future’.

The New York school’s innovative poetry was heavily influenced by the modern art movement, in particular surrealism and abstract expressionism, although Guest claimed to be more influenced by other writers and poets than in painting.

The New York school’s poetry was serious yet often ironic in tone, and they often incorporated an urban sensibility within their work. Many of the members had affiliations with the modern artists of the era, such as Jackson Pollack and Willem DeKooning, as well as some members - such as O’Hara and Schuyler - working at the Museum of Modern Art, and others such as Ashbery writing for publications such as Art News.

Guest had also worked for the publication, and drew on her extensive art knowledge to create her lyrical poetry. Her first collection The Location of Things was published in 1960, and Guest claimed that her early love for the poems of Tennyson had led to her career as a poet.

‘[Guest’s poetry is] a tension-filled balance between a lyric, or purely musical, impulse; and a graphic or painterly impulse’.

Tyrus Miller, Contemporary Poets

Guest, however, was not to be pigeon-holed by her early work, becoming interested in the work of the language poets, whose interest focused on the words rather than imagery.

Language poetry was an avant-garde movement emerging in the late 1960s and early ‘70s as a response to the mainstream American poets. Taking its name from the magazine L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, it developed from a diverse range of poets from San Francisco and New York. Rather than working with traditional poetic techniques, the Language poets drew the attention to the use of the specific language within a poem which contributed to the meaning of it. It also placed importance onto the reader, allowing for their own construction of meaning.

In this way, some Language poetry intertwined with prose writing. Some of the major proponents of Language poetry were Michael Palmer, Lyn Hejinian, and Susan Howe, and their work is most often paired with that of deconstruction, poststructuralism, and objectivism.

‘My poems tend more to language than to ideas’.

Barbara Guest, American Poetry Review

Guest also had an interest in Imagism, which drew her to write a biography of Imagist poet Hilda Doolittle (known as H.D.), Herself Defined, in 1984. Imagist poetry developed following the end of WW1 and is less structured than earlier traditions. H.D. was seen as the original Imagist, and pioneered this type of poetry.

The writing of Herself Defined took Guest five years to complete, something which she later reflected on for her collection of poems Biography in 1981. Guest was said to be left with a distaste for biography following this experience, a theme which recurs in the collection. Often considered as containing Guests’ most accomplished poetry, her later collection Fair Realism was published in 1989.

As well as poetry and biography, Guest also wrote a novel Seeking Air in 1978. The novel, which has been described as a collage written in journal form, was said by Guest to be heavily influenced by Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage sequence. Guest adopted the stream of consciousness form of Richardson’s earlier novel, and even named her female protagonist ‘Miriam’ as in Richardson’s book. The novel broke with traditional narrative boundaries and form, leading some critics to label it ‘anti-narrative’.

Guest’s own critique of the narrative appears to chime well with her poetry style:

‘[it is an] account of what happens every day in New York City, and about Paris, and what somebody is thinking while looking out a window, and about memory, about the collusion of ideas, about coincidence, the brevity of ideas, about time, disorder, flux, etc’.

Losing her second husband—military historian Trumbell Higgins in 1970, with whom she had a second child, a son—Guest continued to write into old age, only stopping in her final year after a series of strokes. She died in February 2006 at the age of 85.

What I find remarkable about Guests’ poetry (and other writings) is that she refused to be labelled and appeared to be constantly evolving as a writer.

I think, both historically and contemporarily, we (both as consumers of art and art critics) often try to decode the work of writers and place them in a box. Guests’ work and her honest critiques of this show her willingness to be open to ideas and new forms. Spanning writing movements from Imagism, Language poetry, modernism, and structuralism – amongst others - she appears to have been constantly in flux, developing her own styles and responses to emerging artistic expression.

Similarly, her interest in other art forms led to her applying her writing to not just poetry but prose, novel writing, biography, and criticism. She left a legacy of writing behind, much of which was originally only available in pamphlet and journal form, but which was thankfully later placed into published collections and online editions, to be enjoyed for generations.

‘Stunning lyricism, her ability to leave everything out of a poem but the essential…the silences in Guest’s poems are as important as the sound.’

Robert Long, Southampton Press

Further Reading:

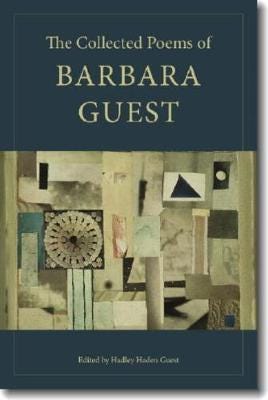

The Collected Poems of Barbara Guest contains all of Guest’s published poems, as well as a few previously unseen.

The Poetry Foundation has an audio of Guest’s poem ‘20’ on this link.

Poem Hunter also has links to many of Guests’ poems in written form on this link.

I adore HD, so this was especially interesting for me to read.