I recently read Tessa Hadley’s new book Free Love, a story featuring Phyllis, a suburban housewife in the 1960’s who takes the radical step of abandoning her family and running toward the promise of freedom in the exciting melting-pot of 1960s London.

The book begins with a seemingly satisfied Phyllis, mother of two and husband to Roger, a senior member of the Foreign Office; stiff-upper-lipped but a fairly decent bloke, living a comfortable existence in middle-class suburbia on the outskirts of London. However a visit from Nicky, the son of an old family friend of Rogers, and a stolen kiss in the darkness of the garden, sets Phyllis off on a path of self-discovery.

Seeking out the young Nicky and visiting him for steamy sex in his grotty flat in up-and-coming Ladbroke Grove leads Phyllis to question everything she thought she knew about the bourgeois lifestyle she has been living, as she increasingly gets enticed into the pot-smoking, artistic, and rebellious existence of the swinging ‘60s culture of London.

Hadley expertly assesses what it means to find oneself amidst the revolution and whether a woman approaching 40 can really pull off leaving everything she knew behind (including her two children) and make a new life for herself. Their youngest child Hugh, aged 9, is about to be sent off to boarding school - something she disapproves of - and her increasingly disenfranchised teenage daughter Collette attends a private day-school, where she is about to take her A levels.

Hadley’s portrayal of the unfaithful Phyllis is interesting: she neither vilifies her for running away, nor glamorizes her new lifestyle. Instead, Hadley’s narrative allows the reader to develop their own feelings for Phyllis and the other characters. Though Phyllis is shown undergoing her own private sexual revolution, Hadley’s portrayal is not to make everything in the revolution’s garden rosy.

She also interestingly introduces Phyllis to neighbours of different races and class to anyone she has come across before, and in this way, makes Phyllis a more rounded and empathetic character that I couldn’t help but warm to, whilst simultaneously finding her total abandonment of her children difficult to understand.

‘She saw how fatally Roger and the children held her fixed inside their shape, so that she couldn’t change her own life without bringing everyone else’s down around her’.

Hadley also allows for some empathy of Roger’s character by introducing his own latent desires for an old friend, and I think in this she attempts to show that it is not only women who struggled with the status quo of the expectations of gender in quiet, 1960s upper-middle-class suburbia.

One of the highlights of Hadley’s narrative is Grenadian trainee nurse and neighbour in Ladbroke Grove, Barbara Jones. She adds a streak of ironic straight-talk to Phyllis’s often idealistic view of life on the fringes, with her ambitions to better herself despite the working-class, discriminatory landscape she finds herself in. This allows for some expansion on the novels otherwise predominantly white middle-class feminism.

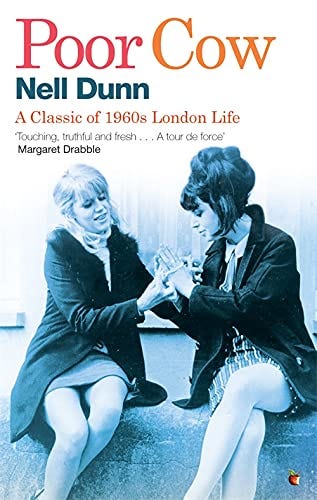

I was interested to compare Hadley’s novel with another novel set (and written) in the same era of 1960s London, Nell Dunn’s Poor Cow. Dunn’s novel appeared in 1967, causing scandal with its openly explicit frankness about female desire and unsentimental portrayal of central character Joy.

Set in 1960s Fulham, at the time an area of yellow-brick terraces belonging to predominately working-class renters, the novel opens with Joy taking her new-born son to a café.

‘She walked down Fulham Broadway past a shop hung about with cheap underwear, the week-old baby clutched in her arms, his face brick red against his new white bonnet’.

Britannia Road, situated just down the road from Fulham Broadway, lies on the boundary between the fashionable swinging Chelsea and its poorer neighbour Fulham. The contrast between the two are evidenced in the novel, with Joy shopping for cheap fashion from the local market, rather than the fashionable King’s Road boutiques.

Joy is 22 and married to Tom, a thief who has been sent to prison, forcing Joy to move into her aunts one-room dwelling. She begins a relationship with Davey, a friend of her ex-partner, eventually moving into a council flat with him. After an abusive and controlling relationship with Tom, Joy is happy in her new relationship with Davey, who is a kind and warm boyfriend, though still a thief like Tom. After a burglary goes wrong, Davey is also sent to prison and Joy is forced back to her aunt’s house.

