Do you value the work that goes into writing this newsletter? Consider becoming a paid subscriber today. Your support makes this work possible.

I wrote last week about re-reading. In the comments to that post, some interesting ideas surfaced around the reasons and seasons of our lives when we might pick up a book we have read before. I mentioned to a reader that I often re-read a book for a couple of distinct reasons. One is if I want to write about the book, the author, or research into the themes covered in the text.

The other is simply that it remains in my mind as a book I loved the first time around; a comfort read that I just want to lose myself in again and again. It feels like the characters are close friends that I want to check back in with.

Do you get this?

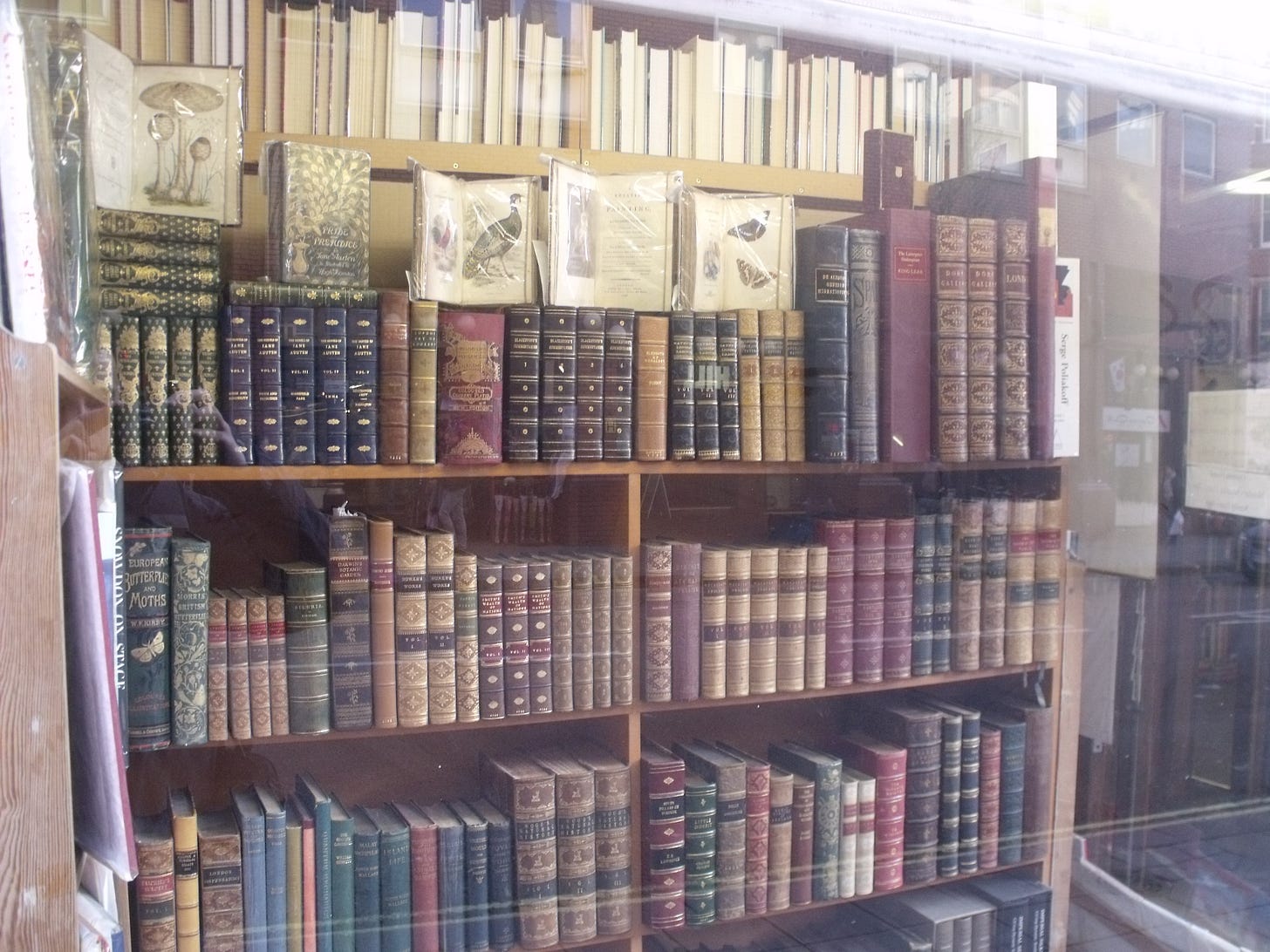

I have several of these books, and usually indulge in a re-read around the winter holidays, in particular, or anytime I’m ‘between books’. One such book is Helene Hanff’s 84 Charing Cross Road.

In this slim book, which is really more of a novella in length, the real-life story of Hanff’s friendship with British bookseller Frank Doel is revealed through the letters they exchanged over two decades, beginning in 1949.