Taking a job as a barmaid, she befriends a colleague, Beryl, and gets on well with the local punters. She enjoys sexual relationships with several of these, as well as posing as a glamour model for extra cash. When Tom leaves prison however and takes her and her son to Catford, she falls pregnant again and their abusive relationship continues, with Joy feeling unable to leave the marriage due to her children. Her lack of agency is palpable, with the limited choices this brings.

‘I don’t want to be down and out all the time…’

The narrative is shaped around Joy’s voice and uneducated position, with the letters she writes to Davy in prison full of spelling errors and it’s difficult not to see Dunn as a little patronizing in the way she portrays the plight of the working-class Joy.

A wealthy upper-class woman, Dunn left her own comfortable existence to live amongst the working classes and wrote about them in several novels and her famous short-story collection, Up The Junction. Her business owner father, however, did not feel that women needed education, and Dunn was quoted as responding to criticism of Joy’s uneducated letters to Davey by stating that she could not spell much better than Joy, and was not very educated herself.

Dunn was brought up in Chelsea and married another writer, Jeremy Sandford. The pair moved to the less desirable area of Battersea and brought up their three sons, a place which provided material for both writers (Sandford wrote the script for the groundbreaking film Cathy Come Home), with director Ken Loach being a frequent visitor, leading to the film production of Poor Cow.

Dunn also immersed herself in the scene by taking a job in a sweet factory in order to assimilate into her surroundings. Here she met Josie, a worker who inspired the character of Joy, and the pair became close friends. Arguably, Dunn’s personal circumstances allowed for her to live amongst working-class people and utilize them within her fiction in a way that feels a little voyeuristic. She has however indicated in interviews that she found friendship in the communities she encountered in Battersea that she couldn’t get from the people from her aristocratic background. This brought her a sense of liberation.

Dunn’s portrayal of Joy shows a character who presents with little regard for how her life is going or with any sense that she may be able to take agency within in. Frustratingly, she appears resigned to the misfortunes of her life. She does not seem to have any remorse for living on the rewards of crime, nor wish to better her circumstances by working. Her feelings towards her son tend between an initial ambivalence to a close affection as the novel develops.

‘Even when she wasn’t with him, she could feel his weight in her arms and his mouth, after drinking, wet against her cheek…all that really matters was that the child should be all right and that they should be together’.

Dunn’s depiction of working-class life in 1960s London evokes a city coming to terms with the austerity of the 1950s, with factory jobs in plentiful supply. Dunn found a sense of freedom within the streets of Battersea where she chose to locate with her young family; somewhere she could absorb the realities of the time perhaps, regardless of whether you agree with her methods. She claimed to remain good friends with Josie the former barmaid. However, unlike Josie and the others, it must be remembered that she could leave her situation at any time she wanted, and did in fact leave Battersea for Fulham eventually.

Similarly, in Hadley’s Free Love, we are told early on that Phyllis has a small amount of savings, as well as being able to rely on her husband’s wealth and capability of taking care of matters at home. Although she may feel claustrophobic in her middle-class suburban existence, she nevertheless has the financial means and agency afforded a woman of her class and education to leave her husband and knows that their children will be taken care of.

Some critics have cited Hadley’s resolution of Phyllis’s story underwhelming, and if I was to offer any personal criticism, I would say that the story does seem to peter out a little towards the end. The latter part tends to bring Phyllis’s daughter Collette into more of the narrative, and I can see that Hadley’s reasoning behind this may have been to portray the new generation moving into this new world of possibilities and sexual freedom.

However, it was Phyllis’s story I was most interested in, and in this, I would say that Hadley’s ending is a realistic and quiet resolution to Phyllis’s mid-life bildungsroman.

Postscript: If you enjoyed this post, why not consider a free or paid subscription to A Narrative of their Own? Free subscribers receive weekly newsletters on 20th century women’s literature and contemporary discussions around them, as well as a monthly roundup of other great writing. Paying subscribers also receive a bi-weekly special edition deep-dive, as well as supporting my ongoing research.

An interesting read Kate, thank you. My book wish list is increasing with each of your newsletters.

This really resonated with me. Another fantastic piece