Helene Hanff was a script reader and occasional script writer (and later television writer for the series The Adventures of Ellery Queen) based in Manhattan, New York. She initially pens a letter to the London booksellers Marks and Co, requesting a book:

October 5th, 1949

“Gentlemen:

Your ad in the Saturday Review of Literature says that you specialize in out-of-print books”.

She receives a polite but unemotional response from bookseller ‘FPD’ informing her that:

25th October 1949

“Dear Madam,

In reply to your letter of October 5th, we have managed to clear up two thirds of your problem.”

The letters are initially signed off “FPD, For Marks and Co”, but later, after some teasing by Helene, become “Yours faithfully, Frank Doel, For Marks and Co.”

This brief communication between the two begins a 20 year correspondence which expands outwards from not just Helene and Frank’s letters, but into other members of the staff of Marks and Co, and even Frank’s second wife, Nora.

If this sounds like something of a slight storyline, let me try to convince you that it holds so much more. Not just a story of a long-distance friendship, but a love letter to English literature, and a window on the cultural landscape of the era.

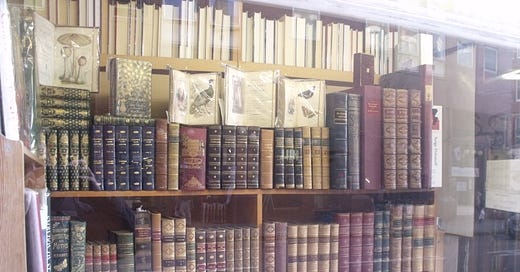

Throughout the years of Frank and Helene’s correspondence, historical events and changes for life in both Britain and the US are revealed. In particular, as the letters begin in 1949, we see a British public still experiencing food rationing following the end of WWII. When Helene becomes aware of the shortages of meat and other products for the approaching Christmas celebrations, she touchingly arranges for a parcel of food to be shipped to the bookshop from a company in Denmark, care of Frank, which he dutifully shares out between the staff members.

Helene is merely responding in kind to what she sees as a remarkable service the bookshop provides in sourcing the books she requests and which she struggles to find in the US. A lover of English writers and writing, she is astounded at the low prices of some beautifully bound editions, which she cannot source at home.

Although Helene is a lover of literature, she admits to not having a college education, and her own career has not thus far been altogether successful. We see that she lives alone in a one-room apartment, reading scripts and writing the occasional one, which never gets produced. She is not a wealthy woman. In fact, what she really wants to do more than anything is to come to London and visit the sites of the literature she so loves. But she keeps getting thwarted by her financial struggles, and trips come and go unfulfilled. A particularly disappointing point comes when Helene plans to visit with her savings from her new role as script-writer for Ellery Queen in time for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, only to be disappointed when she needs extensive dental work. The struggle for a single woman as a working writer is evident.

The relationship that builds between Helene and Frank is interesting; it is purely platonic, but they share a love of great literature and a sense of humour. Helene’s character flows from the letters: she is a brash New Yorker, a chain-smoking writer, and often chides Frank, amusingly, for his lack of urgency and typically British, stand-offish manner.

“Frank Doel, what are you DOING over there, you are not doing ANYthing, you are just sitting AROUND.”

Frank, meanwhile, initially appears in the letters as a predictably stuffy Brit. His missives are polite and solicitous, initially addressed “Dear Miss Hanff”.

As the correspondence progresses, however, and the whole staff of Marks and Co begin sending their own letters of thanks to Helene for the care packages, there is a real sense of him beginning to unwind, with the letters turning to “Dear Helene” and being signed off “Faithfully yours, Frank”, or “Love from us all”.

What is so nice about the book is the effect that Helene has on all the Marks and Co staff (and they on her). Not just with her gifts, but the way in which her letters bring them together in a time of hardship following the war. Frank’s references to the death of the King, as well as one of their staff members, and the coronation of the new Queen Elizabeth are also significant points in the narrative.

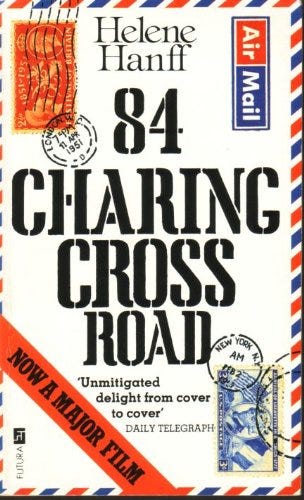

As well as the book, I also highly recommend the 1987 film version starring Anne Bancroft as Helene and Anthony Hopkins as Frank. Both are impeccable in their performances, and I can’t think of any two actors who could bring the story to life better. In fact, in something that sounds like a novel itself, Anne Bancroft told the Los Angeles Times on release of the film that she was approached by a member of the public whilst on the beach at Fire Island, New York, who passed her the book and asked if she’d read it. He then pointed out that she would be great for the part of Helene. Bancroft (who was also brilliant as the infamous Mrs Robinson in the film version of The Graduate) had not read the book, but once she did, she agreed.

‘“Do you know this book?” he asked. “You should read it. You’d be great for it.” The book was Helene Hanff’s “84 Charing Cross Road.”’ Anne Bancroft in Los Angeles Times

Bancroft and husband Mel Brooks then set about acquiring the film rights, and eventually got the film produced in 1987. It had been a hard sell, being a book essentially about a twenty-year friendship set around literature and told through letters. But Bancroft is perfect as the chain-smoking New Yorker, frustrated by her lack of money from her writing, but loved by her friends and neighbours. A particularly amusing scene shows Helene presenting a huge Yorkshire pudding she has baked (on the instructions of Marks and Co staff) in honour of her British neighbour Brian, who often helps her translate the cost of Marks and Co books from British pounds and shillings to dollars and cents.

I wasn’t sure how it would stay true to a book that is told in letters, but it manages it perfectly, flipping between Helene and Frank’s worlds and their intersections, with the occasional breaking of the fourth wall as Helene “speaks” to Frank via the audience.

In the book edition that I have, a second novella features called The Duchess of Bloomsbury, in which we see Helene finally make the trip to London, ironically following the British publication of 84 Charing Cross Road. This time, the narrative is not told in letters but in diary form, where Helene details her arrival in London following a recent hysterectomy, accompanied by her customary ironic humour. There, she meets various people, some connected to Marks and Co and some not, who kindly escort her around the literary London she has always dreamed of seeing.

Despite a life-long love of great literature, Helene Hanff’s own career path was not altogether successful. Prior to the release of 84 Charing Cross Road, Hanff had been eking out a living as a script reader for Paramount Pictures, whilst writing plays that never got produced. She also wrote articles for encyclopaedias and children’s history books, and later the Ellery Queen scripts for television.

On hearing of the death of Frank Doel and realising that the correspondence between both them and the bookshop over twenty years was effectively over, Helene Hanff found herself on the point of despair. In both her career and her life, she felt a real sense of loss.

"I was a failed playwright. I was no-where. I was nothing." Helene Hanff in The Independent

She decided that the only thing she could do to deal with her grief was to put the letters into a story to honour her relationship with both Frank and Marks and Co.

First published in 1970, the book was a huge success, gaining something of a cult following, surprising the typically self-deprecating Hanff, who referred to it as:

“My little nothing book; I thought I was writing a New Yorker story when I wrote it. I still think it is a nice little short story." Helene Hanff in The Independent

In 1980, the book was turned into a stage play, first appearing on the West End and later, Broadway. In 1987, the film version appeared.

It was the publication of the book by British publishers Andre Deutsh which brought her to England for the first time. This visit, and subsequent others, led her to write the sequel which appears in my copy, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street in 1976.

Regular talks on BBC Radio Four’s Woman’s Hour entitled “Letter from New York” and two further books followed: The Apple of my Eye, a quirky look at New York in 1978 and Q’s Legacy in 1986, about the work of Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, the man who first lit her passion for English literature after discovering his essays in a library. These efforts combined to finally allow her to make some money from her writing.

Hanff preferred reading real-life literature to fiction, and this is what her own books were about. Ironically, she never made money from her first love of script writing; the only script that made it to the stage being the adaptation of her book, 84 Charing Cross Road.

In honour of the book that eventually made her name, a plaque is now placed on the site of the former Marks and Co bookshop reading:

“84 Charing Cross Road

The Booksellers Marks and Co

Were on this site which became world renowned

Through the book by Helene Hanff.”

If you have never read the book, or seen the film, I implore you to do so. It is such a slim novel, easily read over a weekend. It leaves you with a sense of nostalgia for the lost art of letter writing, and is a feel-good novel dedicated to the shared love of literature.

I have recently reduced my paid tiers to allow for all budgets who would like to support the work I do here, uncovering the narratives of women. Paid subscriptions help me to continue to write and research quality newsletters every week - and the yearly fee works out at less than £2 per month! Thank you for reading 😀

![84 Charing Cross Road [DVD] (1986) Anthony Hopkins Anne Bancroft - Picture 1 of 1 84 Charing Cross Road [DVD] (1986) Anthony Hopkins Anne Bancroft - Picture 1 of 1](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xdQG!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F86a1fa4f-45e2-4067-999c-d1601d356f05_1096x1600.jpeg)

Thank you for this. I hadn’t thought about the book (and the movie) in quite some time. My daughter is in her first semester in college and loves reading. I just sent her a copy.

What a delightful little book! I recognize the name but cannot remember having read it, so off to the library I go.